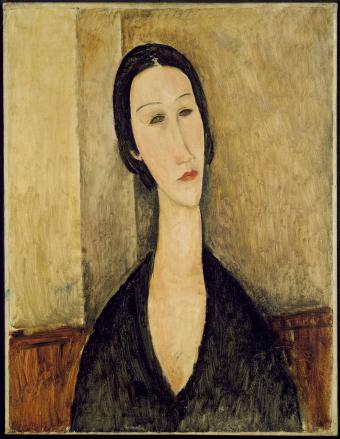

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — To the causal observer, the painting is most striking in its simplicity: a two-dimensional image of a woman, her face elongated, head slightly tilted, the background giving away little of her surroundings, the parameters devoid of a signature identifiying the artist.

It’s a painting that senior Annika Finne has come to know intimately. The aspiring art conservator has spent the last year investigating the authenticity of the painting for her senior thesis. Her research has revealed that the painting carries with it a history far richer than its outwardly simple appearance. Through an analysis that took her to museums around the country, diving deep into provenance files and performing a battery of scientific tests, Finne was able to prove that the painting, an oil sketch titled Portrait of Anna Zborowska, is quite likely the work of one of the best-known artists of his time: Amedeo Modigliani.

The painting spent the last 64 years in storage in the archives of the RISD Museum of Art. It was donated to the museum in 1933 and initially displayed as a Modigliani. But certain events led curators to begin to question its authenticity, according to Finne. Tucked into the painting’s file at the museum is a letter to curators from Alfred Barr, one of the founders of the Museum of Modern Art in New York and a heavyweight in the art world. Dated June 12, 1951, the letter describes the painting as “weak” and likely not authentic.

The simplicity of Modigliani’s works, combined with the artist’s prolific creation during his lifetime, made him easy to knock off. Additionally, Modigliani often painted the same subject several times, so adding a forgery to a series without notice was not difficult to do. These factors led to a market ripe for forgeries - and plenty of skepticism over seemingly authentic pieces - in the 1940s and 1950s, prompting RISD to eventually put Portrait of Anna Zborowska into the archives until further investigating could be done.

Fast-forward more than six decades, when Finne was working in the museum as part of her independent concentration in material art history, overseen by Evelyn Lincoln, associate professor of art history and architecture. Looking for a piece of art to investigate for her thesis, Finne consulted with Ingrid Neuman, objects conservator at the museum. “The museum is full of objects that just need somebody to look at them really carefully and investigate them. It’s so full of opportunities,” Finne said. Neuman put her in touch with Maureen O’Brien, curator of paintings and sculpture, who had just the project in mind.

Finne began by looking into the painting’s file for any evidence directly linking Modigliani and Portrait of Anna Zborowska. Modigliani, who died in 1920, left many of his works to his primary art dealer at the time, Leopold Zborowski, also the husband of the painting’s subject. Finne knew that in order to prove its authenticity, she would need to trace the painting’s route from the artist’s Paris studio at the time of his death, to 1933 when it was donated to the RISD Museum of Art. She was able to find proof that Leopold sold the painting to the person who donated it to RISD, but conclusive evidence that the painting was in Modigliani’s studio at the time of his death was harder to come by. So she started looking at other Modigliani portraits that Leopold sold at that time, checking to see if they bore any similarity to the one in question. In the Frick Collection archives she found evidence that Leopold had sold a similar unsigned oil painting that is accepted as an authentic Modigliani to a third party named Abby Rockefeller.

The other part of Finne’s investigation focused on the physical aspects of the painting. Traveling to several museums around the country last summer, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., Finne examined other authenticated Modigliani works. “I was basically building a stock of evidence of authenticated paintings that I could then use for comparison,” Finne said. She took detailed photographs, noting the thickness of the paint applications, as well as any evidence they had on file that confirmed Modigliani as the painter.

A turning point in the investigation was initially thought to be a setback. An installation photograph from the 1930 Venice Bienalle, featured in a catalogue published by the Jewish Museum in New York, identified a painting as Portrait of Anna Zborowska, which would make the painting’s trek to RISD even more obscure than originally thought. But closer examination revealed that it wasn’t the same painting, just an extremely similar version. Delving deeper into Modigliani’s work patterns she realized that the striking similarities made sense. “Modigliani habitually made multiple versions of the same image and often some of those iterations were these oil sketches. There were many other paintings like this that were also really thin and unsigned and they had corresponding paintings that were finished.” Her finding was another piece of evidence connecting painter to painting.

The final piece of the puzzle was a scientific analysis, performed at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. The goal was to discern the types of pigments used in the paint, but infrared reflectography revealed an even bigger find: a pencil underdrawing around the face and background. “That was so exciting to see,” said Finne, who described the lines in the drawing as “incredibly light but very confident.”

Finne compared the underdrawing to those found on authenticated Modigliani portraits as well as finished drawings by the artist. “You could see these habitual mark-making flourishes under the lips and the way he would note how the angle of the head was tilted. Those similarities and processes are a particularly powerful argument for determining the authenticity of a painting because it’s something you can only know by doing these sorts of analyses. If you were a forger, you could look at the paintings but couldn’t get the sort of information that was evident. Knowledge of process is much harder to come by than knowledge of appearance.”

In February, Finne presented her body of research to her thesis committee, which included her adviser, Lincoln, as well as Neuman and O’Brien of RISD. All three felt the evidence was strong enough to take it to the next step in the authentication process. “The Museum would like to share Annika’s research with the specialists on the Modigliani catalogue raisonné committee. We are hopeful that this will lead to a firm establishment of the painting’s authenticity and that it will eventually be returned to view,” O’Brien said.

Finne is also hopeful, not only because reintroducing the painting to public display would be the ultimate affirmation of all of her hard work, but because she thinks future art students would benefit. “Having this painting is particularly significant because it is a process painting. For a museum geared toward the education of artists, it’s particularly important to have these process works, to show Modigliani’s process. I think it could occupy a particularly significant role in collection.”

As Finne continues to work toward her goal of becoming an art conservator, her concentration adviser said she’s already made great strides in the field. “One of the questions we put to Annika was, ‘What does it mean to our idea of Modigliani’s work to exhibit a clearly unfinished oil sketch? Should we do that?’ I was thrilled with the clarity and sophistication of the way she addressed that question, making it specific to the place (the RISD Museum) and arguing that the picture, along with her work on it, offered much to educated artists and art historians, while also making it obvious to other viewers that process was an important aspect of an artist’s work.”

For her part, Finne says she’s grateful for the insight this investigation has given her. “I’ve come to see authenticity investigation as this really valuable exercise, because when you question of whether something is genuine, you really get at the heart of why we place value or significance on any work of art. It was really wonderful to go through that process, because it clarified what I find significant in paintings and why I want to go into conservation.”

This fall, she’ll continue on that path, with some real-world experience under her belt. She will enter the New York University Institute of Fine Art Conservation Center in the fall, where in four years she will earn a master’s in art history and an advanced certificate in conservation.