PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — People are free to switch between traditional, public Medicare and private Medicare Advantage plans every year. Under normal circumstances that traffic is equal in either direction — that is, a new Brown University study shows, until more costly services, such as hospital, at-home or nursing home care, become necessary. Then, despite federal policy to prevent this, the migration becomes decidedly away from the private plans toward the public one.

"Our results raise questions about whether current Medicare Advantage regulations and payment formulas are designed to meet the needs of Medicare Advantage members who use post-acute and long-term care,” wrote Momotazur Rahman, assistant professor (research) of health services, policy and practice in the Brown University School of Public Health, and colleagues in the October issue of the journal Health Affairs. “The unidirectional flow of these high-risk and often high-spending patients from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare appears to transfer responsibility to traditional Medicare just as patients enter a period of intensive health care needs.”

“As the intensity of care use increases, the likelihood of switching out [of Medicare Advantage] also increases.”

Medicare Advantage plans have financial incentives to enroll and retain only the healthiest, lowest-cost patients. To encourage them to take higher-cost ones, Congress in 2003 passed a law to pay the plans at an enhanced rate based on the risk level of their patient population. Ever since, while there was a rapid growth in enrollment in Medicare Advantage, researchers have debated whether the enhanced payment has encouraged Medicare Advantage to serve higher-cost patients.

The new study provides evidence that at the time some patients become more costly, they also find Medicare Advantage no longer meets their needs. Rahman and his colleagues found that evidence by combing through the Medicare enrollment and services usage records of more than 36 million people between 2010 and 2011.

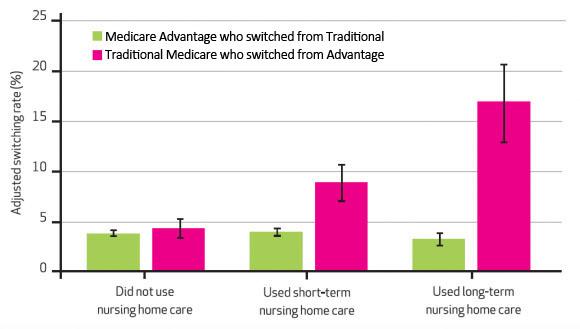

Between those two years the switching rate from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare was higher than from traditional to advantage for people who used long-term nursing home care (17% vs. 3%), short-term nursing home care (9% vs. 4%), home health care (8% vs. 3%) and acute hospital care (5.3% vs. 3.4%). These were all statistically significant differences.

Meanwhile, among people who did not have any of those needs, there was no statistically significant difference in switching rates from one kind of Medicare to the other.

Rahman said the case of institutional nursing home care is especially interesting because plans are paid at an adjusted rate for enrollees needing that service and yet these enrollees were more likely to leave Medicare Advantage.

“As the intensity of care use increases, the likelihood of switching out also increases,” he noted.

The asymmetry of switching rates was even greater among patients who are dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare. They are a notable group, in that unlike non-Medicaid patients, they can switch anytime rather than having to wait for an annual enrollment period.

While the study documents a significant degree of switching out of for-profit plans at a time of higher costs, it does not show why the switching occurs. It could be the plans’ benefit structures, their cost sharing requirements for certain services, the ease of accessing benefits, or some other aspect of how that care is administered through the plan or by hospitals and nursing homes.

“We just discovered a basic pattern and that leaves us with many unresolved questions,” Rahman said. “They clearly have some dissatisfaction with the care they received, for which they disenrolled the next year.”

That dissatisfaction, whatever its origin, is apparently sufficient for people to incur the inconvenience of leaving a plan they had chosen.

To avoid that, Rahman said, “patients with high care requirements need to choose Medicare Advantage plans carefully using quality measures published by CMS, especially the one based on enrollees’ satisfaction.”

In addition to Rahman, the paper’s other authors are Laura Keohane, Dr. Amal Trivedi, and Vincent Mor.

The National Institute on Aging funded the study (grants: R01AG047180-01, R01AG044374-01, P01AG027296).