PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Millions of seniors with Medicare Advantage plans, including more than a million with low incomes, were on the hook to have large out-of-pocket costs for a 27-day course of hospital and skilled nursing care, according to a new study.

“Policymakers are very concerned about how much Medicare beneficiaries need to spend for essential medical services,” said Dr. Amal Trivedi, associate professor of public health at Brown University and corresponding author of a new study in the June issue of the journal Health Affairs. “It’s one of the goals of insurance — to protect people from large, catastrophic out-of-pocket expenses.”

Copays, or cost-sharing, can limit health care usage if the high out-of-pocket costs they engender discourage consumers from engaging certain services. In the new study the researchers focused on a sequence of services that is medically important, difficult to predict, expensive, and common.

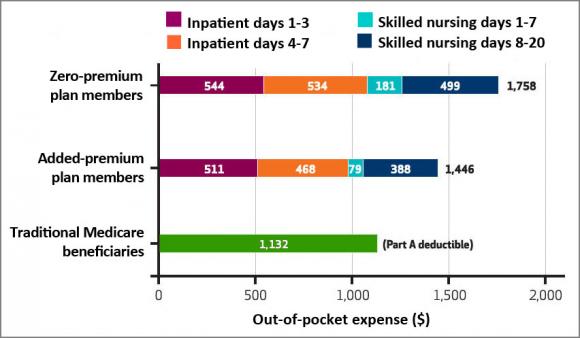

What the data showed is that on average in 2011, seniors in Medicare Advantage plans that had lower premiums were expected to pay $1,785 for a week in the hospital and 20 days in skilled nursing, which are typical stays in the aftermath of catastrophic incidents such as stroke, congestive heart failure, or a hip fracture, Trivedi said. People in plans with higher premiums faced an average copay of $1,446.

Medicare Advantage copays were just as high for members who receive federal subsidies because their incomes are between the poverty level and 150 percent of poverty, added study lead author and Brown doctoral student Laura Keohane.

“For low-income beneficiaries, these copayments for inpatient and skilled nursing care could be more than a month’s worth of income,” Keohane said.

Seniors with traditional Medicare would pay a $1,132 for a week in the hospital and 20 days in skilled nursing, plus additional copayments for physician services while hospitalized.

“The perception out there is that Medicare Advantage offers more generous benefits than traditional Medicare without supplemental coverage but for long inpatient stays and long stays in a skilled nursing facility, that’s generally not the case, we found,” Trivedi said.

For shorter stays in the hospital and in skilled nursing facilities, Medicare Advantage copays were lower than those of traditional Medicare. Because many Medicare Advantage plan copays rise with the length of hospital or skilled nursing stays, the average costs for only three days in the hospital were $544 for low-premium plans and $511 for those with higher premiums.

Despite policy protections

Keohane, Trivedi, and their co-authors considered the issue in the context of federal policy changes starting in 2011. In that year, federal officials restricted some cost-sharing levels and imposed a cap of $6,700 on total out-of-pocket costs and restrictions on copays in Medicare Advantage plans, with the intention of protecting consumers. Some plans already offered members a cost sharing limit at an allowed level, but others did not. Under the new regulations, Medicare Advantage plans that agreed to a lower cap of $3,400 could gain more leeway regarding how they could revamp their cost-sharing. Traditional Medicare has no cap on out-of-pocket expenses.

To conduct their study, the authors looked at the anonymized records of more than 8 million Medicare Advantage enrollees and the pricing structures of their plans, both before and after the federal policy changes. The seniors were enrolled in 1,841 Medicare Advantage plans, including 333 specialized plans.

The researchers’ analysis calculated what average customers were expected to pay for hospital and skilled nursing care based on their plan terms and whether they received subsidies, for instance for Part D drug coverage, because of low income. One set of findings were the Medicare Advantage costs and how they compared to traditional Medicare. But the researchers also examined the specific impact of the 2011 policy changes.

That analysis showed that among Medicare Advantage members in low premium plans that already had an out-of-pocket limit, fewer than a third of members had increased copays for hospital or skilled nursing care after the policy change and more than a third of members had a reduction in copays. But among those members for whom the out-of-pocket caps were new, 55 percent had increased copayments for hospital stays and 46 percent had greater copays for skilled nursing. Fewer than one in six of members in plans with new out-of-pocket limits had lower cost-sharing.

The study data suggest that imposing an overall cap on out-of-pocket costs may have resulted in many plans increasing copays for hospital and skilled nursing care, but it does not explain why. To finance the expense of adding an out-of-pocket limit, Medicare Advantage plans may have raised copays.

Trivedi and Keohane hypothesize that greater copayments for hospital and skilled nursing care may dissuade people who are more sick (and more expensive to cover) from enrolling in some Medicare Advantage plans or cause those receiving these services to exit their plan. No one can predict a catastrophic need for hospitalization, but a sicker person may be more likely to be deterred from a plan with higher copays for such care.

Ultimately the authors said they hope policymakers will look at whether more needs to be done to protect Medicare Advantage consumers, particularly ones with low incomes, from high out-of-pocket costs for unpredictable catastrophic illnesses such as the ones that result in long hospital and skilled nursing stays.

In addition to Keohane and Trivedi, the paper’s other authors are Regina Grebla and Vincent Mor.

The National Institute on Aging funded the study (grants P01AG027296, R01AG044374).