PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — After the near-disaster of Apollo 13, NASA’s lunar exploration program stood at a crossroads. President Kennedy’s goal of landing a man on the Moon and returning him to Earth had been achieved, and many wondered, given the dangers, if it might be time to scrap Apollo.

But at that point, “NASA management made a bold decision,” said Apollo 15 commander David R. Scott, who spoke last week to students in Professor Jim Head’s Geology 50 classes. “Rather than abandon Apollo, let’s expand it.”

NASA managers decided to double the scientific capacity of the remaining lunar missions starting with Apollo 15. That first expanded mission would be “arguably the most productive science exploration mission away from the Earth,” Head told his students.

Scott and Head, professor of geological sciences, believe that the synergy between scientists and engineers that made Apollo 15 so productive should be the template for future human exploration of planetary bodies. “You are the ones who are going to go on these missions,” Head told his students in his introduction of Scott. “So pay close attention. Here’s your roadmap.”

Scott’s visit last week was a continuation of a long relationship between the astronaut, Head, and Brown. Scott, now a visiting professor of geological sciences at Brown, has been coming to Brown for more than 30 years to share his experience and expertise with students. He first met Head in 1968, when Head worked with NASA to train the Apollo astronauts on the geology of the Moon. The two have worked together ever since.

“Dave has a voracious appetite for learning and he loves geology,” Head said in an interview. “He was exceptional on the Moon, and the scientific return from that mission was amazing.”

A productive mission

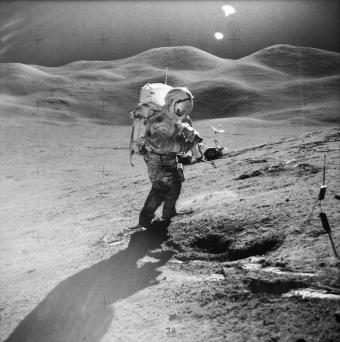

Expanding Apollo 15’s science mission meant building more time into the mission plan for geological exploration, making room for a larger payload of lunar samples, and using a rover to traverse greater distances on the lunar surface. It also meant changing landing procedures to make a more complicated landing in the Hadley-Apennine region, a geological hotspot (and a site Head was instrumental in choosing).

Achieving new science goals required substantial changes from previous mission plans. They were achieved through what Scott refers to as “science-engineering synergism.”

“The geologists and scientists worked together with engineers and managers to optimize the program,” Scott said. “It’s the kind of thing Jim and I are trying to emphasize ... so that the science community understands the engineering and the engineers understand the science. Working together, we get better science and better engineering.”

On Apollo 15, the result of that synergism was an unprecedented geological exploration of the Moon.

The scientific return from the mission included the “Genesis rock,” a chunk of anorthosite over 4 billion years old thought to have been part of the Moon’s original crust. The astronauts also returned a clump of sediment containing tiny green volcanic beads. More than 40 years later, Brown geologist Alberto Saal found evidence of water in those beads — definitive proof that the Moon’s interior contains a similar proportion of water to that of the Earth. Last year, Saal used those same samples to show that water inside the Moon and Earth share a common origin, a finding with significant implications for our understanding of how the Moon formed.

A path back to the Moon

Both Scott and Head say that it’s time to put the Moon back on the agenda for U.S. human spaceflight.

“One of the things we’ve been doing here with Dave and people from MIT, is working on a very straightforward approach to go back to the Moon,” Head said. “We have an architecture that worked beautifully: Apollo. Let’s figure out what 45 to 50 years of technology development has done to make that even better and cheaper.”

In a study performed last year, MIT engineers looked how upgrades to the Apollo lunar module — modern equipment, materials, propulsion, and computers — might increase the capacity to do science on the Moon without inventing an entirely new architecture. They found that such upgrades support a crew of three on the lunar surface instead of two, which was the limit during the original Apollo missions. Days on the lunar surface could be increased from three to seven. Stops on lunar traverses could be increased from 46 minutes — the maximum on Apollo — to more than three hours each.

“There’s so much more we could do now,” Head said. “If we’re serious about exploring the solar system and moving on to asteroids and Mars, then the Moon is absolutely the first place to go.”

And Scott reminded Brown students that the future of human space exploration rests in their hands.

“You all are in the absolute right position to participate,” he told them. “Not everybody’s going to be an astronaut, but you can be part of this team. If you can get a chance to be involved in something like that, I’d take it. It’s incredibly rewarding. You’ll learn a lot, and you’ll have a lot of fun.”