PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Thirty years ago people with addiction were often marginalized, stigmatized, and criminalized, and addiction studies were sometimes discouraged. Today the field is a point of pride at Brown University, which will celebrate the 30th anniversary of the Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies with a daylong colloquium Saturday, Sept. 21, 2013.

It’s a day to reflect on the field’s historic progress and to acknowledge that with millions still suffering, research, training, and treatment are as needed as ever.

Keynote speaker David Abrams came to Brown in the late 1970s as a clinical psychology intern interested in behavior therapy treatment of tobacco and alcohol addiction. He ignored the following advice: “Don’t do this as a research field. Tobacco use is simply a bad habit and you’ll never get promoted.”

But in Providence he found a stalwart cadre of empathetic academics and clinicians who didn’t see addiction as a question of immorality or bad habits. Among them were founding director Dr. David Lewis and the CAAS current director, Peter Monti. Lewis saw drug addiction this way: “Drug misuse is a complex social, economic, and physiological problem in which the actual substances play only one part.”

In the ’70s, Brown’s medical school and community health department had just begun, and interest in addiction was scattered around Brown and area hospitals. But in 1976 Dr. Stanley Aronson, Brown’s inaugural dean of medicine, recruited Lewis from Harvard to develop an addiction studies program at Brown. With substantial support from President Howard Swearer and key donors, Lewis launched CAAS in the 1982-83 school year. Monti joined the following year.

Under Lewis and Monti, who succeeded Lewis in 2000 as the Donald G. Millar Professor of Alcohol and Addiction Studies, CAAS has grown from a small office in Arnold lab with a budget of $1,500 into a prolific center with 28 full-time faculty members, $13.3 million in grant awards this year, and an enduring influence in research, medical and postdoctoral training, and local and national policy.

“From very small beginnings it became a national leader,” said Abrams. After he left Brown in 2004, he served as director of the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research at the National Institutes of Health and now serves as a professor at Johns Hopkins University. He also directs the Schroeder Institute for Tobacco Research and Policy Studies at the American Legacy Foundation in Washington, D.C.

Teaching and training

Lewis had been medical director of the Washingtonian Center for Addictions in Boston, then the nation’s oldest addiction treatment center. Aronson asked Lewis to convene a committee to develop a medical curriculum on addiction. Lewis, a Brown undergraduate alumnus, invited social science and humanities professors to join.

“The fact that I reached out to the college was an important part of our early development,” he said. Early participants included Bruce Donovan in classics, Dwight Heath in anthropology, and Demmie Mayfield, Barbara McCrady, and Richard Longabaugh in the medical school. “Eventually we talked about doing some projects together. The idea of a center came up.”

Lewis sought connections to the College to ensure the relevance of the center’s research to students, the community, and policy development. He taught an undergraduate course titled “Addiction in the American Consciousness” andwas chair of the Department of Community Health, which had a joint undergraduate concentration with sociology: “Health and Society.”

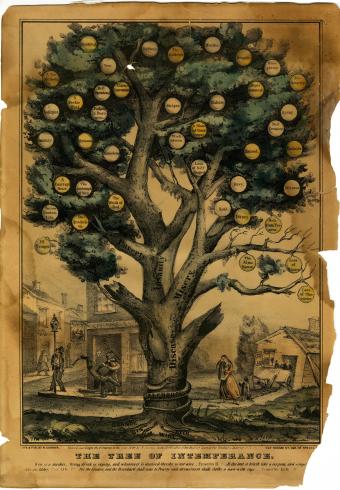

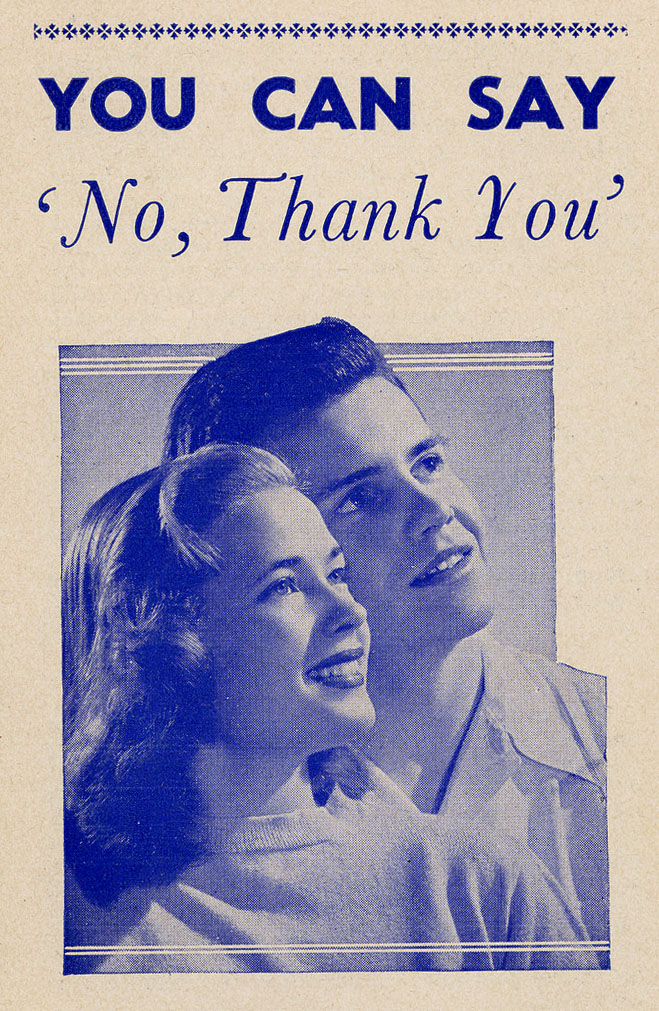

Lewis’s connections with the College also yielded a scholarly treasure: a rich and deep series of special collections at the John Hay Library on alcoholism and temperance. The collection preserves tens of thousands of items – documents, artifacts, advertisements — of both medical and sociological significance.

CAAS also built a program in postgraduate training that would go on to become its signature achievement. Lewis credited Longabaugh with organizing the original grants to launch the program in 1986. The program, which continues today, has trained about 150 postdoctoral researchers in its 27-year history. Many of those trainees have become influential faculty around the country and several have been invited to speak at the colloquium. Suzanne Colby, the program’s current training director, extended its reach internationally, Monti said. Last year, postdocs from Switzerland and the United Kingdom have been accepted for training and conducted research overseas as well.

Lewis also did not lose sight of his original mandate to develop a curriculum for medical students and residents that would infuse addiction studies into primary care and various specialties. The curriculum, conceived in Lewis’ living room and called Project ADEPT, became a national success. “It was used by 85 percent of the medical schools in the country in the 1980s,” Lewis said.

Decades of research

Faculty and trainees created influential ways of developing and evaluating various addiction treatments, which allowed them to inform federal and state policymakers about the value of treatment. Lewis’ strong clinical research foundation and passion for applying research to policy allowed him to serve many national and international committees and organizations. He became an adviser in the Clinton administration and worked with former U.S. Rep. Patrick Kennedy on legislation to ensure equal coverage by health insurers for addiction and mental illness.

Many researchers have made their mark in other areas of research. Abrams and Monti, both psychologists, studied how people respond to contextual cues that might make them relapse to smoking or drinking, for example, and worked to help patients develop coping skills.

Monti and center colleagues have written a book on a coping skills model of addictive behavior, currently undergoing its third revision. Monti has also worked to advance and expand the technique of the motivational interview (MI), a psychosocial intervention that helps patients understand their behavior and how it could change. He has also extended the MI to adolescents.

“When our four children were teenagers there was an epidemic of alcohol-related deaths in East Greenwich,” Monti said. “After the third funeral the kids went to, they said, ‘Dad, this is something you know a whole lot about. How can we help?’”

Work on teen addiction continues in the center. One of the center’s major current grants is “iSay,” a five-year project led by Kristina Jackson, to survey middle school students around Rhode Island in hope of determining what motivates some kids to experiment with drinking while others don’t.

CAAS has several other major projects. One is the Alcohol Research Center on HIV (ARCH), in which researchers led by scientific director Christopher Kahler are studying the physiological and psychological interplay of alcohol, sex risk, the virus, and antiretroviral medications; and SAFER, a study now in its 17th year of testing psychological interventions in community hospital emergency rooms to affect the combination of alcohol and risky sexual behavior. Monti leads those two projects and is co-PI with Damaris Rohsenow of the famed postdoctoral training program.

Another long-lived project, in its 18th year, is the Addiction Technology and Transfer Center of New England, headed by Daniel Squires. The ATTC provides distance learning and continuing education programs, sustains regional organizations to support the recovery community, and works with Rhode Island College to support its Bachelor of Science degree in Chemical Dependency and Addiction Studies. ATTC is a model for the dissemination component of the ARCH, Monti said.

In recent years the Center has accelerated its studies to identify genetic factors that might predispose people to addiction, or that might help predict who would be more or less responsive to different treatments. John McGeary and Valerie Knopik lead this area. “We have done some of the seminal work identifying which patients would be most responsive to a certain types of pharmacotherapy,” Monti said.

The symposium and the future

From Lewis’ perspective, the rapid advances in addiction genetics, neuroscience and psychology are bittersweet.

“The scientific understanding of what addiction is has changed phenomenally,” he said. “But the way that’s been able to be applied to prevention and treatment is very discouraging still. The science has moved much faster than its application.

“We do have good treatments, we do have good results, and the public understands the need for it better than they ever did,” he said. “We’re moving in the right direction but much too slowly.”

At the symposium, which begins at 8 a.m. with remarks by Monti and Brown President Christina Paxson, followed by Abrams’ keynote, current faculty and program alumni will lay out the cutting edge of research in the field as they work toward those needed advances. They’ll cover topics ranging from the etiology of addiction to current treatment research. Professionals who attend will receive continuing education credits.

Jennifer Read of the University of Buffalo will describe the individual and environmental factors that contribute to teen drinking. Brown’s Tara White will talk about what neuroimaging can tell us about effects of drugs and alcohol in the brain. Harvard’s John Kelly will present on the role and effectiveness of patient mutual-help groups, such as Alcoholics Anonymous.

Over the next 30 years it will be advances in science and empirically based treatments, rather than enforcement, that will likely advance the fight against addiction, Monti said.

“I would hope that the emphasis is placed more on treatment and away from the supply side of the equation,” he said. “We’ve had so many years of failure with respect to this War on Drugs.”

Over time, through research and teaching, the nation’s knowledge, s, and policy on addiction have changed — a development CAAS helped achieve and now celebrates.