PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Before new classes demanded the blood, sweat, and tears of the University’s newest students, adolescent sleep expert Mary Carskadon had politely asked for their blood, cheek cells, and sleep habits. In what is becoming something of a new school year tradition, hundreds of students from the University’s 1,541-member incoming class have signed up to help her study the effect of college life on sleep and health.

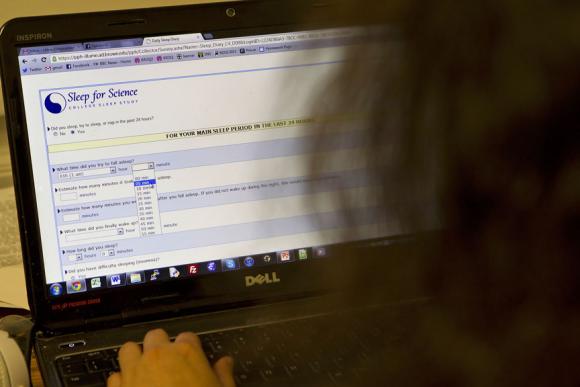

Scores of students trickled out of the rain and into the Metcalf building the Tuesday after Labor Day to join Carskadon’s study, now in its fourth year. As even more students did for two days priior, they filled out surveys, attended a consenting session and, if they were willing, filed down the hallway to swab cells from inside their cheeks, get height and weight measurements, and fill four small vials of blood. Over the next several months, the students will contribute daily sleep and diet diaries and fill out somewhat more probing biweekly surveys to assess their mood, sleep habits, and other lifestyle behaviors.

At one of the day’s many consenting sessions, Carskadon, professor of psychiatry and human behavior in the Alpert Medical School and at Bradley Hospital, briefed three female students about all this, and then grinned as she introduced the study’s signature moment.

“We’re coming to the most fun thing,” she said. “That’s the spit-in.”

The night of spit, scheduled for the first weekend in November in a room with purposely dimmed lights, will yield each student’s levels of the hormone melatonin, which indicates, as Carskadon says, “what time it is in your brain.” It will be a somewhat odd denouement to a semsester serious research.

All of the data is meant to help Carskadon and her colleagues learn more about the biological and psychiatric effects of sleep at an important moment in late adolescence. Sleep in college hasn’t been studied thoroughly even though the start of college is typically a moment of newfound independence and self-reliance for teens.

“It’s one of those pivotal life events,” Carskadon said.

Sleep and genes

Carskadon has begun to report interesting results from prior years. In June in the journal Sleep, for example, she reported that students with a specific genetic difference, known as a polymorphism, were more vulnerable to depressed mood if they didn’t get enough sleep than students without the polymorphism, even if they also were shorter sleepers.

This year Carskadon is enhancing her data in important ways. In prior years she asked students to self-report height and weight but this year she’s measuring it precisely, both in September and November. She’s also planning to have the blood samples examined for “epigenetic” measures, such as gene expression and methylation (a chemical alteration to DNA associated with changes in gene expression). This will allow her to assess whether varying levels of sleep affect how students’ bodies react at a genetic level.

In the consenting sessions, Carskadon emphasized that students should indeed be motivated by science, even though they can build up an online piggy bank of about $150 in compensation for keeping diaries, spitting, and meeting other obligations of the study.

“This is not life-changing money,” she told the students. “You are not doing this study for the money, I hope. You are doing this because you are Brown students now and you are interested in science and are interested in making a contribution.”

That motivation is exactly drew students Paul Wojtal of Oberlin, Ohio, and Chloe Kilman-Silver of Newton, Mass., through the rain to Metcalf.

Kilman-Silver said she’s no stranger to sleep studies. She offered that she suffers from a sleep disorder and characterized five hours of slumber as a good night.

“I think that sleep studies are important,” she said.

And Wojtal agrees that sleep itself is important.

“I certainly want to make sure I sleep enough and that I’ll be well prepared for classes,” he said.

That’s what learned researchers like Carskadon might call a healthy attitude.