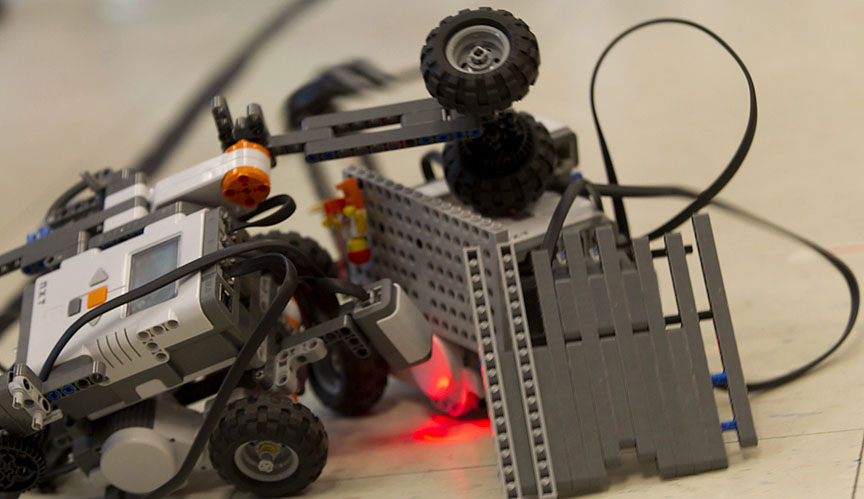

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Like sumo wrestlers, two LEGO® robots made their way around an oval ring, grabbing, swatting at each other, and trying with great gusto to push the other robot out of the ring to win the match. Ten young boys — third, fourth, and fifth graders — at the Paul Cuffee Middle School in Providence cheered on their creations, watching in delight as their aggressor responded to pre-programmed commands and light sensors to make their way around the ring in pursuit of the opponent. At each turn, parents and volunteer instructors joined in the cheering at the school’s cafeteria last Friday, July 20th. It was the culmination of a three-week pilot program designed to pique children’s interest in engineering and computer science.

The LEGO® robotic program was a partnership between Brown’s Science Center and the Paul Cuffee Middle School. Ten student participants were divided into two teams — the Panthers and the Demons of Nothingness — and instructed in the finer points of computer programming and engineering using LEGO® robots as the teaching tool. Students used a kit that not only contained LEGO® pieces but robots’ “brains,” which were connected to laptops so students could program the brains to respond to light, touch, ultrasonic, sound, color, temperature, accelerometer, compass, and radio-frequency identification sensors.

Brown students Mike Lazos, a computer engineering concentrator, and Raymon Baek, whose concentration is in mechanical engineering, helped the students design, build and program robots for four hours every day during the three-week summer program. According to instructor Baek the program was a tremendous success.

“The kids were very bright and went beyond our expectations,” Baek said. “We always finished the planned curriculum a lot quicker than expected, which kept Mike and me improvising to stay ahead of the students.”

The students used visual programming software with easily readable icons and distinct colors for each type of tile. For example, movement tiles would tell the robot to move and sensor tiles would tell the program to rely on a specific sensor. The program used wait statements (e.g., wait for a certain sound level or touch sensor to be activated), switch statements (e.g., if the light sensor detects a dark area, move right; move left for a bright area), and loops. These commands made it possible for the robots to compete in the sumo wrestling challenge and an obstacle course.

The students had to be creative about using sensors to follow a zigzag path through the obstacle course, navigating through various boxes, capturing colored balls from a central area, and bringing them back to their starting points. The Panthers easily won the obstacle course because they built a robot that had a robotic arm that pulled nearly all the balls back to its starting point in one trial.

As for the battle arena, the Demons of Nothingness won because their robot was very bulky and stable. “Mike and I decided to surprise them by introducing our own robot that we assumed was invincible,” said Baek. “We had the three robots fight it out in the ring. To our surprise, our robot was pushed out of the ring and the Demons of Nothingness reigned victorious.”

During the three-week program, the instructors gained some insight about the challenges of teaching. “The boys loved to build, but the programming, which required them to sit still and concentrate was a challenge. They need to get up and run around every so often to burn off some energy,” said Baek.

In this pilot effort, all participants including the students, teachers, learning concept, and execution proved to be a perfect match.