Art and science sometimes seem only to share relative extremes — science is literal, fundamental and dispassionate; art is symbolic, abstract, and emotional — but they often find ways to meet. When dance, poetry, and a lecture on neurotechnology shared the stage at the Everett Dance Theatre in Providence recently, their intersection was a shared hope to restore expression to a young woman who cannot move or speak.

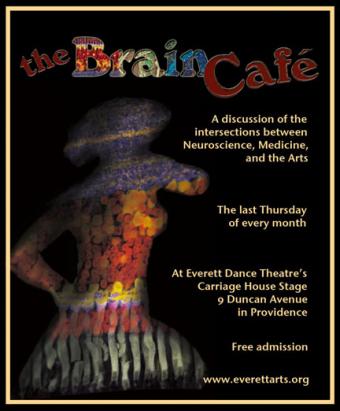

The gathering amid snow showers on the last night of March was one in a monthly series of events that Everett has dubbed Brain Café. The meetings are an opportunity for the company to try out sketches and gather information and inspiration for an upcoming multimedia dance and theater production called Brain Storm.

For this café, Everett invited Beata Jarosiewicz, a Brown University investigator in the neuroscience department, who works on the BrainGate team. Their goal is to read neural signals directly from within the brains of people with paralysis and to translate that code into instructions to control computers, wheelchairs, robots and prosthetics.

For all the recitals and research, the focus of this evening was the young woman seated front row center. Margaret Worthen, the victim of a stroke the week before her college graduation in 2006, now lives with what’s called “locked-in syndrome.” The night belonged to her story and the ways that art might communicate what she cannot — and the way science and engineering might someday restore her connection with the world.

Credit: David Orenstein/Brown University

In the evening’s most poignant vignette, dancers acted out the story of her life before and after the stroke as her mother Nancy’s prerecorded narration played over the theater’s speakers. Nancy, who sat right beside Margaret during the performance, was visibly moved.

“It was emotional,” Nancy said. Reading her essay for a recording was easy enough, she said, but seeing her daughter embodied anew through dance and knowing that Margaret was listening made the words much more poignant.

Then it was Jarosiewicz’s turn.

“This is going to be relatively dry compared to what you’ve just seen,” she warned, but from the litany of questions at the end it’s clear that she held the audience with her explanations and videos showing how a tiny electrode array implanted on the surface of the brain can give people who can’t move at least a limited ability to manipulate electronic devices around them with their thoughts.

Jarosiewicz, the daugher of an artist and an engineer, said she knows many artists have been excited by the futuristic prospects of people becoming more directly merged with machines, but she was still a bit puzzled about how a dance performance might approach paralysis.

“I think they did a really amazing job with it, I thought it was very beautiful,” she said. “Science benefits a lot from the display it gets via art to the general public. I really like that interaction. I seek it out in life.”

For the Everett Dance Theater’s part, it seeks to inform its art from a variety of sources, including science, said artistic director Aaron Jungels. Brown lecturer John Stein, for example, presented a neuroanatomy crash course at a previous Brain Café, complete with a real brain on a table.

“The audience gets so excited to have scientists there and to talk to and ask questions of,” Jungels said.

Much of the show — and how Everett’s rapidly accumulating neuroscience knowledge will be integrated into it — is still far from settled, Jungels said. But that’s another similarity that science and art share. The stock and trade of scientists is delving into the unknown, he noted.

“And that’s exactly the way we feel about art and our approach to creating work,” he said. “We go into this broad area but we don’t know exactly what the piece is going to be. The process tells us what it’s going to be by what we uncover.”

Brain Storm will debut Nov. 12 in Providence at Veterans Memorial Auditorium in Providence, and will then take the stage in at least four other venues in New England before perhaps touring beyond the region in 2012.