PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Animals from tiny worms to human beings have a love-hate relationship with fats and lipids. Cholesterol is a famous example of how they are both essential for health and often have a role in death. A new study reveals another way that may be true. Researchers working in nematodes and mice found that a naturally occurring protein responsible for transporting fats like cholesterol around the body also hinders essential functions in cells that increase life span.

When the scientists genetically blocked production of the worms’ yolk lipoprotein, called vitellogenin (VIT), the nematodes lived up to 40 percent longer, the study showed. Mice, humans and other mammals produce a directly analogous protein called apolipoprotein B (apoB), and therapies have been developed to reduce apoB to prevent cardiovascular disease.

The new research suggests that there might be a whole other benefit to reducing apoB. Data from the nematodes indicate that apoB’s evolutionary cousin VIT prevents long life span by impairing the ability of cells to use and remodel fats for healthier purposes.

“That protein, which has an ortholog in humans, is a major decider of what happens to fat inside intestinal cells,” said Louis Lapierre, assistant professor of molecular biology, cell biology and biochemistry at Brown University and senior author of the study in the journal Autophagy. “If you reduce the production of these lipoproteins you allow the fat to be reused in different ways.”

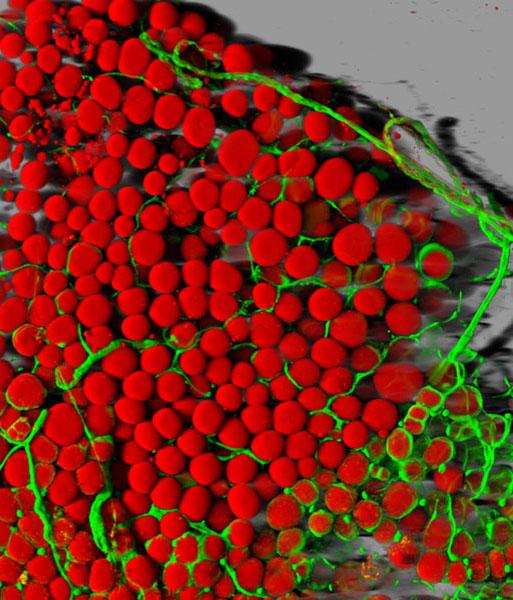

Lipophagy is the process of breaking down large quantities of built-up fats and reusing them for other purposes. The new study showed that the longevity benefits associated with increased lipophagy are hindered by too much VIT.

“Since we see in the worm that we can extend life span by silencing this protein, we reason that it could be a promising strategy to prevent age-related disease in humans." Photo: Nicole Seah

Lapierre’s team, including lab manager and co-lead author Nicole Seah, demonstrated the link directly. Some experiments, for example, showed that the life span benefits of blocking VIT didn’t occur if autophagy was blocked in other ways. They also showed that VIT hinders a related process called lysosomal lipolysis, the endpoint of lipophagy which catalyzes fat breakdown.

In mice the team connected this effect to another well-known model of increased longevity: dietary restriction. Many studies have shown that animals that eat less live longer. In this study the researchers showed that calorie-restricted mice produced less apoB.

In nematodes, the normal purpose of VIT is thought primarily to involve the transport of fats from the intestine to the reproductive system to nourish eggs and to aid in reproduction. Similarly in mammals, Lapierre said, a purpose of apoB is to transfer fats away from the intestine and liver toward other tissues where they can either be used or stored.

“Altogether our data supports a model in which lipoprotein biogenesis prevents life span extension by distributing lipids away from the intestine and by negatively regulating the induction of autophagy-related and lysosomal lipase genes, thereby challenging the animal’s ability to maintain lipid homeostasis and somatic maintenance,” the authors wrote in the study.

Help for humans?

Of course nematodes and mice are not people, but Lapierre said he is optimistic that these findings could eventually matter to human health. He’s not alone. Other labs are currently investigating the relationships between lipoproteins, autophagy, and life span.

“Since we see in the worm that we can extend life span by silencing this protein, we reason that that it could be a promising strategy to prevent age-related disease in humans,” Lapierre said.

Earlier this year Lapierre earned a grant from the American Federation for Aging Research to continue his work. His lab group is now looking at the global effects of limiting VIT and apoB in animals.

In humans, he said, a major unanswered question is what effect silencing apoB would have on fat remodeling in the liver and the intestine.

The new research finds that at least in nematodes, keeping fats in the intestine allows cells to carry out processes that are linked to longer life span.

The paper’s other co-lead author is C. Daniel de Magalhaes Filho of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Salk Institute. The study’s other authors are Anna Petrashen, Hope Henderson, Jade Laguer, Julissa Gonzalez, Andrew Dillin, and Malene Hansen.

In addition to AFAR, the National Institutes of Health provided funding for the study (grants K99AG042494 and R00AG042494).