PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — From engineering to emergency medicine, Brown University researchers, physicians, and athletics staff have made concussion and other brain injuries a priority in the lab, in the clinic, and on the field.

Brown Medicine magazine explored many projects in the fall 2013 cover story, “Ahead of the Game.”

“Concussion is the most prevalent sports injury,” said Dr. Neha Raukar, assistant professor of emergency medicine, in the story. “Every soccer mom knows about it.”

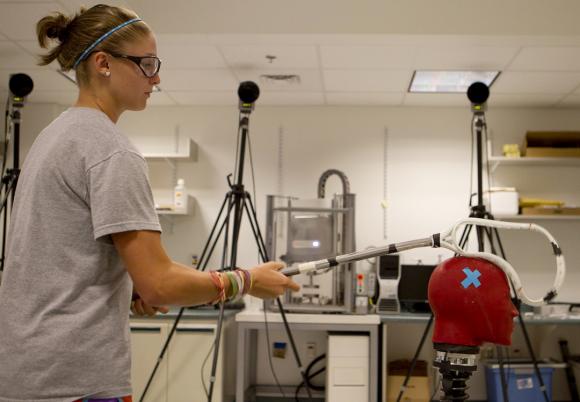

Among the research projects in the story is ongoing work by Joseph Trey Crisco, professor of orthopaedics, who has embedded sensors in athletic headgear to measure the accelerations of head blows in football, hockey, and girls’ lacrosse.

Christian Franck, assistant professor of engineering, studies brain injury at the level of individual cells. He made news recently with his studies of how shocks, such as from explosions, can do unseen neurological damage.

Other researchers focus on diagnostics. Earlier this year, Adam Chodobski, associate professor (research) of emergency medicine, and colleagues proposed a new panel of biomarkers for detecting concussion. Four proteins in the blood allowed the researchers to distinguish concussions from other injuries.

A reliable biomarker would change the game for concussion diagnosis, but the first assessment often occurs on the field. Brown head athletic trainer Russell Fiore described how Brown addresses sports concussions from initial diagnosis through treatment.

Meanwhile in this month’s issue of the Rhode Island Medical Journal Dr. Jon A Mukand, clinical assistant professor of orthopaedics, and co-author Marilyn Serra provide an overview of concussions in youth sports. Kids and teens are at especially great risk.

“Although most (80 to 90 percent) of concussions resolve within seven to 10 days, the recovery process can be longer and more complicated in children and adolescents,” they wrote. “Furthermore, younger athletes have a higher risk of severe symptoms and cognitive decline. This age difference in recovery and prognosis is probably related to the ongoing development of a child’s brain.”