PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — New calculations suggest that vast valley networks that spider across the southern highlands of Mars may have been carved by a surprisingly small volume of water.

The study, published in the November issue of Planetary and Space Science, finds that the minimum water volume required to carve the valleys could have flowed through in as little as a few hundred to 10,000 years. The findings are consistent with the idea that early Mars may have been cold and icy, with water flowing sporadically on the surface in response to short-term climate changes, say the Brown University researchers who led the study.

“The valley networks represent much of the evidence for why many scientists think ancient Mars was warm and wet, which implies that there was a lot of water flowing for a long period of time — perhaps millions of years,” said Jim Head, the Louis and Elizabeth Scherck Distinguished Professor of the Geological Sciences and co-author of the new paper. “But this analysis suggests that the valleys could have been carved by a smaller volume of water over a potentially shorter period of time. That gives us guidance about trying to understand what was really going on with the early Mars climate.”

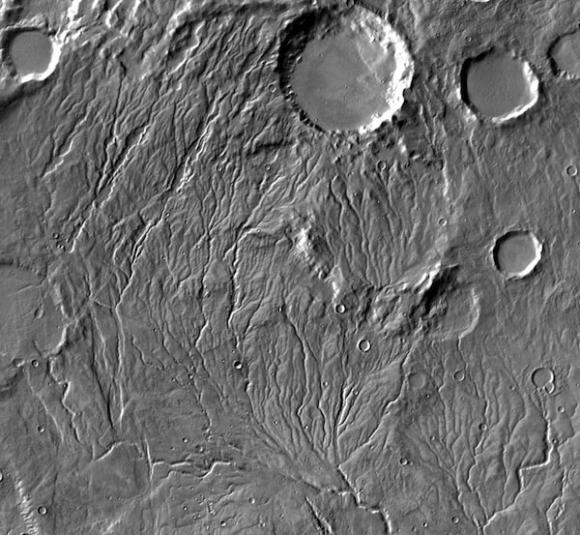

The Martian valley networks were first discovered during the Mariner 9 mission in the 1970s. The branching channels, typically up to four kilometers wide, often stretch for thousands of kilometers across the southern highlands, some of the most ancient surfaces on the Red Planet.

The waters that carved the valleys are thought to have stopped running as much as 4 billion years ago. That makes figuring out just how much water flowed through the valleys “a very difficult calculation to do,” said Eliott Rosenberg, an undergraduate student at Brown who led the research.

For starters, Rosenberg needed to figure out exactly how much sediment had been excavated from the valleys. He used data from the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA) to get an average cross-sectional area for the valleys. He multiplied that by previous measurements of the length of the valleys to get a sediment volume.

The harder part, however, was figuring out how much water it would take to move that volume of sediment. One way of doing that requires estimating the ratio of sediment and water that traveled through the valleys per unit of time. Since the rivers are long gone, previous researchers could only make guesses at the ratio. Rosenberg wanted to find something a bit more concrete.

In the course of his research, he came across a report by the Texas Department of Transportation assessing how well different types of drainage tunnels are able to handle sediment fluxes. Within that report was raw data on fluid and sediment transport for a large number of rivers and streams. Using those data, Rosenberg found that he could get a decent estimate of the fluid/sediment ratio if he could figure out the strength of the flow.

“The strength of the flow through the valleys turns out to be something we can estimate,” Rosenberg said. “It’s a function of the slope of the valleys — which we could get from the MOLA data — as well as the depth of the flow and the size of the grains on the riverbed, because that affects how fast the water can flow and how much sediment it can pick up,” Rosenberg said.

Using the morphology of the valleys and established hydrological equations, Rosenberg estimated the depth of the ancient Martian rivers to be between 1 meter and 16 meters deep and a minimum grain size to be between 1 mm and 6.2 mm. The grain size yielded by those theoretical calculations turns out to be a close match for the grain sizes the Curiosity rover found in Gale Crater, a nice confirmation of the theoretical approach.

Using those numbers, Rosenberg was able to estimate a flow strength for the Martian rivers. He could then use the raw data from rivers on Earth to estimate a total water volume.

The calculations yielded a volume of between three and 100 GEL (global equivalent layer). GEL is a commonly used term when scientists discuss water on Mars. It means that if one were to take all the water that flowed through the valleys over time and spread it evenly across the Martian surface, it would be between three and 100 meters deep. That might sound like a lot of water, but it’s actually quite a small amount, the researchers say. Mars is considered to be a very dry place at present, yet its current water inventory, most of which is trapped in frozen ice caps, is around 34 meters GEL.

“This means that the amount of water that we calculate may have flowed through the valleys is on the same order as the amount of water on the planet today,” Head said. “The implication here is that the valleys may well have been carved by a much smaller volume of water than many people previously thought.”

Rosenberg and Head estimate that the volume of water yielded by these calculations could have flowed through the valleys in a few hundred years to 10,000 years. That’s a much shorter period than the millions of years of flowing water often envisioned for early Mars.

The researchers point out that the assumptions they used were aimed at finding the minimum amount of water required to carve the valleys. It could indeed have been more, but it didn’t necessarily need to be. “What we’re saying is that you could still form these valleys even if ancient Mars wasn’t all beach balls and cabanas,” Head said. “The warm and wet model of ancient Mars is very hard to square with estimates of the ancient Martian climate. This work makes the case that these valley networks could still form if Mars was cold and icy with shorter periods flowing water.”