PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — For nearly 50 years Medicare has required patients to endure at least a three-day stint in the hospital before they become eligible for coverage of skilled nursing care afterward. A new study, however, finds that the main consequence of waiving the rule, as Medicare Advantage plans commonly do, has been a good one: less time in a bed and a gown for those who go on to skilled nursing care.

“This may be a way for Accountable Care Organizations to reduce health care costs while not adversely impacting outcomes.”

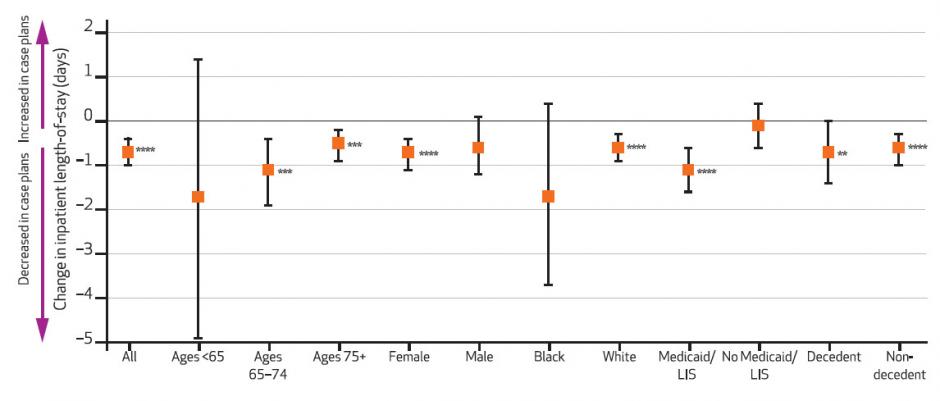

Specifically, the Brown University research team found that between 2006 and 2010 the average time in the hospital per year increased by half a day among 140,739 people in 14 plans that never waived the rule, but decreased by 0.2 days among 116,676 people in 14 otherwise similar plans after they waived it. That net difference of 0.7 fewer days on average in the hospital — a 10 percent relative reduction — likely saved Medicare Advantage plans money, but also meant less time before patients could move to the next phase in their recovery and less time when they were at risk of experiencing hospital-acquired complications, such as an infection or blood clot.

“This policy dates back to the mid-1960’s, when the average length of a hospital stay was two weeks,” said Dr. Amal Trivedi, associate professor of health services, policy and practice at Brown University and corresponding author of the study in the August issue of Health Affairs. “Requiring patients to stay in the hospital for three days before they can be transferred to a skilled nursing facility may unnecessarily lengthen hospital stays, leading to more spending, but also subject patients to unnecessary complications arising from hospital care.”

Meanwhile, the researchers found no evidence of several potential negative consequences of waiving the rule: Did members of plans that waived the rule have more skilled nursing admissions? No. Were they in skilled care for longer? No.

The researchers also checked to see if patients in rule-waiving plans had more hospital admissions. They did not.

“It wasn’t as if discharging them early and letting the patients go to the nursing home just led to the patient going back into the hospital,” said lead author Regina Grebla, a Brown alumna and research consultant.

It was not possible in the study to measure directly how many stays under rule-waiving plans were less than three days because the study data did not track every individual episode of care. Instead it counted the total hospital and skilled nursing admissions and days for each patient for each year.

An evidence-free zone

Studies of the issue have been few and far between. This one is the first to examine the data from the leeway Medicare Advantage plans have had to waive the rule. The last studies to look at the issue drew on data from 1988, when Congress briefly nixed the three-day rule under the quickly repealed Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act. At that time other policy changes under the act muddied the ability to evaluate the three-day rule on its own.

“Hospital and skilled nursing care have changed a lot,” Trivedi said. “This has been an evidence-free zone for the last 25 years.”

The new results suggest that the rule could be re-evaluated for both traditional fee-for-service Medicare and for emerging Medicare Accountable Care Organizations, in which a group of health care providers share in the quality and costs (and potential savings) of care for a patient.

“To what extent would these results generalize to traditional Medicare and to Accountable Care Organizations? It’s difficult to say,” Trivedi said. “But it suggests that waiving the three-day stay policy, at least in a managed care environment, did not result in increased use of skilled nursing facilities or increased length of stay in skilled nursing facilities, and appeared to have led to a pretty substantial drop in length of stay in the hospital.

“This may be a way for Accountable Care Organizations to reduce health care costs while not adversely impacting outcomes,” Trivedi said.

In addition to Trivedi and Grebla, the paper’s other authors are Laura Keohane, Yoojin Lee, Lewis A. Lipsitz, and Momotazur Rahman.

The Alliance for Quality Nursing Home Care and the National Institute on Aging (grants: R01 AG044374 and P01 AG027296) funded the research.