PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Between December 2009 and February 2011, health workers with the AMPATH Consortium sought to test and counsel every adult resident in the Bunyala subcounty of Kenya for HIV. A study in the journal Lancet HIV reports that the campaign yielded more than 1,300 new positive diagnoses, but few of those new patients sought health care.

“Home-based counseling and testing (HBCT) provided a diagnosis to nearly 40 percent of people living with HIV in this subcounty who otherwise most likely would not have gone for HIV testing,” said study lead author Becky Genberg, assistant professor (research) of health services, policy and practice in the Brown University School of Public Health. “They therefore would not have known about their HIV infection and not had the opportunity to change their behavior to protect others.”

AMPATH’s HBCT program is part of a strategy to identify all individuals living with HIV in the catchment area, start them on antiretroviral medication as soon as possible, and help them stay on their medications. Antiretroviral medication not only suppresses HIV infections for most patients but also reduces their ability to transmit the virus.

“We are working on a variety of studies, all designed to understand the barriers facing the newly diagnosed, and to implement and evaluate strategies to increase their engagement and retention in HIV care over time.”

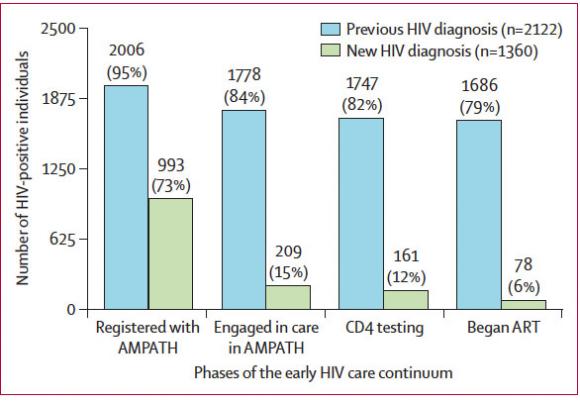

In Bunyala, home to about 66,000 people, the HBCT program tested about 32,000 adults. Among them, 3,482 had HIV. Of those, 2,122 already knew they were infected, but 1,360 did not know it yet.

A major finding of the study is that three years later only 15 percent of the newly diagnosed people had engaged in care for their infection. A likely reason why, Genberg said, is that newly diagnosed people typically don’t yet feel sick.

“That so few linked to care following HBCT is a call for innovative and creative strategies to work alongside HBCT to support the mostly healthy, asymptomatic newly diagnosed to engage with care in a way that is meaningful for them,” Genberg said.

In an editorial in the journal, Rashida Ferrand of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine said the study sounds a warning that home-based testing must be paired with effective ways to convince newly diagnosed patients to seek help.

“Unless paired with interventions targeted at hard-to-reach populations, the diagnosing of undiagnosed individuals in many settings will not be cost-effective and will have little effect on individual and population viral suppression,” she and colleagues wrote.

Genberg, who has been in Kenya this winter, said she is working with Kenyan collaborators on developing the needed interventions: “Right now we are working on a variety of studies, all designed to understand the barriers facing the newly diagnosed, and to implement and evaluate strategies to increase their engagement and retention in HIV care over time.”

In addition to Genberg the study’s authors are Joseph Hogan and Corey Duefield of Brown; Violet Naanyu, Juddy Wachira, and Samson Ndege of Moi University in Kenya; Edwin Sang, Monicah Nyambura, and Michael Odawa of AMPATH; and corresponding author Paula Braitstein of the University of Toronto.

The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief funded the study though USAID (grant AID-623-A-12-0001). Additional support came from the National Institutes of Health (K01MH099966) and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.