PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — A study of more than 12 million acute care hospitalizations over a five-year span found that as quality improved on each of 17 measures so did racial and ethnic equity. Nine major disparities evident in 2005 had mostly or totally disappeared by the end of 2010.

The study, led by Dr. Amal Trivedi of Brown University and published in the New England Journal of Medicine, found that care for blacks and Hispanics became better and more equitable when comparing hospitals principally serving whites to hospitals principally serving minorities, and when comparing changes in care over time within the same hospitals.

“This is happening because hospitals that disproportionately serve minority patients improved faster, and it’s also the case that [individual] hospitals are delivering more equal care to white and minority patients over time,” said Trivedi, associate professor of health services, policy, and practice in Brown’s School of Public Health and a hospitalist at the Providence Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

Widespread evidence remains for racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in medicine, Trivedi said, and these results, while very positive, address only a narrow spectrum of care delivery. But they suggest that when hospitals strive to improve quality, they can also improve equity.

“The foundation of quality improvement rests on reducing and eliminating unwanted variation,” Trivedi said. “Efforts to standardize care and make it more consistent may close gaps.”

“The foundation of quality improvement rests on reducing and eliminating unwanted variation,” Trivedi said. “Efforts to standardize care and make it more consistent may close gaps.”

Co-author Dr. Michael Fine, professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh and director of the Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion at the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System, said that the results, while encouraging, concern services provided, not outcomes achieved.

“It is heartening that we found higher quality of care overall and large reductions in racial and ethnic disparities in health care for patients with these common conditions,” he said. “However, it is critically important to demonstrate that these improvements in care are accompanied by better patient outcomes. Future studies are needed to investigate if racial and ethnic disparities in mortality have also decreased over time.”

Improving quality, equity

The data in the study arose from an effort launched in 2004 by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to measure hospital care. The Inpatient Quality Reporting Program led to disclosures by 98 percent of nonfederal acute care hospitals in the United States about how often they performed recommended treatments among patients with heart attack, heart failure, or pneumonia.

Hospitals publicly report aggregate data without regard to race or ethnicity. Trivedi and Fine’s research team looked at the records to study performance trends in 12,447,154 hospitalizations from the beginning of 2005 to the end of 2010 among non-Hispanic whites, blacks, and Hispanics. They looked at the rates by race and ethnicity for 17 procedures across the three medical conditions. They looked at changes in each hospital’s performance over time as well as comparisons among hospitals that predominantly served whites and hospitals that predominantly served minorities.

Hospitals publicly report aggregate data without regard to race or ethnicity. Trivedi and Fine’s research team looked at the records to study performance trends in 12,447,154 hospitalizations from the beginning of 2005 to the end of 2010 among non-Hispanic whites, blacks, and Hispanics. They looked at the rates by race and ethnicity for 17 procedures across the three medical conditions. They looked at changes in each hospital’s performance over time as well as comparisons among hospitals that predominantly served whites and hospitals that predominantly served minorities.

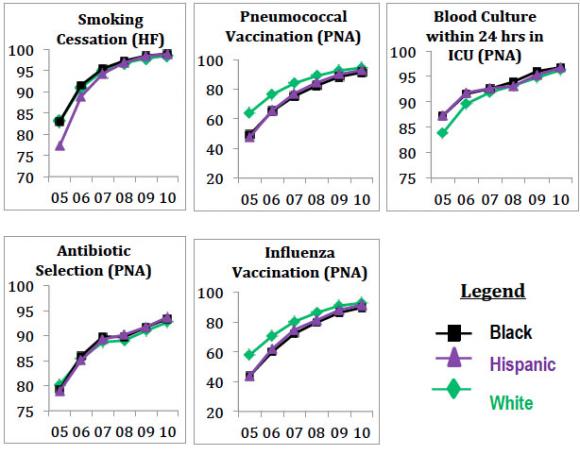

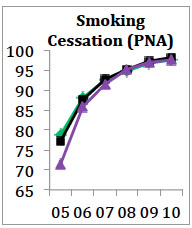

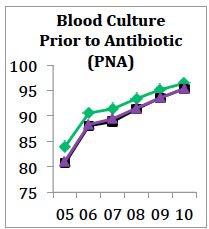

For all racial and ethnic groups, hospitals improved on all 17 metrics during the period, meaning that they provided all the recommended treatments more often. The overall range of improvements was between 3.4 and 58.3 percentage points as widely performed procedures such as giving an aspirin to heart attack patients inched up, and as less commonly performed treatments, such as giving a flu vaccine to pneumonia patients, became more standard.

At the beginning of 2005, there were nine metrics — three among blacks and six among Hispanics — for which there were white vs. minority gaps greater than five percentage points. By 2010, all the gaps had narrowed significantly. Gaps between blacks and whites tightened by 8.5 to 11.8 percentage points. Disparities between whites and Hispanics narrowed by 6.2 to 15.1 percentage points.

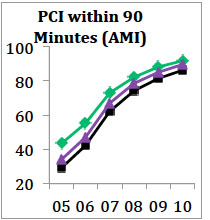

The case of PCI within 90 minutes

Take, for example, the case of providing percutaneous coronary intervention to heart attack patients within 90 minutes of arrival at the hospital. The complex but life-saving procedure involves clearing a blood clot in an artery in the heart, thereby restoring blood flow and improving the odds of surviving a heart attack. In 2005, PCI was performed within 90 minutes for whites 43.4 percent of the time, for blacks 29.2 percent of the time and for Hispanics 34.1 percent of the time. By 2010, it was done for whites in 91.7 percent of cases, for blacks in 86.3 percent of cases, and for Hispanics in 89.7 percent of cases.

When the researchers accounted for possibly confounding variables such as patient age, sex, other medical conditions, and socioeconomic status, and for hospital characteristics such as size, teaching status, and how often hospitals treat the three conditions, the remaining gaps in 2010 attributable to race or ethnicity proved even narrower: 3.8 percentage points for blacks and 1.1 percent for Hispanics, as compared to whites.

When the researchers accounted for possibly confounding variables such as patient age, sex, other medical conditions, and socioeconomic status, and for hospital characteristics such as size, teaching status, and how often hospitals treat the three conditions, the remaining gaps in 2010 attributable to race or ethnicity proved even narrower: 3.8 percentage points for blacks and 1.1 percent for Hispanics, as compared to whites.

The statistical story of PCI is one in which a concerted national effort to make a crucial procedure a standard of care led to a significant narrowing — but not complete elimination — of what were glaring disparities only five years before.

Trivedi said he is encouraged by the results showing widespread improvement in overall quality and racial equity. As he and his co-authors wrote in the journal, equity and quality are inseparable criteria of good medical care.

“Equity is a key dimension of health care quality,” they wrote. “Therefore, gauging progress in quality of care must explicitly consider whether gains have also occurred in health care equity.”

In addition to Trivedi and Fine, the paper’s other authors are Dr. Wato Nsa, Leslie Hausmann, Dr. Jonathan Lee, Allen Ma, Dr. Dale Bratzler, Maria Mor, Kristie Bause, and Fiona Larbi.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services provided funding for the study (contract HHSM-500-2011-OK10C).