PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — To address the HIV epidemic in Mexico is to address it among men who have sex with men (MSM), because they account for a large percentage of the country’s new infections, says Omar Galárraga, assistant professor of health services policy and practice in the Brown University School of Public Health.

A major source of the new infections is Mexico City’s male-to-male sex trade, Galárraga has found. In his research, including detailed interviews and testing with hundreds of male sex workers on the city’s streets and in its clinics, his team estimates that the prevalence of the virus among them could be as high as 40 percent. Because of inconsistent condom use and high degrees of infection among many sex workers, about 8 percent of their customers and other partners become infected each year. Infection can spread further from there.

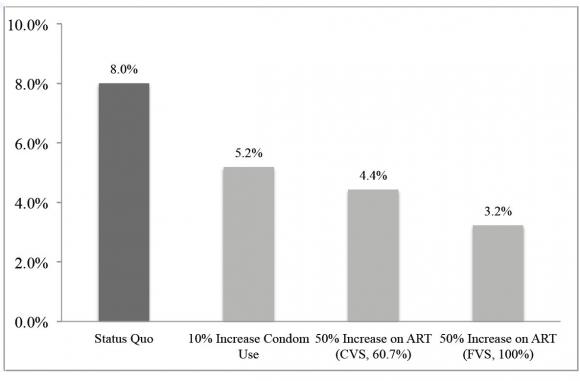

But out of such seemingly bleak knowledge, Galárraga said, there is also hope. In a new study in AIDS and Behavior, Galárraga, lead author João Filipe G. Monteiro, and colleagues project that a 10-percent increase in condom use by HIV-positive male sex workers would reduce an 8 percent annual infection rate among their partners to 5.2 percent. Meanwhile, increasing the number of HIV-positive sex workers on antiretroviral medications by 50 percent would slash the infection rate among clients to 4.4 percent. More aggressive interventions could cut the rates further.

“There is universal access to HIV treatment in Mexico, so if this is implemented, especially among these key populations, it can really make a dent in the concentrated epidemic that Mexico has,” Galárraga said.

Mexico’s male sex trade

Making a big dent — and eventually bringing HIV infection rates down to zero — is the goal of Galárraga’s ongoing work in Mexico City, performed in conjunction with local authorities and colleagues there. For years he has been studying the epidemic in the city’s MSM community to determine how behavior and biology contribute to the virus’ spread and to determine how to intervene.

For the projections in the AIDS and Behavior study, he and his colleagues included data from screenings and interviews with 79 HIV-positive male sex workers 18 to 25 years old. (By now his team has gathered data from a total of 500 workers and counting).

Galárraga, Monteiro, and the team learned that in the week before their research interviews and testing, the 79 infected sex workers reported having 405 unique partners. They used condoms during sex in about three of every four of those encounters. Of the group, only 40 percent were receiving medication and a majority (about 53 percent) had a viral load above 10,000 copies of the virus per milliliter of blood, a threshold far above what’s presumed to make someone contagious.

In essence, then, the male sex trade in Mexico City presents a serious infection risk because many sex acts occur without condom use and with sex workers in whom HIV has not been adequately suppressed with medication.

Running the numbers

Using data gathered from the 79 workers and other published data, including estimates of infectiousness given different viral loads, Monteiro, a postdoctoral researcher, built a statistical model to forecast how effective different interventions — increased condom use or increased antiretroviral therapy — might be.

He ran the model 1,000 times each for various assumptions. He found that under the status quo of the epidemic, he was able to estimate the figure that on average 8 percent of partners of male sex workers were becoming infected each year (even accounting for the fact that about 20 percent of the partners were likely already infected to begin with). Increasing condom use by just 10 percent (i.e., from about 75 percent of the time to 82.5 percent of the time) reduced that rate to 5.2 percent. To reduce the infection rate by half (to 4.1 percent) would require increasing condom use by 20 percent (i.e., to 90 percent of the time), the models showed.

For increasing HIV treatment, Monteiro ran the models with two different assumptions: either that the viral suppression rate would be only 60 percent (a real-world level in the sex worker population) or the ideal of 100 percent.

With 60 percent viral suppression, getting 51 percent of sex workers into treatment (a 25-percent increase from the current number), the partner infection rate dropped to 5 percent. With 61 percent on such treatment, the rate dropped to 4.4 percent. If every sex worker were on treatment with 60 percent viral suppression, the infection rate among their partners would decline to 2.5 percent, Monteiro found.

Making interventions work

Galárraga and his collaborators have shared their research findings along the way with Mexico City officials who have taken action to help. To keep HIV-positive people linked to care, for example, the city passed a law providing free bus service for HIV-positive people so that they can more easily get back and forth to clinics.

Galárraga is also working with colleagues to counteract the economic incentive that sex workers have to forgo condoms. Customers offer sex workers more money for condomless sex. Galárraga’s research has determined what amount of conditional cash payments could be enough to convince sex workers to turn down that premium.

He has been able to use that data to help Mexican public health officials pilot a payments intervention program in hopes of making condom use more common.

“We know that the market inducements are against prevention,” Galárraga said. “So we think it’s in the best interests of public health to incentivize key populations to increase ART and to try to use condoms consistently.”

In addition to Galárraga and Monteiro, other authors include Brandon Marshall, Daniel Escudero, Dr. Timothy Flanigan, Don Operario, and Mark Lurie of Brown; Sandra G. Sosa-Rubí of the National Institute of Public Health (INSP) in Mexico; Andrea González of Clínica Especializada Condesa in Mexico City; and Dr. Kenneth Mayer of the Fenway Institute.

The U.S. National Institutes of Health (grants R21HD065525, T-32DA013911, P30AI042853), The Mexican National Center for HIV/AIDS Control and Prevention (CENSIDA), and Brown University supported the research.