PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Imagine that a time machine has transported you to the Australian outback 100,000 years ago. As you emerge, you see a huge kangaroo with a round rabbit-like face foraging in a tall bush nearby. The animal’s surprising size makes you gasp aloud but when it hears you, becoming equally unnerved, it doesn’t hop or lumber away on all fours and tail like every kangaroo you’ve seen in the present. It walks on its feet. One at a time. Like you.

In a new paper in the journal PLoS ONE, a team of researchers led by Christine Janis, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at Brown University, posits that the Pleistocene members of the now extinct family of sthenurine kangaroos were likely bipedal walkers. The scientists make their case based on a rigorous statistical and biomechanical analysis of the bones of sthenurines and other kangaroos past and present. In all, they made nearly 100 measurements on each of more than 140 individual kangaroo and wallaby skeletons from many genera and species.

The investigation started in 2005 with a moment of intuition. Janis, an expert on the anatomy of other bygone Australian beasts such as the thylacine, was visiting a museum with a colleague. She beheld a sthenurine skeleton that displayed, among other traits, a sturdy rather than flexible-looking, spine. She began to wonder if it moved the same way modern, familiar kangaroos do.

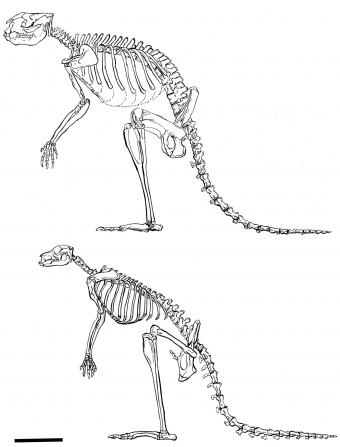

Ankle design, larger hips and knees suggest that sthenurines could put their weight on one leg at a time, an essential capability for walking on two feet. Image: Brian Regal

Janis and co-authors Karalyn Kuchenbecker, a former Brown undergraduate, and Borja Figuerido, of the University of Malaga, Spain, then spent years working to determine how sthenurines, known as “short-faced, giant kangaroos,” likely got around.

In the ensuing measurements and statistical analyses described in the paper, the researchers found many reasons to hypothesize that for locomotion, stheneurines were fundamentally unlike the large modern red and grey kangaroos – the modern-day favorites of zoo-goers. On statistical plots charting trait after trait of hind limb bones, sthenurines consistently stood apart from their hopping cousins. Other researchers had already noted other differences — sthenurines had teeth for browsing for food, for example, rather than grazing, like the large kangaroos of today.

From a biomechanical standpoint, the anatomy of all sizes of sthenurines would have made them poor hoppers, the researchers found. For the especially giant species, one of which may have weighed as much as 550 pounds, hopping might have been very hard to do.

“I don’t think they could have gotten that large unless they were walking,” Janis said.

Today’s kangaroos hop at fast speeds and move about on all fours for slow speed travel (or, as a recent paper noted, “pentapedally,” which means on all fours plus the tail). This requires a flexible backbone, sturdy tail, and hands that can support their body weight. Sthenurines don’t appear to have had any of those attributes.

Whether any of the sthenurines still hopped to attain fast speeds, Janis said, bipedal walking was much more likely to be at least their mode of slow speed locomotion. Indeed, the researchers found multiple lines of evidence suggesting that sthenurines were much better suited than extant kangaroos to put their weight on one foot at a time, a requirement for walking. The only possible example of walking in living kangaroos, Janis said, are anecdotal reports of it in tree kangaroos.

Anatomy for ambling

The paper offers many examples of how sthenurines were anatomically ill-suited for hopping but well suited for bearing weight on one leg at a time.

Take, for one example, the evidence from the ankles of sthenurines. In walking and running animals such as horses and dogs, the lower end of the tibia has a flange that wraps over the back of the joint, providing extra stability to support more weight on each ankle. Living kangaroos, who almost always distribute their weight over both feet equally, don’t have that flange, but sthenurines did.

Sthenurines had proportionally bigger hip and knee joints. The shape of the pelvis differs importantly as well. The sthenurines had a broad and flared pelvis that would have allowed for proportionally much larger gluteal muscles than other kangaroos. Those muscles would have allowed them to balance weight over just one leg at a time, as do the large gluteals of humans during walking.

In much of their skeletons, the analysis showed, sthenurines were proportionally more “robust” (big-boned) than the rather slender-boned large living kangaroos.

In looking at overall kangaroo anatomy through history, Janis said, the analysis revealed that, if anything, the large kangaroos that are the “weird” ones are actually the living red and gray kangaroos, because they are proportionally very lightly built for their size (like cheetahs among cats).

Previous researchers had already observed that sthenurines’ hands were ill-suited for supporting the kangaroo for all-fours but were instead specialized for foraging. That also helps to rule out the idea that sthenurines would have gotten far on all fours or pentapedally.

And then there was Janis’ observation of the relatively inflexible spine, which has also noted by others. These and many other observations suggest that hopping or pentapedal locomotion would have been difficult, Janis said, but walking would not have been.

“If it is not possible in terms of biomechanics to hop at very slow speeds, particularly if you are a big animal, and you cannot easily do pentapedal locomotion, then what do you have left?” Janis reasoned. “You’ve got to move somehow.”

Whether the reliance on walking, which isn’t as fast as efficient or as suited for long distances as hopping, explains why sthenurines became extinct about 30,000 years ago is unknown, Janis said. They might have struggled to elude human hunters, she said, or they might have been unable to migrate far enough to find food as climate became more arid.

The hypothesis that sthenurines were walkers would still benefit from other lines of evidence, Janis acknowledged, such the discovery of preserved tracks.

But until that is found, the authors wrote, the balance of the anatomy shows that these roos were specialized — and sometimes sized — for walking, not for hopping.