PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Jacy Worth waited almost two years to receive her mother Margaret Larkin Jusyk’s ashes, but she took pride and comfort knowing that even after death her mother was still working to teach and to contribute to discovery.

During a long life before she donated her body to Brown University’s Anatomical Gift Program, Jusyk, who went by Peg, was never idle. In World War II she served in the Navy, flying on planes as a WAVES aerographer to provide weather data and to instruct colleagues. The Connecticut native earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees at the University of Bridgeport and Fairfield University, worked as a teacher and a school psychologist, and she assisted in pediatrics research at Yale. Between her degrees she worked on statistics for Dun & Bradstreet and mapping for the Pan Am airline. Jusyk was a pastel artist, an avid golfer, and a church, museum, and community volunteer whose services included protecting endangered piping plovers and visiting the homebound elderly. She was a participant in the famed Women’s Health Initiative medical study. Even after retirement she earned a real estate license and continued working.

“She had a quest for knowledge her entire life,” Worth said. “She was always very interested in science and the progress of science.”

To Worth, it didn’t seem surprising when Jusyk said she wanted to be an anatomy donor.

“I was sort of happy she was still working, still doing something,” Worth said. “I’m so proud of her. She was still useful. That’s how she always was.”

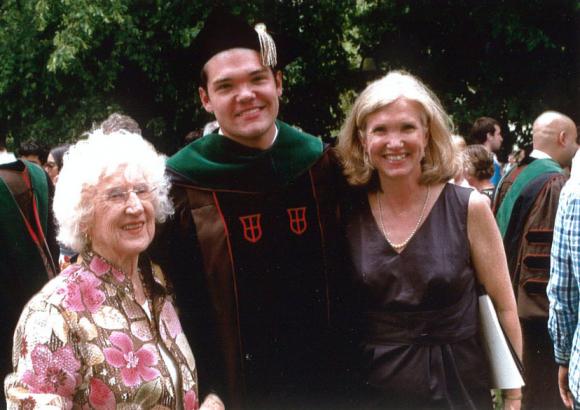

Margaret Jusyk, with daughter Jacy, capped a long life of service, discovery, and engagement by donating her body to medical education.

Worth and her husband Jim were among more than 40 family members of anatomical donors who gathered at Brown on the evening of August 14 at the invitation of the Warren Alpert Medical School Class of 2017. These were the students who in the last year, because of the contributions of the donors, gained the rigorous and intimate knowledge of the human body’s structure and complexity that a medical education requires.

“Our group thought it was important to include the families because they made a sacrifice in their loved one donating their body,” said student Samantha Roche, one of the organizers of the evening’s ceremony. This is the first year that students, who had before always reflected on their anatomy lab experiences in private, decided to invite the families. “It’s important for us to thank them, too. As much as the donors donated their bodies, these families have been waiting for their remains for quite some time.”

Worth, whose son Patrick graduated from the Alpert Medical School in 2011, said she’d often think of her mother during the two years her body was at Brown. She got her mother’s ashes back last spring — and soon after, an invitation to attend the ceremony.

“When I got this beautiful invitation to this, right away I wrote back to Amita [Kulkarni],” another student organizer. “I was delighted just because there was going to be a ceremony acknowledging their gift. These med students realized that there was more involved than just this body. It’s the family.”

Gratitude to the donors and their families was indeed the theme of the evening, made possible by support from the Brown Medical Alumni Assocation. The lessons the students learn from their donors’ bodies are fundamental to their training as doctors and will forever influence the care they give to every patient they treat.

“Each medical student in this room will see thousands, if not tens of thousands, of patients in his or her medical career,” student Allan Joseph told the audience. “No matter what field we choose to pursue we will rely on our anatomical knowledge in treating all of them. We would not have that knowledge without the Anatomical Gift Program. We medical students cannot thank the donors who gave such a gift to us, but we can thank their families and their friends for supporting them in that decision.”

Later in the ceremony Dr. Christine Montross, assistant professor of psychiatry and human behavior and an Alpert Medical School alumna, spoke. Her book Body of Work recounts her thoughts on her time in the anatomy lab directed then as now by senior lecturer Dale Ritter, who introduced her. Worth said Montross’s book likely provided some of the inspiration for Jusyk to donate her body.

Montross read two passages, including one in which she reflected on what her donor taught.

“The lessons her body taught me are of critical importance to my knowledge of medicine,” Montross read. “But her selfless gesture of donation will be my lasting example of how much it is possible to give a total stranger in the hopes of healing. That lesson, when I am called to treat critically ill patients who no longer appear human, and prisoners, and demented grandfathers who are dying and angry and scared, is the lesson I hope beyond all else to have absorbed.”

Student Norin Ansari, a co-organizer, said she reflected on the extraordinary gift of the donors when she viewed the “memory table” just outside the De Ciccio Family Auditorium in the Salomon Center for Teaching. There, family members placed the pictures and articles they brought to display about the donors.

“To see a man smiling proudly in uniform, to read about a centenarian reaching her milestone birthday, and to see a proud grandmother with her grandson — all of these really put into perspective that these people were just like you and me. But they must have also been very generous and kind souls to want to continue to be so helpful even after death,” Ansari said. “Prior to this, we had only known their ages, occupations, and cause of death.”

At the end of the ceremony, which also included student musical performances and a blessing and poetry reading from University Chaplain Janet Cooper Nelson, students crossed the stage as Roche read the first name and last initial of each donor. As the students crossed, they placed a white flower in a vase for each name.

Among those 43 names was “Margaret J.,” who like all the donors had provided of themselves a gift of education for the good of thousands. On that night, the students celebrated that gift with their donors’ loved ones.