PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — New research shows that people who grew up in a household where a member was incarcerated have a 18-percent greater risk of experiencing poor health quality than adults who did not have a family member sent to prison. The finding, which accounted for other forms of childhood adversity, suggests that the nation’s high rate of imprisonment may be independently imparting enduring physical and mental health difficulties in some families.

“These people were children when this happened, and it was a significant disruptive event,” said Annie Gjelsvik, assistant professor of epidemiology in the Brown University School of Public Health and lead author of the study published in the Journal of Healthcare for the Poor and Underserved. “That disruptive event has long-term adverse consequences.”

The study is based on data gathered from more than 81,000 adults who responded to the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey, a standardized national assessment of health. In 2009 and 2010, 12 states and the District of Columbia included questions about childhood adversity, including this question about the first 18 years of life: “Did you live with anyone who served time or was sentenced to serve time in a prison, jail or other correctional facility?”

The states were Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Tennessee, Washington in 2009 and Hawaii, Maine, Nevada, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Vermont, Washington, Washington D.C., and Wisconsin in 2010.

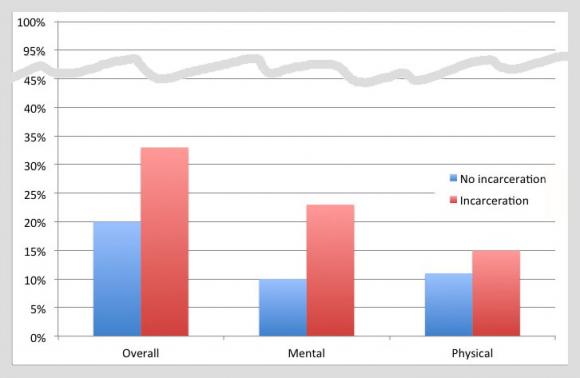

Gjelsvik and her co-authors analyzed the survey results to see if there were overall health quality differences between those who answered yes or no. In the survey, respondents were asked how many days out of the last month they experienced bad mental or physical health. If the total exceeded 14 days their overall health quality was considered poor.

Of 81,910 respondents 3,717, or 4.5 percent, said they grew up in a household where an adult family member was incarcerated. The proportion rose to 6.5 percent when the total sample was statistically weighted to accurately represent the adult population of each state. The percent of people exposed to an incarceration in the family varied markedly by age (younger people were more likely than older people), by race (blacks and Hispanics were more likely than whites) and by other demographic factors.

Because a number of problems in childhood and later in life can lead to poor health quality, the researchers employed statistical analysis techniques to account for, or factor out, potentially confounding influences including age, education (which was tightly correlated with income), and the total number of other adverse childhood experiences elicited in the survey. Those included emotional, physical, and sexual abuse as well as exposure to domestic violence, substance abuse, a mentally ill household member, and parental separation or divorce.

Even then, they found the 18-percent greater risk of poor adult health quality among those exposed to an incarceration in their family during childhood.

Last May, in a separate paper based on the same data, Gjelsvik’s team found that people with family incarcerations in their youth were more likely as adults to engage in smoking and heavy drinking, after controlling for demographics and additional adverse childhood events.

Gjelsvik acknowledged that the studies leave open questions because they did not measure which family member was sent to prison, when, for what reason, or for how long.

But the overall findings argue against sentencing policies such as mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent offenders, Gjelsvik said. Incarceration can be necessary, but greater appropriate use of alternatives to prison for nonviolent offenders, such as drug courts, could spare some innocent children from a lifetime of reduced health.

“I’m not saying don’t incarcerate people,” she said. “But we need to allow our system to use judgment and to use innovative and evidence-based programs.”

In addition to Gjelsvik, other authors are Dora Dumont, Rhode Island Department of Health; Amy Nunn, assistant professor of public health and medicine at Brown University; and Dr. David Rosen, research associate at the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill.

The National Institutes of Health supported the study (grant: P30AI50410).