PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — When landlords have followed Rhode Island’s law requiring them to protect tenants from exposure to lead, their compliance has significantly reduced blood levels of the toxic metal in children. But in four of the state’s major cities, only 20 percent of properties that are covered by the law were in compliance with the law even more than four years after it took effect, according to a study by researchers at Brown University, The Providence Plan, HousingWorks RI, and the Rhode Island Department of Health.

“The law works when it is followed,” said Michelle Rogers, a senior project analyst in the Brown University School of Public Health and lead author of the study to be published in the August issue of the American Journal of Public Health.

The sweeping study of the impact of Rhode Island’s Lead Hazard Mitigation Law, which took effect in November 2005, found that children living in compliant buildings between 2005 and 2009 had significantly lower blood lead levels than children in noncompliant ones. When the researchers looked at before-and-after test results of children whose buildings were brought into compliance, they found that their lead levels dropped by more than 17 percent on average.

That drop was enough to bring the average child in that sample from 5.2 micrograms per deciliter down to 4.3. That’s important because public health officials and physicians consider 5 micrograms to be a level of concern. Too much lead can harm the neurological development of young children.

The Rhode Island Department of Health mandates that children be screened for lead twice by 36 months and collects records through the Lead Elimination Surveillance System.

The study found that among all 16,043 non-exempt properties in Central Falls, Pawtucket, Providence, and Woonsocket, the owners of only 20.3 percent had earned the needed Lead Hazard Mitigation Certificates or met a higher standard. In properties where children lived between 2005 and 2009, the compliance rate was 29.7 percent.

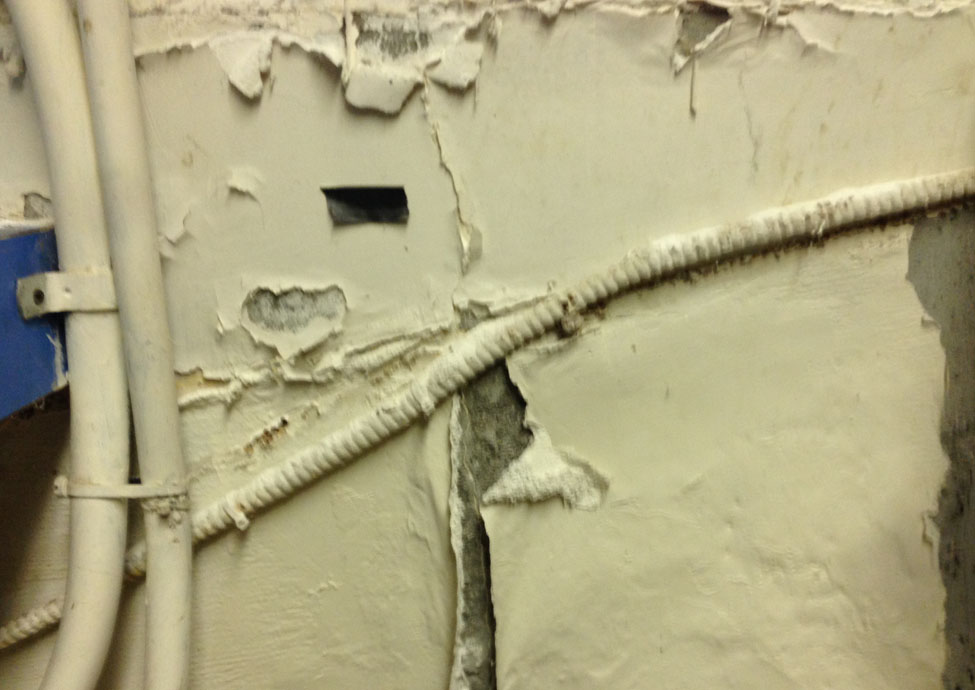

The law requires that landlords of non-owner-occupied buildings built before 1978 that have more than three units take a three-hour lead hazard awareness class, assess and fix any hazards to the property, perform lead-safe maintenance practices, and obtain the certificate from a proper inspector.

In many cases, Rogers said, repainting using commonsense work practices is enough to meet the law’s standard and keep children safe.

In many cases, Rogers said, repainting using commonsense work practices is enough to meet the law’s standard and keep children safe.

Still, because of the lack of compliance with the law and widespread exemptions, more than 20 percent of children in the four cities who live in dwellings without a certificate have had at least one test above the 5 microgram level, the study showed. One child in 30 in such homes has tested above 10 micrograms.

The average blood lead level among children in homes without a certificate is 3.3 micrograms per deciliter.

Exposure in exempt properties

The law exempts many dwellings, such as owner-occupied single-family homes. More than two-thirds of the residences in the four cities analyzed were therefore exempt from the law.

But the researchers looked at the blood tests of children living in those properties, and found that lead exposure is a problem there too, although somewhat less so. More than 20 percent of children living in exempt dwellings had at least one test above 5 micrograms, and 2.8 percent had a test above 10 micrograms, according to the study data.

The results prompted the authors to raise the question of whether the law should be expanded to all dwellings.

“There are so many properties that are exempt that young children are living in,” Rogers said. “They are still being exposed. For children to grow up healthy and ready to learn, we need stricter enforcement of the lead compliance regulations and legislation that covers all properties where children live.”

The study’s other authors are James Lucht, formerly of The Providence Plan, and Alyssa Sylvaria of the Providence Plan, Jessica Cigna of Housing Works RI, Robert Vanderslice of RIDOH, and Dr. Patrick Vivier of Brown University.

The study was supported by a grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to The Providence Plan.