PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — In U.S. cities, it’s not just what you do, but also your address that can determine whether you will get HIV and whether you will survive. A new paper in the American Journal of Public Health illustrates the effects of that geographic disparity – which tracks closely with race and poverty – and calls for an increase in geographically targeted prevention and treatment efforts.

“People of color are disproportionately impacted, and their risk of infection is a function not just of behavior but of where they live and the testing and treatment resources in their communities,” said lead author Amy Nunn, assistant professor (research) of behavioral and social sciences in the Brown University School of Public Health. “Limited health services mean more people who don’t know their HIV status and who are not on treatment. People who don’t have access to treatment are much more likely to infect others. Simply having more people in your sexual network with uncontrolled HIV infection raises the probability that you will come into contact with the virus. This is not just about behavior, this is about access to critical health services.”

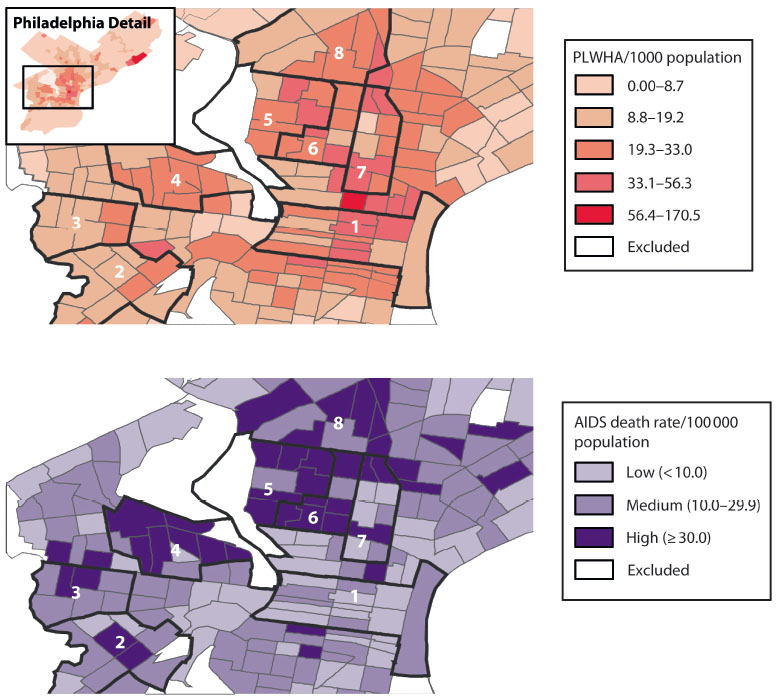

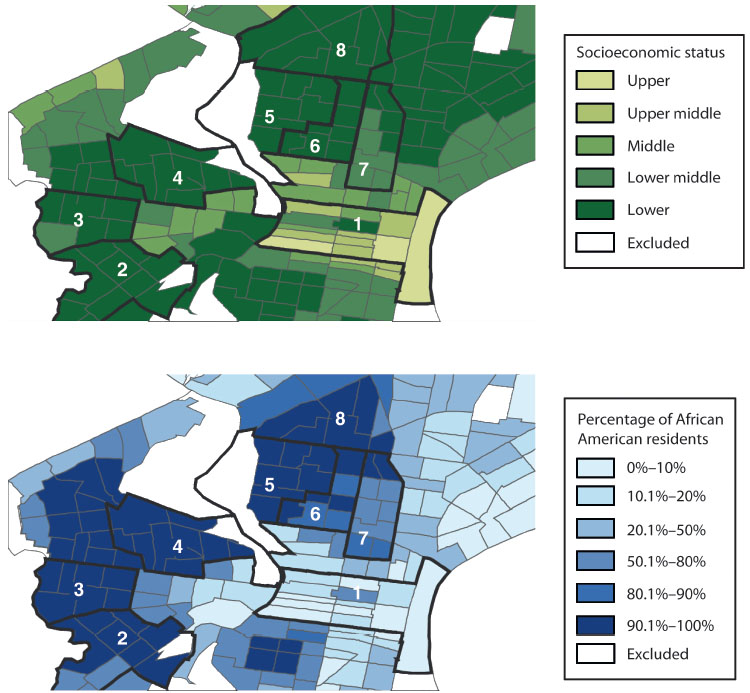

It’s no secret that the United States has economic disparities in access to health care, but the consequences of that for the HIV epidemic are laid bare in maps in the paper. They show that the nation’s epidemic has become concentrated in urban minority neighborhoods, where HIV incidence can be comparable to some countries of sub-Saharan Africa.

The high-incidence minority neighborhoods of New York and Philadelphia, the maps show, have a high death rate as well, even compared to simlarly high-incidence neighborhoods that are wealthier and whiter. The most likely difference between the communities, Nunn said, is in their access to testing, treatment, and care services.

Nunn and co-authors including Phill Wilson, president and CEO of the Black AIDS Institute, said federal and state public health efforts should recognize that geography contributes to HIV risk and focus greater efforts on targeting the most heavily impacted neighborhoods around the country. Instead, there has been less federal money for interventions outside of clinical settings.

“With the new surveillance tools available to us, we know where the epidemic is down to the census track or zip code,” Wilson said. “If we are serious about ending the AIDS epidemic in this country, we need to use those tools to invest in vulnerable communities. Unfortunately, instead of building infrastructure and expanding capacity in poor urban communities, we are dismantling the fragile infrastructure that exists.”

Early efforts

Aware of the need, many of the paper’s authors have helped put together neighborhood testing and treatment campaigns in recent years. The projects provide templates, they say, for engaging local communities through grassroots action and partnership with local institutions and media. These not only spread the word, but also reduce the stigma of openly confronting the disease. The authors also argue for a research and policy agenda that focuses on neighborhoods rather than solely on individuals for HIV intervention strategies.

An especially large effort, “The Bronx Knows,” led by the New York City Department of Health, brought together 75 local institutions and other partners between 2008 and 2011 to cover the entire New York City borough. The campaign, in part led by co-author Dr. Blayne Cutler, conducted more than 600,000 tests and confirmed 4,800 cases, including 1,700 that weren’t previously known. The percentage of local adults who reported having been tested rose to 80 percent from 72 percent and HIV positive residents linked to appropriate health care rose to 84 percent from 82 percent.

Since 2012 Nunn has led a privately funded project focused on Philadelphia’s 19143 zip code, one of the most heavily impacted neighborhoods of the country, called “Do One Thing.” Working with colleagues including co-author Dr. Stacey Trooskin of Drexel University, Do One Thing has partnered with local media and leaders including clergy, and sent volunteers door-to-door to promote HIV and HCV testing and treatment.

So far Nunn’s teams have tested more than 6,000 residents with an HIV rate of 0.7 percent. They simultaneously test for hepatitis C and have found that 5 percent of those who test are HCV positive. When people test positive for either virus, the teams immediately link them to health services and treatment.

Targeting testing and treatment

Other efforts of varying nature and scale are underway in San Diego, Oakland, Washington D.C., and Miami, but in the article the authors report that such campaigns are not yet enough to turn every tide that has flooded neighborhoods around the country with especially high degrees of infection and mortality.

More of the money granted to states and cities, for instance, could be targeted to the neighborhoods with highest infection rates and where testing and treatment have been most lacking.

“Many of our resources don’t go to the communities who need them most,” Nunn said. “But we know exactly where people live who are becoming infected. We have so many tools that we know are effective at fighting the epidemic. Not to provide them to the most heavily impacted communities is a social injustice. We should be rolling out testing and treatment services and positive social marketing messages en masse in these communities.”

In addition to Nunn, Wilson, Cutler and Trooskin, the paper’s other authors are Annajane Yolken of The Miriam Hospital, Dr. Susan Little of the University of California–San Diego, and Dr. Kenneth Mayer of Brown University, Harvard University, and the Fenway Community Health Center in Boston.

The National Institutes of Health, including the Lifespan Tufts Brown Center for AIDS Research, the California HIV Research Program, and Gilead Sciences HIV focus program provided support for the paper.