PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Dec. 6 was a dreary morning but the community room at Kennedy Manor on Clinton Street in Woonsocket, R.I., felt festive as residents shopped at the Live Well/Viva Bien produce market set up by researchers from the Brown University School of Public Health. A demonstration chef used the fruits and vegetables in omelets and to top French toast. Balloons floated in the air amid the sweet aroma of dozens of boxes of healthy food.

Anne Richer, a resident of the subsidized housing high-rise, bought apples, tomatoes, oranges, parsnips, carrots, a yam, and a yucca.

Richer said she particularly likes how fresh the produce typically is at the Live Well/Viva Bien markets.

“Usually I do a big shop at the beginning of the month when I get my food stamps. It’s hard to get vegetables that are going to keep, but these are very fresh,” Richer said. “They keep a long time.”

Kim Gans, research professor of behavioral and social sciences, leads the research, which asks whether providing convenient access to affordable fresh fruits and vegetables — along with educational campaigns, recipes and chef-led demonstrations — will increase produce consumption and improve health. With funding from the National Cancer Institute, she’s brought the markets to eight Rhode Island subsidized housing projects over the last three years and in a companion study called “Good to Go” has brought her “Fresh to You” markets to 16 worksites. The studies are randomized controlled trials with control groups (seven housing complexes and eight worksites) that don’t receive the markets. But even they benefit from the studies because they get free physical activity and stress reduction programs.

Ultimately Gans’ research could yield findings that result in Fresh To You also promoting health elsewhere, but because the study is local, it already brings fresh, affordable produce to Rhode Islanders like Richer and fellow shoppers Bob LaBelle and Eileen Tetreault every month. Gans is also studying whether Fresh to You can become a sustained nonprofit business model, providing not only local produce but also jobs.

It’s the nature of public health research and education to directly benefit the community. Terrie Fox Wetle, dean of the Brown University School of Public Health Dean, serves on statewide committees dedicated to implementing health reform and improving care. She says public service is part of the school’s core mission. When Brown elevated what was once a program to the status of a school in July, it opened the door for greater research and teaching growth and therefore more of that community impact to occur.

It’s also the nature of public health, she says, that those expanded efforts will mean that “nothing” happens more often than before.

“One of the challenges of public health is that you’re a success when nothing happens,” Wetle said. “You’re a success when people don’t get heart disease because there is an exercise program for kids in the community or they don’t get lung disease because there’s no smoking. It takes a whole lot of effort to make nothing happen.”

The school is replete with examples. In many different ways, all over the state, Brown public health faculty members, students and staff are doing good by doing research.

In the neighborhood

Two recently concluded projects demonstrate that research can have a direct impact in the community, especially because public health researchers often work together with colleagues in state government.

Beginning in 2006, for instance, Patrick Vivier, professor of health services policy and practice and professor of pediatrics in the Alpert Medical School, joined forces with Patrick Lynch, Rhode Island’s attorney general at the time, to guide the remediation of lead paint in 600 homes as part of an out-of-court settlement with the chemical giant DuPont.

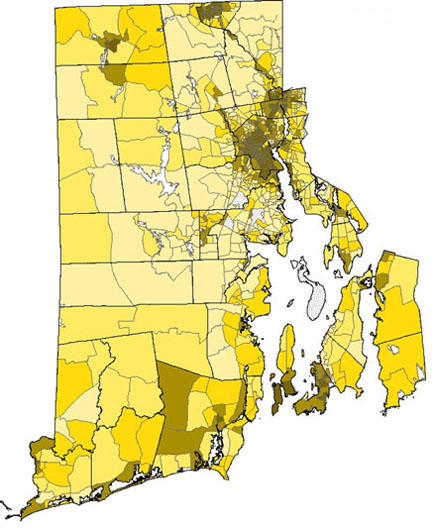

Vivier and his team used their expertise to create a detailed map showing where Rhode Island had the highest lead exposure risk. They used inputs such as rates of high blood levels of lead, the age of housing stock, and the incomes of local residents to pinpoint the most critical areas for cleanup. That set the stage for remediation efforts that continued into 2011.

The maps Vivier’s team produced showed striking geographic and demographic disparities. Now he’s continuing to investigate other important health risk factors that come about from where people live in Rhode Island.

“We are not only trying to publish in journals and be on the cutting edge of public health research but also figure out how that work can simultaneously help here in Rhode Island,” Vivier said.

In the same vein, Patricia Nolan, former director of the Rhode Island Department of Health who teaches in the school and heads the Rhode Island Public Health Institute housed at Brown, recently led teams of students and community workers in doing more than 1,000 door-to-door interviews about health in neighborhoods of Providence, Central Falls, and Woonsocket. Together with Robert Marshall, clinical associate professor of health services, policy and practice, she sought to augment RIDOH’s statewide landline phone-based tracking of health risk behaviors. Their hypothesis was that to understand the specific risks to health in poorer neighborhoods, one has talk to residents in person.

By canvassing 547 residents and making careful observations in five neighborhoods on the South Side and West End of Providence, the team found relatively elevated rates of high blood pressure and diabetes and unsafe streets, few green spaces, and impassable sidewalks. It therefore seems predictable that more than half of respondents didn’t get the recommended level of exercise. In Central Falls, 30 percent of 311 adults surveyed reported fair or poor health, compared to only 11.5 percent across Rhode Island’s cities overall.

“The level of reporting of poor health was quite stark in some of these neighborhoods,” Nolan said.

The data set not only helped to refine RIDOH’s data on health risks, Nolan said, but also has helped community groups such as the YWCA in Woonsocket and Progreso Latino in Central Falls in their efforts to target community services more effectively.

Fewer emergencies

Read about her 911 thesis project.

In a new collaboration with RIDOH, Brown environmental epidemiologist Greg Wellenius is pursuing a very different concern of Rhode Island geography. He’s helping the department plan for the potential health risks of global warming.

“The notion is that now climate change is unavoidable,” Wellenius said. “We’ve got to figure out how we are going to adapt communities to better prepare so that we can lessen the health effects of climate change.”

The overall project, funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, is a big undertaking at RIDOH. Wellenius is focused on whether an increase in hot days is likely to drive more people to emergency rooms. He’s analyzing data on how heat and emergency visits correlate while also accounting for underlying seasonal variations in hospitalizations and other tricky statistical confounders.

State policymakers will be able to use his analysis to decide how to prevent a run on hospitals on hot days. They might decide to invest more in cooling centers, for example, or modify the temperature that triggers heat-related health advisories. (He’s finding that people start having trouble at about 75 degrees.)

To better understand current emergency calls, Michael Mello, associate professor of emergency medicine, and masters student Chenelle Norman are working with RIDOH too. They are investigating why some elderly Providence residents make especially frequent use of the 911 system. The understanding they generate will then be used to devise preventive interventions to help those residents live more safely and healthfully. The project’s funding from the Irene Diamond Fund, Wetle notes, depended on the University establishing its School of Public Health.

Chronic conditions

Public Health prevention research is benefitting Rhode Islanders in other immediate ways, even for longer-term problems. Researchers in Brown’s Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies have been working for three decades to improve treatments for problems such as smoking and excessive drinking. In that time they’ve worked with untold thousands of community residents.

Rhode Islanders interested in quitting smoking, for example, need look no further than the website Quit With Brown. It features three studies underway at Brown that are recruiting hundreds of people and provides links to many other quitting resources, said Chris Kahler, professor and chair of the Department of Behavioral and Social Sciences.

Kahler himself just wrapped up testing a smoking cessation treatment with a hundred volunteers. He’s now analyzing his data on whether positive psychology – an intervention that encourages a positive mood for the prospective quitter – is more effective than standard treatment. As in Gans’ studies, whether volunteers are enrolled in the experimental condition or the control group, they get a treatment that can help.

“The standard that we’re always trying to beat is a very high standard of a very good smoking cessation approach,” Kahler said. “We’re trying to improve on that to see if we can do better than the best that’s out there.”

Elsewhere in Kahler’s department, other professors are leading research focused on different kinds of long-term disease prevention. Akilah Dulin Keitah, for example, is working with the Center for Southeast Asians in Providence to identify perceived risks for — and protective factors against — childhood obesity in the Southeast Asian communities. The goal of the research, funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, is to develop culturally appropriate interventions to improve health.

In academia, the idea of applying research to deliver a benefit is called translation.

“We provide service by translating the new knowledge that we develop through research into improved public health practice,” Wetle said. “It’s all focused on the health of the population.”