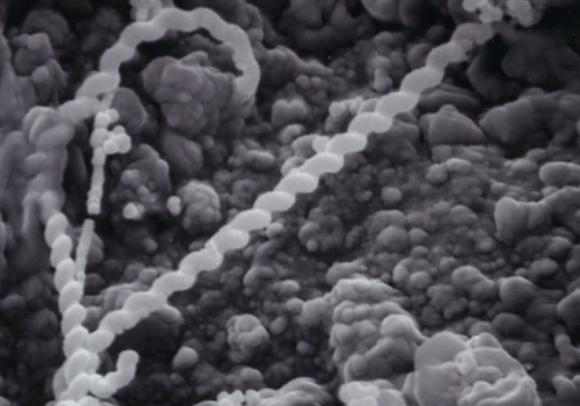

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — A high-angle helix helps microorganisms like sperm and bacteria swim through mucus and other viscoelastic fluids, according to a new study by researchers from Brown University and the University of Wisconsin. The findings help clear up some seemingly conflicting findings about how microorganisms swim using flagella, helical appendages that provide propulsion as they rotate.

Simple as single-celled creatures may be, understanding how they get around requires some complex science. The physics of helical swimming turns out to be “a really interesting fluid dynamics problem,” said Thomas Powers, a professor of engineering and physics at Brown and one of the new study’s authors.

At the scale of a single cell, fluids become much more viscous than on larger scales. A bacterium swimming through water “would be like us trying to swim in tar,” Powers said. That means swimming at the micron scale is a completely different enterprise than it is for fish or people. Counterintuitive as it may sound, tiny helical swimmers rely exclusively on drag to move forward. The turning flagellum creates an apparent wave that propagates out from behind the creature. The drag force against that wave pushes the creature in the opposite direction.

In recent years, there has been some theoretical work aimed at fully understanding the physics of this kind of swimming, much of it done by modeling how helical swimmers behave in water. But bacteria and sperm spend a lot of time in fluids like mucus and cervical fluid — fluids that are not only more viscous than water, but also elastic since they are full of springy polymers. Because a rotating helix might be able to push against the polymers, it could be that a viscoelastic fluid makes swimming easier.

“It’s a fairly simple question,” Powers said. “Does viscoelasticity make microorganisms swim faster or slower?” Finding the right answer, however, hasn’t been so simple.

Early theoretical work suggested viscoelastic fluids should slow helical swimmers down. But some experimental work in the Brown School of Engineering by Powers, postdoctoral associate Bin Liu, and Kenneth Breuer, professor of engineering, suggested that viscoelastic fluids should actually help helical swimmers move faster.

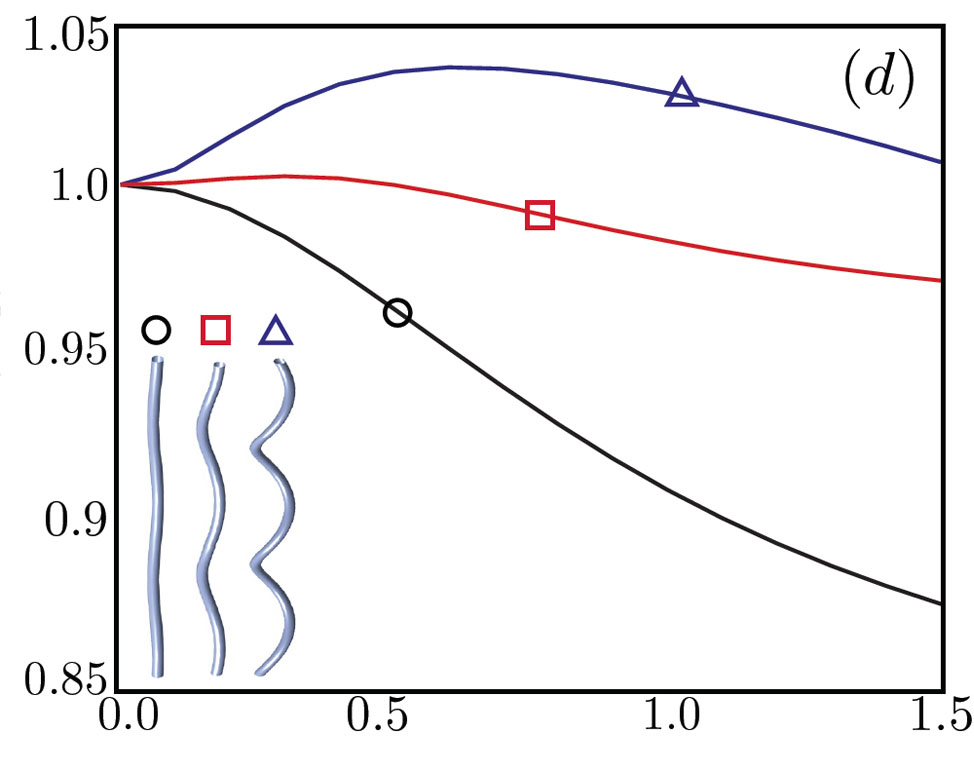

This latest study, published in the journal Physical Review Letters, helps to bridge that apparent gap. Powers and Liu worked with Saverio Spagnolie, aprofessor of mathematics at the University of Wisconsin and aformer postdoctoral researcher at Brown. Using what Powers described as “some clever numerical methods and a lot of hard work,” Spagnolie was able to show computationally that the pitch angle of the helix — the degree to which the helix is coiled — matters in how well it performs in viscoelastic fluids. At a low pitch angle (think of a stretched phone cord), helices move more slowly in viscoelastic fluids. When the pitch angle increases, performance improves.

The findings reconcile the experimental and earlier theoretical work. Much of the theoretical work, which suggested more viscosity would cause slower swimming, assumed a small pitch angle for the sake of keeping the computations manageable. The experimental work, which showed viscosity sped swimming, involved higher pitch angles. By showing numerically that a higher pitch angle increases speed, the researchers were able to explain that apparent discrepancy. “This work shows how you can connect that prior work,” Powers said.

While this work was extremely valuable in linking theory and experiment, there’s still much more work to be done on this problem, Powers says. “We don’t really understand the result because it is so hard to visualize the three-dimensional configuration of all the forces involved. It’s actually very frustrating. We’re still trying to get an intuitive picture.”

That, at this point, is still an upstream swim.

Ultimately, the researchers say, a better understanding how tiny swimmers get around could inform studies of bacterial infection and fertility. It could also help scientists develop artificial swimmers that could deliver medicine inside the body.

The work was supported by the National Science Foundation (CBET-0854108).