PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — A new study in the journal Cancer that tracked survival during the last decade of more than 2,200 adults with a highly aggressive form of lymphoma finds that with notable exceptions, medicine has made substantial progress in treating them successfully. To help doctors and researchers better understand who responds well to treatment and who doesn’t, the study authors used their findings to create a stratified risk score of patient prognosis.

Burkitt lymphoma is not a common lymphoma but it is especially aggressive. The apparent progress doctors have made during the last two decades has come, unlike with many other cancers, with little guidance about how to treat different patients or what outcomes to expect. The same regimen of intensive chemotherapy and the monoclonal antibody rituximab are recommended for most patients.

“There was little available for Burkitt lymphoma in terms of prognostic factors, indicators, or scoring,” said Dr. Jorge Castillo, assistant professor of medicine at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University and a hematology/oncology specialist at Rhode Island Hospital. He is the lead author of the study, which first appeared online July 30.

Castillo wanted to understand the prognosis of patients better, so he and his co-authors looked at 11 years of patient records in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, which keeps patient demographic and outcomes data from 18 areas around the country. They analyzed survival rates among 2,284 patients by factors including age, race, stage of the cancer at diagnosis, and in what region of the body the cancer struck.

What they found is that while survival rates have risen substantially overall, outcomes have not improved much for patients who are older than 60, black, or whose cancer is diagnosed at a late stage. They used these risk factors to create a simple new risk score that allowed them to make meaningful distinctions about prognosis. Patients with the lowest score had a better than 7 in 10 chance of survival with treatment, while those with the highest score have a less than 3 in 10 chance of surviving.

Improved survival, for most

Age makes a big difference in survival, Castillo and his co-authors found. Their analysis yielded the calculation that patients over 80 years old have nearly five times the risk of dying from the cancer as people aged 20-39. Patients aged 60-79 had twice the risk of dying as the youngest patients and those aged 40-59 had a risk 1.5 times greater than those aged 20-39.

Risk of death climbed similarly with the stage of cancer. Stage IV patients had a 2.4 times greater risk of dying than those at Stage I. Stage III patients had a 1.5 times greater risk.

Race was also a factor, although to a lesser degree. Hispanics and whites had similar risk levels but black people, who accounted for 9.3 percent of the patients, had a 1.6 times higher risk of death.

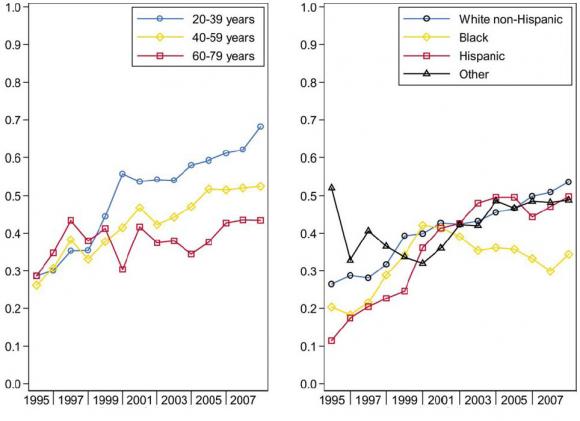

These same risk factors are also evident in whether patients have seen improved survival over time, for instance as intensive chemotherapy and later rituximab have gained prevalence.

In 1998, the survival rate was fairly uniform for all age groups, Castillo and his colleagues found: 34.7 percent overall. As of 2007, survival had risen to 62.1 percent for the youngest adult patients, but patients over 60 have drifted only slightly upward to a survival rate of 43.5 percent.

Among patients of different ethnic backgrounds, there is a similarly widening gap: Survival among non-Hispanic whites rose from 31.7 percent to 50.9 percent and among Hispanics from 22.7 percent to 47.1 percent. Among blacks, however, survival has remained low and flat: from 28.8 percent in 1998 to 29.9 percent in 2007.

Castillo said he does not know with certainty from the study or from the medical literature why blacks fare relatively poorly, but in his study he was able to control for socioeconomic status and the disparity in survival rates was independent of socioeconomic status.

Prognostic score

Using the significant risk factors they discovered, Castillo and co-authors Dr. Eric Winer, also of RIH, and Dr. Adam Olszewski of Memorial Hospital in Pawtucket created the risk score in which being 40-59 years old or being black adds one point, being age 60 to 79 or having a stage III or IV diagnosis adds two points, and age over 80 adds four points. Doing so separated the 2,284 patients into roughly equal groups with a wide range of five-year relative survival rates (relative to the likelihood of survival of a similar person without the disease).

Among the groups, those with a score of zero to one had a 71 percent relative survival rate. A score of two reduced the rate to 55 percent, a score of three had a 41 percent relative survival. For those at a score of four or higher the relative survival rate was only 29 percent.

Castillo said there are several applications for the score, including helping doctors, patients and their families understand what to expect and to evaluate whether intensive regimens of difficult therapy are truly desirable, compared to possible alternatives. The score can also inform researchers about how to design clinical trials of treatments of the disease.

“It helps to identify people who don’t benefit from what we’re doing right now,” he said.

But thankfully for many people, care appears to be working.