PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — When heart attack patients present in the emergency department with some degree of anemia, or anemic patients have a heart attack, physicians have a tendency, but not much guidance, about whether to provide a blood transfusion. The idea is that a transfusion could help more oxygen get to the heart. Recent national guidelines suggested that there simply isn’t good evidence to encourage or discourage the common practice, but a new meta-analysis of 10 studies involving more than 203,000 such patients comes down on the side of it increasing the risk of death.

The next step for determining when the practice could be appropriate needs rigorous randomized trials that will generate more decisive, high-quality data, said lead author Dr. Saurav Chatterjee, a cardiology fellow at the Alpert Medical School of Brown University and the Providence VA Medical Center.

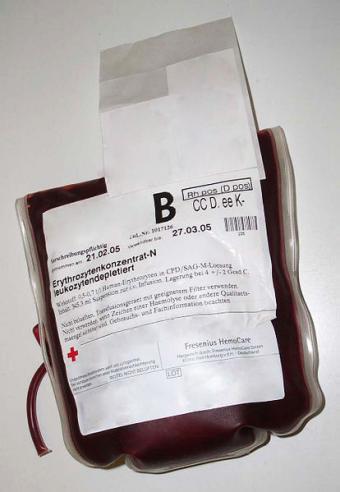

For the analysis published Dec. 24 in the Archives of Internal Medicine, Chatterjee and his co-authors combined and analyzed data from studies in which anemia patients with heart attacks either received “liberal” transfusions or received more restricted versions of the treatment or no transfusions at all. Liberal transfusions were defined as cases in which patients either received two units of blood or more or had a transfusion even with a hematocrit reading (a measure of red blood cell concentration) higher than 30 percent (normal is in the low 40s).

What the researchers found, after statistical adjustments to control for important medical factors, was that the risk of death was 12 percent higher for people who received the liberal transfusions than those who did not. Moreover, the group that received liberal transfusions had twice the odds of having another heart attack.

“What we found is that the possibility of real harm exists with transfusion,” Chatterjee said. “It is practiced in emergency departments all across the United States. I think it is high time that we need to answer the question definitively with a randomized trial.”

Of the 10 papers that Chatterjee and his co-authors reviewed, all but one were observational studies. The only randomized trial was a small pilot experiment.

Searching for an answer

Chatterjee began the study when he was a resident at Maimonides Medical Center in New York. He noticed a paper by the AABB (formerly the American Association of Blood Banks) in which the association said there was not enough clinical evidence for or against transfusions in heart attack patients.

For clinicians, the practice has always been a tough judgment call. Some transfusions are clearly necessary, for example when a patient’s troubles include not just a heart attack but also severe ongoing bleeding, Chatterjee said. But transfusions also create health risks, such as an increase in potential clotting because platelets may clump together more, or from an inflammatory immune response to the introduction of blood of a “foreign” source into the body.

Chatterjee and his co-authors decided to comb the literature to determine whether, if properly combined and analyzed, existing data could provide some insight. They found 729 potentially relevant studies, but only 10 that had the right data to help answer the question.

Few as they were, Chatterjee said, the studies all told much the same story.

“One of the things that struck us is that there were very few studies in evidence of transfusion at all,” Chatterjee said. “In our case, though, we found that the effect was pretty consistently harmful across the spectrum of studies, spectrum of time, and spectrum of patients that were enrolled in the individual studies.”

Chatterjee said the study should not be taken to mean that transfusions should be stopped altogether for anemic heart attack patients. Instead, he said, doctors must continue exercising their clinical judgment, at least until results from a large, well-designed randomized trial can be produced. Mindful of the risk his study found, however, they might just want to shift their thinking about where the border is among borderline cases.

“Before a definitive trial is out there, we should be conservative, especially considering the high risk of harm,” he said.

In addition to Chatterjee, the paper’s other authors are Jorn Wetterslev of the Centre for Clinical Intervention Research in Copenhagen, Denmark; Abhishek Sharma and Edgar Lichstein of Maimonedes Medical Center; and Debabrata Mukherjee of Texas Tech University.