PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Red, green, and blue lasers have become small and cheap enough to find their way into products ranging from BluRay DVD players to fancy pens, but each color is made with different semiconductor materials and by elaborate crystal growth processes. A new prototype technology demonstrates all three of those colors coming from one material. That could open the door to making products, such as high-performance digital displays, that employ a variety of laser colors all at once.

“Today in order to create a laser display with arbitrary colors, from white to shades of pink or teal, you’d need these three separate material systems to come together in the form of three distinct lasers that in no way shape or form would have anything in common,” said Arto Nurmikko, professor of engineering at Brown University and senior author of a paper describing the innovation in the journal Nature Nanotechnology. “Now enter a class of materials called semiconductor quantum dots.”

The materials in prototype lasers described in the paper are nanometer-sized semiconductor particles called colloidal quantum dots or nanocrystals with an inner core of cadmium and selenium alloy and a coating of zinc, cadmium, and sulfur alloy and a proprietary organic molecular glue. Chemists at QD Vision of Lexington, Mass., synthesize the nanocrystals using a wet chemistry process that allows them to precisely vary the nanocrystal size by varying the production time. Size is all that needs to change to produce different laser light colors: 4.2 nanometer cores produce red light, 3.2 nanometer ones emit green light and 2.5 nanometer ones shine blue. Different sizes would produce other colors along the spectrum.

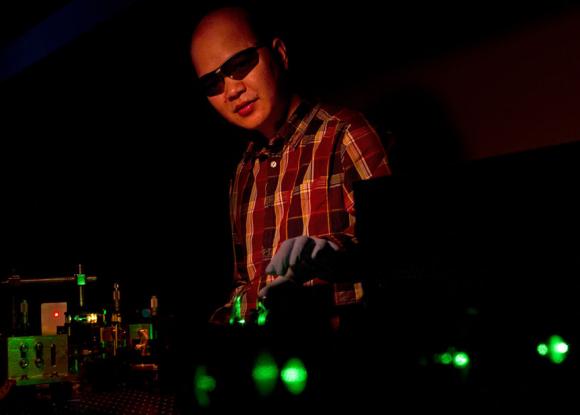

The cladding and the nanocrystal structure are critical advances beyond previous attempts to make lasers with colloidal quantum dots, said lead author Cuong Dang, a senior research associate and nanophotonics laboratory manager in Nurmikko’s group at Brown. Because of their improved quantum mechanical and electrical performance, he said, the coated pyramids require 10 times less pulsed energy or 1,000 times less power to produce laser light than previous attempts at the technology.

Quantum nail polish

When chemists at QDVision brew a batch of colloidal quantum dots for Brown-designed specifications, Dang and Nurmikko get a vial of a viscous liquid that Nurmikko said somewhat resembles nail polish. To make a laser, Dang coats a square of glass — or a variety of other shapes — with the liquid. When the liquid evaporates, what’s left on the glass are several densely packed solid, highly ordered layers of the nanocrystals. By sandwiching that glass between two specially prepared mirrors, Dang creates one of the most challenging laser structures, called a vertical-cavity surface-emitting laser. The Brown-led team was the first to make a working VCSEL with colloidal quantum dots.

The nanocrystals’ outer coating alloy of zinc, cadmium, sulfur and that molecular glue is important because it reduces an excited electronic state requirement for lasing and protects the nanocrystals from a kind of crosstalk that makes it hard to produce laser light, Nurmikko said. Every batch of colloidal quantum dots has a few defective ones, but normally just a few are enough to interfere with light amplification.

Faced with a high excited electronic state requirement and destructive crosstalk in a densely packed layer, previous groups have needed to pump their dots with a lot of power to push them past a higher threshold for producing light amplification, a core element of any laser. Pumping them intensely, however, gives rise to another problem: an excess of excited electronic states called excitons. When there are too many of these excitons among the quantum dots, energy that could be producing light is instead more likely to be lost as heat, mostly through a phenomenon known as the Auger process.

The nanocrystals’ structure and outer cladding reduces destructive crosstalk and lowers the energy needed to get the quantum dots to shine. That reduces the energy required to pump the quantum dot laser and significantly reduces the likelihood of exceeding the level of excitons at which the Auger process drains energy away. In addition, a benefit of the new approach’s structure is that the dots can act more quickly, releasing light before Auger process can get started, even in the rare cases when it still does start.

“We have managed to show that it’s possible to create not only light, but laser light,” Nurmikko said. “In principle, we now have some benefits: using the same chemistry for all colors, producing lasers in a very inexpensive way, relatively speaking, and the ability to apply them to all kinds of surfaces regardless of shape. That makes possible all kinds of device configurations for the future.”

In addition to Nurmikko and Dang, another author at Brown is Joonhee Lee. QD Vision authors include Craig Breen, Jonathan Steckel, and Seth Coe-Sullivan, a company co-founder who studied engineering at Brown as an undergraduate.

The US. Department of Energy, the Air Force Office for Scientific Research, and the National Science Foundation supported the research. Dang is a Vietnam Education Foundation (VEF) Scholar.