PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — People typically say they are invoking an ethical principle when they judge acts that cause harm more harshly than willful inaction that allows that same harm to occur. That difference is even codified in criminal law. A new study based on brain scans, however, shows that people make that moral distinction automatically. Researchers found that it requires conscious reasoning to decide that active and passive behaviors that are equally harmful are equally wrong.

For example (see below), an overly competitive figure skater in one case loosens the skate blade of a rival, or in another case, notices that the blade is loose and fails to warn anyone. In both cases, the rival skater loses the competition and is seriously injured. Whether it is by acting, or willfully failing to act, the overly competitive skater did the same harm.

“What it looks like is when you see somebody actively harm another person that triggers a strong automatic response,” said Brown University psychologist Fiery Cushman. “You don’t have to think very deliberatively about it. You just perceive it as morally wrong. When a person allows harm that they could easily prevent, that actually requires more carefully controlled deliberative thinking [to view as wrong].”

In a study published in advance online in the journal Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, Cushman and his co-authors presented 35 volunteers with 24 moral dilemmas and lapses like the one involving the figure skaters. For specific lengths of time the volunteers would read an introduction to the incident, a description of the character’s moral choices, and a description of how the character behaved. Then they’d rate the moral wrongness of the behavior on a scale from 1 to 5. All the while, Cushman and his co-authors, who were at Harvard University at the time, tracked the blood flow in the volunteers’ brains with functional magnetic resonance imaging scans.

Cushman expected to confirm what he had observed in behavioral experiments and published in 2006: that people employed conscious reasoning to arrive at the usual feeling, which is that actively caused harm is morally worse than the passively caused harm.

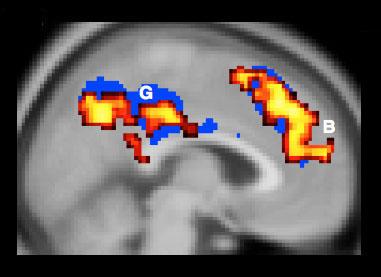

Figuring he had a clever way to prove it physiologically, he and his team compared the brain scans of people who judged active harm to be worse than passive harm to the scans of people who judged them as morally equal. His assumption was that those who saw a moral difference did so by explicit reasoning. Such people should therefore have exhibited greater activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex than those who saw no moral distinction. But to Cushman’s surprise, the greater levels of DPFC activity lay with those who saw active harm and passive harm as morally the same.

“The people who are showing this distinction are actually the ones who show the least evidence of deliberative, careful, controlled thinking,” he said, “whereas the people who show no difference between actions and omissions show the most evidence of careful deliberative controlled thinking.”

Social judgment

Cushman emphasized that his research does not suggest which moral judgment is right. But it is notable that our legal system enshrines the belief that active harm is worse than passive harm.

As one example, he cites a 1997 U.S. Supreme Court decision (Vacco v. Quill) in which the court ruled that given explicit permission from a patient, a doctor cannot directly euthanize the patient, such as with an overdose of morphine, but the doctor can follow a patient’s directive to cease life support or other treatment. In the case, the district court in New York initially ruled the way the Supreme Court ultimately did, but the appeals court in between ruled that euthanasia and ending life support were essentially the same.

Cushman said his new findings may be useful because they describe the mechanisms underlying how they, and perhaps society in general, arrive at moral judgments. Drawing on the metaphor offered by authors Max H. Bazerman and Ann E. Tenbrunsel in their ethics book Blind Spots, he suggests that the extra thought required to judge passive harm as morally wrong might be analogous to a blind spot.

Much as drivers learn to look over their shoulder before changing lanes, he said, people may want to examine how they feel about passive harm. Especially in specific, real-life situations, they may still conclude that active harm is worse, but they’ll at least have compensated for the automatic bias his research suggests is there.

In addition to Cushman, other authors include Dylan Murray, Shauna Gordon-McKeon. Sophie Wharton, and Joshua Greene. The research was supported by the Arete Initiative and the National Science Foundation.

Full example: Active or passive

Setup

Kelly is a figure skater trying out for the Olympics. The final spot on the team will go to either her or Jesse, depending on the outcome of a competition. When Kelly goes to the pro shop to pick up her skates, she sees Jesse’s skates lying on the counter.

Harmful act

- Kelly realizes that she could loosen the screws on Jesse’s skates, causing her to fall during the competition and lose. It is likely that Jesse would also seriously injure herself during the fall.

- Kelly loosens the screws on Jesse’s skates. Sure enough, Jesse falls during the competition and Kelly makes the team. Jesse also severely injures herself.

Harmful omission

- Kelly sees that the screws are loose on Jesse’s skates, which will cause her to fall during the competition and lose. It is likely that Jesse would also seriously injure herself during the fall.

- Kelly doesn’t warn anybody about the loose screws. Sure enough, Jesse falls during the competition and Kelly makes the team. Jesse also severely injures herself.