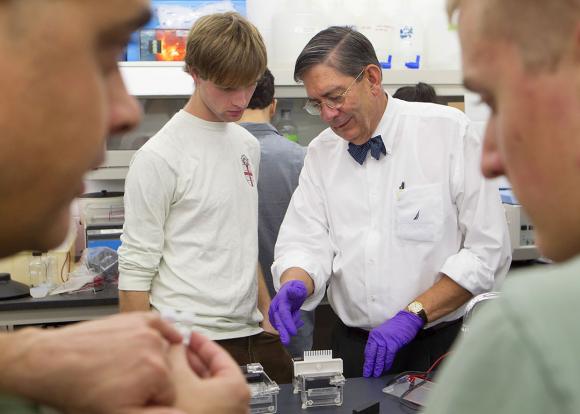

Up against a deadline, about 20 freshmen race around the lab and jostle politely to use the equipment like cooks in a café kitchen during the lunch rush. A professor, darting past in his own hurry to help one of them, makes a quip about “organized chaos.”

Like many of her peers, Aisha Ferrazares of Berkeley, Calif., is wielding a pipette in the quick but careful way that chefs wield their knives. But instead of pots and pans, she hovers over tiny plastic vials that hold the DNA of something no one has ever seen before: her very own species of phage, a virus named Virgil that lab partner Alex Hadik dug out of the campus soil at the beginning of the semester.

“In this class, everybody’s in different places at different times,” Ferrazares said. “If one day doesn’t go well you have to catch up the next day and it means often doing two or three processes at a time. You have to get really good at multitasking and budgeting your time.”

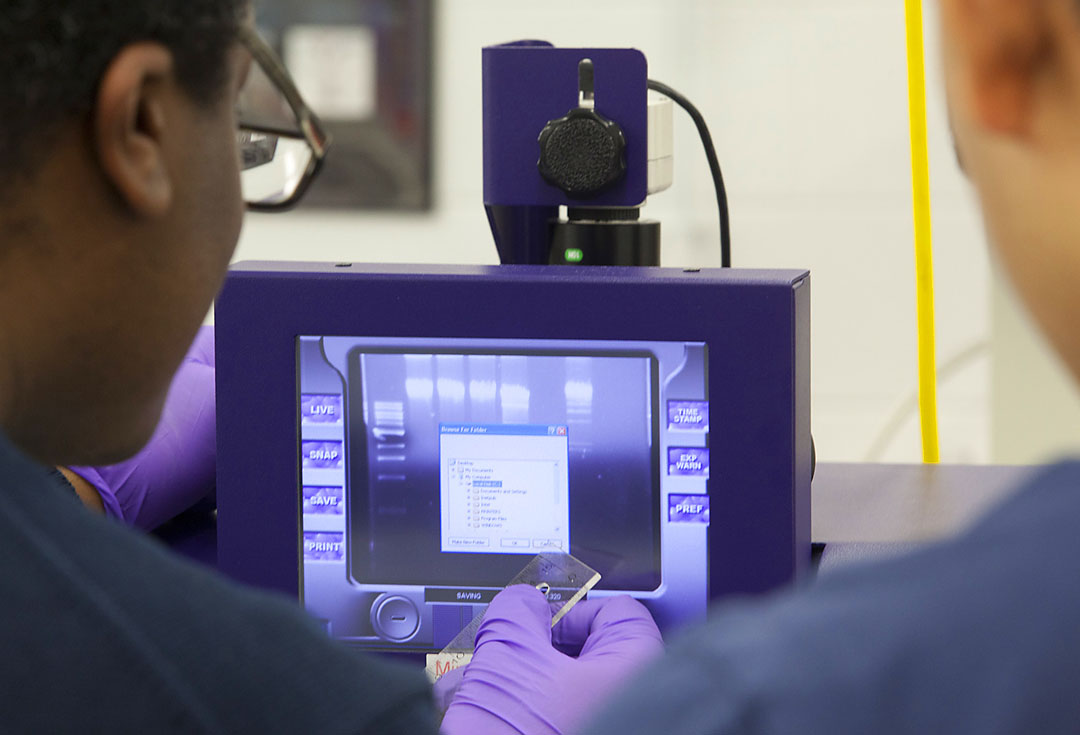

Ferrazares has thrust some vials of Virgil’s DNA into crushed ice, and has sent some for a twirl in the “mini spin” centrifuge. Her goal for the early afternoon on this dreary mid-November day is to get Virgil’s DNA into shape for analysis so that it can compete in the class’s “Olympics” at the next session. Among the 18 unique microbes the class has discovered, including Antina, Promuelos, Artemis, and Phelix, the winner of a secret ballot by the class will be sent to Maryland for the honor of having its DNA fully sequenced between semesters.

The yearlong “Phage Hunters” class is not the typical college freshman biology lab. There are no thoroughly scripted exercises meant to be followed to the letter toward a known outcome. Instead the class offers an open-ended process of genuine discovery and teaches skills many of the students normally wouldn’t learn for years. The hope, both of the class’s faculty and the funder, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, is that Ferrazares, Hadik, and their classmates will gain a sustained excitement about and love for science that few students gain from poring over an introductory textbook.

“There may be a publication if we’ve isolated something that’s really unique,” said Peter Shank, professor of medical science and one of the class instructors. “This is how science operates. We hope it will make them interested in science.”

From what the students say, and the buzz of motivation in the room, it seems to be working. They are clearly excited to have not only discovered new microbes, but also to examine their DNA. Soon they’ll look at them under electron microscopes. Next semester they’ll analyze the DNA on computers, getting a crash course in the red-hot field of bioinformatics.

“That’s where science is moving now,” Shank said. “That’s a whole other set of skills that will be unique for freshmen to have.”

Anthony Cox, a freshman from Atlantic City, N.J., recognized that the class would give him head start on the variety of the skills he wants to have as an aspiring biomedical engineer and physician. Older friends at other colleges didn’t get this chance.

“A lot of my friends in college don’t get a lot of lab time until their junior and senior year,” said Cox, who shares shares the phage “Antina” with his lab partner Tina Voelcker of Porto Allegre, Brazil. “I haven’t told most of them, but some of them say, ‘Really? That seems pretty neat. Tell me about what you are doing.’”

HHMI, which has funded other innovative biology programs at Brown for years, selected the University along with 11 other schools around the country last spring for the Phage Hunters program, which is part of its Science Education Alliance. About 40 schools have taken part over the last few years. This year, Providence College is an associate member.

It wouldn’t be fair to say that Selen Senocak came all the way from Istanbul for this class, but she was clearly glad to be there. She’s pre-med and is interested in either biology or neuroscience.

Not long after she reached American soil, she started digging it up. Senocak found her phage Artemis, named for the main character in book she is reading in another class, in the soil under a tree next to a sprinkler near the Ratty.

As she describes how she is preparing a DNA sample for analysis, she confesses that this isn’t Artemis’s first run through the machine. The first time her sample didn’t look so good. This second run will tell her whether there was something wrong with the how the last sample was prepared, or whether there was perhaps something lacking about the DNA sample.

She draws a millionth of a liter of the DNA solution into a pipette and adds some blue dye. Then she explains what makes digging in the mud and moving miniscule drops of liquid around so much fun.

“It feels very professional,” she said. “We’re doing something that scientists are actually doing. I’ve never used these kinds of instruments like cetrifuges.”

For Norbert Promagen of Waldwick, N.J., the disappointment of digging all over campus without finding a phage — a classmate spared an extra virus — has easily been overcome by the intellectual adventure of the class.

“We’ve discovered something,” said the prospective neuroscience concentrator, who is also interested in English and music. “You’re studying your own virus as opposed to someone giving you something and you are supposed to get the result that other people tell you you are supposed to get.”

Each one of these students has a whole undergraduate career ahead and, especially at Brown, the freedom to find their own way. As national educators worry about retention of students in science degree programs, these students are getting what appears to be an effective introduction to science.

“I hope to stick with it,” Cox said.