If an astronaut says, “Houston, we have a problem,” there is a good chance someone from Brown University will be fielding the distress call.

Debra Hurwitz and Mark Salvatore, graduate students in planetary geology, are taking part in NASA-sponsored field tests to prepare the agency for human exploration of destinations in space that ultimately could include Mars. Through the simulations, called Desert Research and Technology Studies (RATS), team members mimic human and robotic space exploration activities in extreme environments on Earth to investigate and develop realistic technical and mission-driven operations. This year, for the first time, the entire team of engineers, scientists, and technicians from NASA, industry, and academia will be located at Mission Control at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, coordinating with astronauts operating in the Arizona desert near Flagstaff, who are hypothetically exploring an inner solar-system asteroid.

The mock exercises, which run until Sept. 12, are important, because they bring everyone associated with a human-exploration voyage together to test all facets of what leads to a successful expedition, said James W. Head III, professor of geological sciences, who participated in NASA’s Apollo missions to the Moon in the late 1960s and early 1970s before joining the Brown faculty.

“It isn’t just mentally thinking your way there,” he said. “They’re going to be involved in the end-to-end mission.”

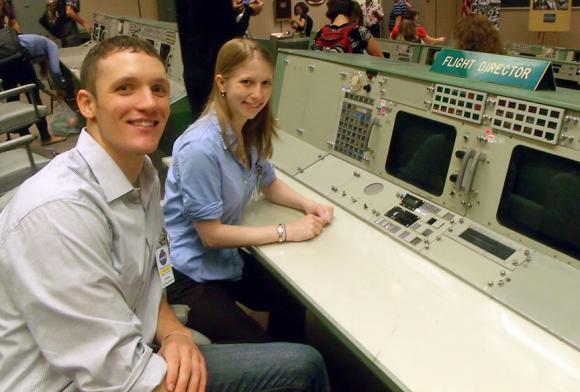

Hurwitz and Salvatore will join about two dozen others at Mission Control. They will be divided into two teams, taking day, night, and weekend shifts, and rotating responsibilities, such as communicating with the astronauts, documenting finds, analyzing images from the field and operating remote cameras.

Hurwitz, a fifth-year student from Houston, who would like to be involved in future space expeditions, said being part of Desert RATS is a “dream come true” and credited Head for helping to make it happen. “To be in Mission Control as part of a team analyzing (what astronauts find), is very exciting to me,” she said.

A major challenge confronting the bright minds at Mission Control will be to determine how best to communicate with the astronauts. There will be a gap of 50 seconds between transmissions, designed to mimic the duration of silence if astronauts were trekking around on an asteroid. By contrast, there was only a two-second lag with transmissions from the Moon for the Apollo astronauts.

“We basically have to communicate what we want them to do in 140 characters or less,” Hurwitz explained, “basically using text messages as well as verbal communication. It’s not going to be a conversation. (The astronauts) will need to be autonomous in the field.”

It all means uncharted territory for astronaut and scientist alike. “We’ll be teaching them something new while they’re teaching us something new,” said Salvatore, a fourth-year student from Cresskill, N.J., who has worked at the Johnson Space Center twice previously.

To prepare, Hurwitz and Salvatore spoke with astronaut David Scott, commander of the Apollo 15 mission who most recently visited Brown to receive an honorary degree last May, about his exploration of the Hadley-Apennine region in the near side of the Moon. The duo’s selection as Desert RATS is the “next step in Brown’s contribution to NASA’s programs and humans’ exploration of the solar system,” Head said. “It’s not only their education, but it helps their career plans as well.”