PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — New parents sometimes seem like they have a thousand questions about what will affect their babies’ health for the rest of their lives. In Providence County as part of a huge national study, 1,000 babies will help provide the answers.

That’s the total number of children that researchers at Brown University and Women & Infants Hospital plan to learn from as part of the National Children’s Study. At 105 sites around the country, a total of 100,000 children will participate from before birth until age 21, providing data on their health, lifestyles, and environmental exposures.

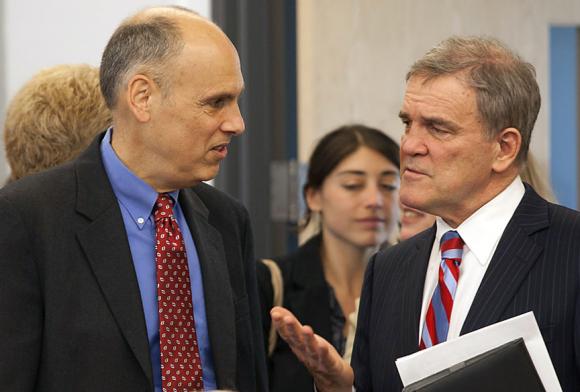

Why? Because as most of the state’s top health and government officials said Monday at the hospital during a press conference to kick off the study, the research could improve the health of every child in the country, if not the world, for decades.

Credit: Mike Cohea/Brown University

“What we need to figure out is the interplay between nature and nurture that makes us who we are,” said Dr. Alan Guttmacher, director of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, one of the National Institutes of Health. “I would argue that that’s the most important question in today’s biomedical research — to figure out the interplay between genetic and environmental factors that go into creating human health and sometimes disease.”

Guttmacher was one of many major government officials who appeared at the conference for the study, which has already recruited about 50 pregnant women and newborns living in the county’s eligible study sites. State elected leaders included Rhode Island’s U.S. Sens. Jack Reed and Sheldon Whitehouse, U.S Rep. David Ciciline, and Gov. Lincoln Chafee.

Stephen Buka, director of Brown’s Center for the Study of Human Development and principal investigator of the study in Rhode Island, said that learning all about the health of thousands of children and the environmental factors they’ve encountered will help doctors figure out ways to prevent and treat disease.

“The National Children’s study is truly ambitious in its scope and historic in its reach,” Buka said. “We together seek to identify the root causes so that we can better prevent major childhood concerns ranging from asthma, autism, diabetes, obesity, learning delays, and birth defects. We expect that the study will change the course of children’s health for generations to come.”

Guttmacher and Whitehouse compared the research to the landmark Framingham Heart Study, which tracked thousands of adults over decades to determine the causes of cardiovascular problems. Whitehouse said the NCS will be as important for children’s health as the Framingham study was for adult health.

A major Rhode Island role

Everything that the study promises to mean for the nation and the world, it also will mean for Rhode Island. But with two major sites in the study (another 1,000 children and their families will be invited to participate from Bristol County, Mass., starting next year), officials said, the study reflects especially well on the state.

The federal grants for the work in Rhode Island to date have brought more than $14 million to the state and have so far created 31 jobs, according to NCS Rhode Island officials.

“This is really a tribute to the incredible researchers we have here,” said Reed, referring to the collaboration between Brown and Women & Infants, where Dr. Maureen Phipps, interim chair of obstetrics and gynecology, is the study’s co-principal investigator. “We are not only well-positioned because of these great institutions and individuals but also because of the nature of our community. We have diversity and we have compact size.”

Dr. Edward Wing, dean of medicine and biological sciences at Brown, said the study was one of many examples of the commitments that the University is bringing to grow biomedical research in Providence and the state. Since 2002, he noted, the University and its Alpert Medical School have invested $261 million in the field, building almost 500,000 square feet of laboratory and office spaces, including at the Laboratories for Molecular Medicine at 70 Ship St. and the new Medical Education Building at 222 Richmond St., opening Aug. 15, 2011.

“We’ll have 500 new students and staff in the Jewelry District, which will contribute to the transformation of that area,” he said. “This is Brown coming off the Hill. This is Brown’s commitment to the city and the state of Rhode Island, to the people of Rhode Island.”

In addition to announcing the kick-off of the study, officials at the press conference also introduced the study’s community advisory board, made up of 20 representatives of institutions ranging from small local service organizations to major national corporations.

In a small state, the smallest people will play a big part in explaining the course of human health.

“When we collaborate on this scale we become bigger, we are bolder, and we can address questions that are extremely important,” Wing said.