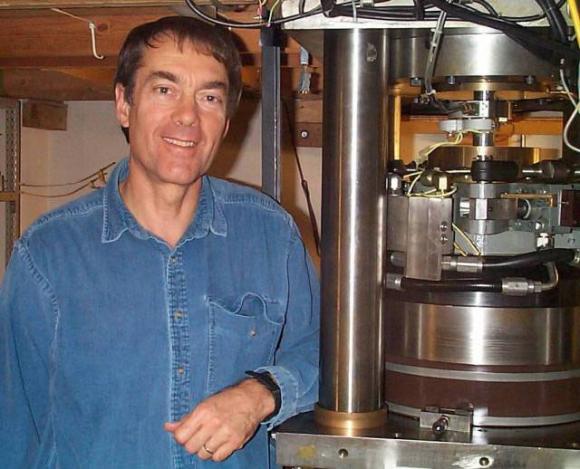

Terry Tullis, professor of geological sciences emeritus, has studied earthquakes and why they occur for more than four decades. He chairs the National Earthquake Prediction Evaluation Council, a body that advises the United States Geological Survey (USGS) both on earthquake predictability and on the validity of specific earthquake predictions. He is also a member of a select team of earthquake scientists giving general advice on earthquakes to the USGS. Richard Lewis posed a few questions about the Japanese earthquake.

What caused this earthquake?

It was caused by the rapid slip along a huge fault that separates the Pacific Plate from the Eurasia Plate as the Pacific Plate subducts, or slips under, the Eurasian Plate on which Japan sits. Such under-thrusting subduction zone events represent the largest earthquakes that have occurred in known history.

It was reported to be the fifth-largest recorded earthquake. Why was it so powerful?

Actually it is now ranked as the fourth-biggest earthquake since seismometers were invented about 1900. It was upgraded from a magnitude 8.9 to a 9.0 on the Richter scale once more processing of the seismological data was done. The size of an earthquake increases in proportion to both the size of the fault area that slips and the amount of slip. Judging from the locations of the aftershocks that tend to cover the area that slipped, fault motion occurred on a part of the plate boundary that is offshore and inclined downward toward Japan. The slipped area is about 300 miles long and about 100 miles wide. Slip occurred over this area within about a three-minute time span, and the maximum slip was about 55 feet. These numbers are very large compared to most earthquakes.

There have been scores of aftershocks since. How long will those aftershocks continue?

Aftershocks may continue for years. However, the rate of aftershocks decreases as time passes and in fact the number tends to fall off inversely with the time after the mainshock. Thus, although some may be large — and we have already seen magnitudes over 7 — there will be fewer and fewer of them and they tend gradually to get smaller.

Could the aftershocks spawn further damage to the troubled nuclear reactors?

This is of course possible, but I think this is the least of the worries about the reactors.

What tools are needed by seismologists to better predict earthquakes?

We need a better understanding of the processes that may occur leading up to earthquakes, some of which might give off detectable signals of some kind. We also need a better understanding of how earthquakes talk to each other via the stress changes that occur when an earthquake happens. We know that earthquakes can induce other earthquakes. Generally the stresses in the area of an earthquake are relaxed when it occurs, but in surrounding areas they can be increased. Sometimes this is enough to cause other earthquakes, especially if they might have been nearly ready to occur anyway because of the gradual build-up of tectonic stresses due to slow plate motion. Scientific studies are underway to evaluate whether various proposed methods of earthquake prediction actually work or not. At this stage of our knowledge, it is not so much new tools we need, but better understanding of the details of the earthquake process, especially in the preparatory stages.

What do you think of the media’s coverage of the geology and the science of earthquakes with this story?

Everything I have seen on television and heard on the radio has been quite accurate. Occasionally media people may themselves make a misstatement, but for the most part they are doing a good job of finding experts who have been well-spoken and well-informed. The main problem is that the amount of time they devote to any particular person is so short that any really in-depth explanation of the whole picture does not come out.