PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Today — Thursday — a spacecraft will enter the orbit of Mercury for the first time. A delegation from Brown University will be at mission control to witness the milestone in exploration of the mysterious planet closest to the Sun.

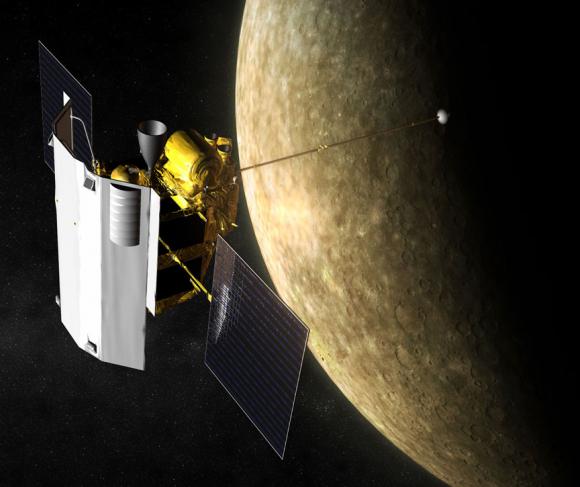

The group led by James W. Head III, professor of geological sciences, is traveling to mission headquarters outside Washington, D.C. to follow a NASA spacecraft’s insertion into Mercury’s orbit, scheduled to occur about 8:45 p.m. The mission, called MESSENGER, is the culmination of six and a half years of celestial wandering by a spacecraft that has logged 5 billion miles, circled the Sun 15 times and flown by Mercury three times in preparation for its final orbital act.

“It’s the last chapter, almost [to the mission],” said Debra Hurwitz, a fourth-year graduate student who is traveling to the John Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, site of the mission’s control center.

“This kind of seals the deal,” added David Baker, a third-year student in Head’s research group.

Mercury is one of the least known of the terrestrial planets — rocky bodies, including Earth, that comprise the innermost planetary cluster in the solar system. A NASA spacecraft, Mariner 10, flew by Mercury three times in 1974 and 1975; the planet was not visited again until MESSENGER made its first of three flybys in January 2008.

While scientists have gathered a wealth of images and useful data from the three most recent flybys, the orbital facet of the MESSENGER mission is important because it is expected to yield information on the composition and structure of Mercury’s crust, the planet’s topography and geologic history, the nature of its thin atmosphere, its active magnetosphere, the makeup of its core, and the intriguing possibility of water ice hidden in craters at the poles.

Brown has been heavily involved in Mercury research and planning for the MESSENGER mission. Head is involved in the search for polar water ice deposits using a laser altimeter; Hurwitz is seeking evidence of sinuous rilles, a topographic feature that would help bolster the case that Mercury has undergone rapid volcanic eruptions of very high volume; Laura Kerber, a fifth-year graduate student who is part of the group traveling to APL, has published papers from the earlier MESSENGER flyby data arguing that explosive volcanism has occurred on the planet, indicating that Mercury may not be as “dry” as previously thought from theoretical considerations; Baker is examining the relationship between various-sized craters found on Mercury and those found on other terrestrial planets; and second-year graduate student Jennifer Whitten, also traveling with the group, is looking at the nature of smooth plains to see if they are of volcanic origin.

Several of those in the traveling party, which includes graduate student Tim Goudge, will present posters on their Mercury research at the gathering. Research analyst Jay Dickson, research assistant Alex Tye, and group coordinator Anne Cote also are making the trip. Head, a co-investigator on the mission, will be in a control room when MESSENGER enters Mercury’s orbit. The others will be watching “the heartbeat of the spacecraft,” as Hurwitz put it, in an adjacent area.

Assuming all goes well, the group expects the first stream of data as soon as early April. “It’s going to be scientifically extremely exciting for us,” Hurwitz said.