PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — When the Brown Bears clashed with the Dartmouth Big Green on the gridiron in mid-November, researchers were keeping an entirely different kind of score than the one displayed on the board atop Dartmouth’s Memorial Field. As they have been for years now, the researchers were counting blows to the head as recorded by special sensor-equipped helmets worn by players on both teams.

What did they likely find? Based on newly published results from the 2007 season, which also included readings from the Viginia Tech Hokies, the linemen were likely knocking each other head-on play after play, while offensive specialists such as the quarterbacks and the wide receivers could never be sure where the next blow would catch them. From the perspective of the players’ long-term mental health, either situation needs close monitoring.

That’s why the researchers, led by J.J. “Trey” Crisco, professor of orthopaedics at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown, based at Rhode Island Hospital, are studying head impacts so intently. At every level of the game, from high school to the NFL, people are now paying close attention to the danger of concussion. Crisco’s team is not only providing comprehensive data, but also a new index of “head impact exposure” to better determine the exact nature of each player’s risk. It would go beyond the NCAA’s main metric of “Athlete Exposures” which merely counts the number of games and practices a player attends.

“Epidemiology of concussion injury is quite limited,” said Crisco, who in 2004 devised the algorithm that allows the Head Impact Telemetry system (Simbex, Lebanon, N.H.) to discern impact frequency, direction and severity from tiny unidirectional sensors embedded in several positions inside the helmet. “What we’ve done is add a critical outcome measure because our goal is to understand the mechanism of injury.”

Players at other positions receive most of their hits from the front and can see them coming.

Positional pounding

In the current issue of the Journal of Athletic Training, Crisco, Brown head athletic trainer Russell Fiore, and their collaborators report enough statistics about the 2007 season to make almost anyone’s head hurt. The most dramatic finding was that the most frequently battered player sustained 1,444 jolts. On average, players sustained such impacts 14.3 times per game and 6.3 times each practice.

The total number of impacts is of interest to researchers because many suspect that an accumulation of head trauma, even if no single blow results in a concussion, could still injure the brain in subtle ways.

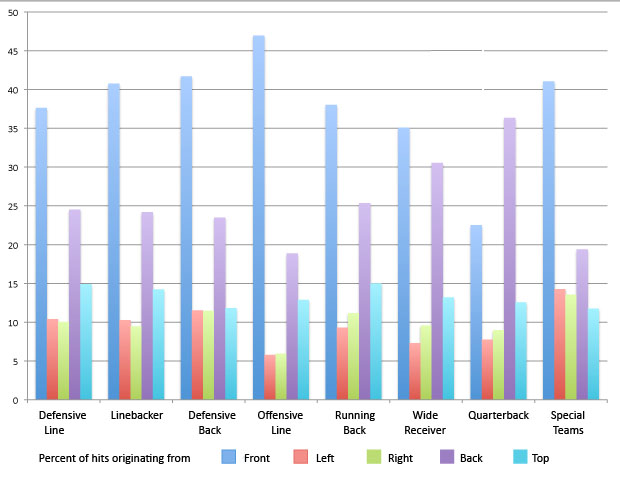

The report doesn’t just count impacts overall. It also provides a breakdown by player position. The researchers measured not only how many hits the running backs or linebackers endured, but also the location the hit on the helmet. Where a hit occurs can make a big difference in how vulnerable a player is to damage from that impact.

Offensive linemen suffer nearly three times as many blows as the quarterbacks they protect, but about half the time the impact is on the front of their helmets, suggesting that they can control where their impact will be as they jump off the line at the beginning of a play. Quarterbacks, by contrast, experience blows from behind more than from any other direction. As any football fan has observed — and as Crisco’s study quantifies — when the quarterback is hit, he is often blindsided and unprepared.

An analysis of the severity of the impacts and their correlation with concussions will follow in future papers, Crisco said.

Don’t use your head

It is already clear that repeated, significant jolts to the head are a cause for concern, Crisco said, whether the player was caught unaware or not. In fact, he says, his data suggest that players are often intentionally using their head to hit, which is a potentially dangerous idea.

“A lineman lowering his head or a running back lowering his head specifically to deliver a blow with the helmet to any part of the body, we think is something that should be addressed through coaching and rule changes,” Crisco said. “I’m a huge fan of football and of hitting in football, but intentional use of the helmet, to me is just not part of the game. I don’t think getting the head out of the game will change the game, but it will have a positive effect on reducing concussions.”