PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Most proteins are shapely, but about one-third of them lack a definitive form, at least that scientists can readily observe. These intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) perform a host of important biological functions, from muscle contraction to other neuronal actions. Yet despite their importance, “We don’t know much about them,” said Wolfgang Peti, associate professor of medicalscience and chemistry. “No one really worried about them.”

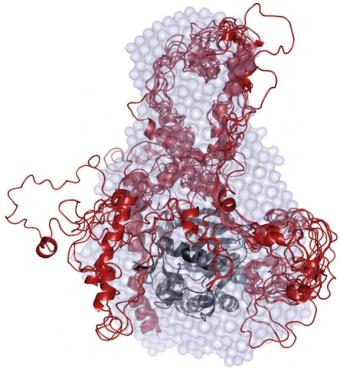

Now, Peti, joined by researchers at the University of Toronto and at Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York, has discovered the structure of three IDPs — spinophilin, I-2, and DARPP-32. Besides getting a handle on each protein’s shape, the scientists present for the first time how these IDPs exist on their own (referred to as “free form”) and what shape they assume when they latch on to protein phosphatase 1, known as “folding upon binding.” The findings are reported in the journal Structure.

Determining the IDPs’ shape is important, Peti explained, because it gives molecular biologists insight into what happens when IDPs fold and regulate proteins, such as PP1, which must ocur for biological instructions to be passed along.

“What we see is some amino acids don’t have to change much, and some have to change a lot,” Peti, a corresponding author on the paper, said. “That may be a signature how that (binding) interaction happens.”

For two years, the researchers used a variety of techniques to ascertain each IDP’s structure. With I-2, which instructs cells to divide, they used nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy to create ensemble calculations for the protein in its free and PP1-bound form. They confirmed I-2’s binding interaction with PP1 (known as the PP1:I-2 complex) with the help of small-angle X-ray scattering measurements at the National Synchrotron Light Source, located at the Brookhaven lab.

The researchers did the same thing to determine the structure of spinophilin and DARPP-32 in their free-form state and to gain insights into their shapes when they bind with PP1.

“It’s analogous to putting a sack cloth over a person,” Peti explained. “You can’t see the details, but you can get the overall shape. This is really a new way to create a structure model for highly dynamic complexes.”

Julie Forman-Kay, a senior scientist at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto and a biochemistry professor at the University of Toronto, is a co-corresponding author on the paper. Other authors include Barbara Dancheck and Michael Ragusa, Brown graduate students; Joseph Marsh, a graduate student at the University of Toronto; and Marc Allaire, a biophysicist at the Brookhaven lab.

The U.S. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the U.S. National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship program funded the research.