PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Do some people have special “susceptibility” genes that make them vulnerable to obesity and diabetes, triggered by poor diet and less exercise?

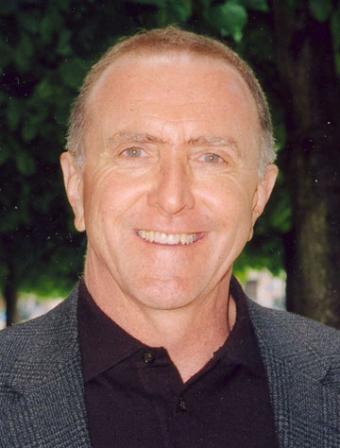

Stephen McGarvey, professor of community health and anthropology at Brown University, will attempt to answer that question as part of a new a five-year, $5.2-million National Institutes of Health grant to conduct detailed genotyping of thousands of adults in the independent nation of Samoa. The project will document genetic variation and see whether it has any association with propensities toward obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

The results should help advance the overall science of genomics-based medicine, McGarvey said.

“If we are saying that the fruits of the genomics revolution are going to be used and shared to improve clinical care, then we need to get this basic type of information from other human populations,” McGarvey said. “It’s not just European Americans or Europeans in Europe. Right now, we don’t know for a lot of other groups which drug or behavioral interventions will work best for a panoply of conditions that they are now showing as they enter the modern world. Understanding diversity in genetic susceptibility across many ethnic groups is an important scientific and ethical goal.”

Specifically, McGarvey’s effort will involve genotyping 3,000 adult Samoans in a study that will also track diet and physical activity.

Samoans are a Polynesian people in the Pacific region, a very homogeneous population that has been characterized as having very large body size and a high prevalence of obesity, diabetes and cardiac problems. The genotyping will try to determine whether there are any special “susceptibility” genes that increase the risk of obesity and diabetes and whether a genetic susceptibility could be exacerbated by unhealthy diets and insufficient exercise.

“They have a unique population history in terms of how their population was formed over the last 5,000 years,” McGarvey said. “They may have some of these genetic susceptibilities at higher or lower frequencies than other groups, and we want to understand how that diversity influences health on a worldwide basis.”

McGarvey, who is also director of the International Health Institute at Brown University, has studied the Samoan people since 1976. He said this new effort builds on earlier research that has looked at Samoans as they have become more urbanized and their physical activity and diets have changed. Those earlier efforts did find some variation on a small scale, but McGarvey said wide-scale genotyping should identify the variation definitively, if it exists.

Researchers will aim for a nuanced evaluation. They will determine whether susceptibility genes are present and whether they produce levels of obesity and diabetes only when subjects eat more but don’t exercise enough to burn excess calories.

“You want to see if the Samoans have a genetic propensity to have high instances of (diabetes or obesity) or if it is kept in check by better diet and exercise,” McGarvey said.

Researchers will incorporate a wide variety of study subjects. More than three-quarters of Samoan men are still engaged in traditional farming and fishing, for example. Researchers will try to contrast these subjects with Samoans who are living in town, working in offices, factories and shops, and may drive more and walk less.

McGarvey and his researchers will collect blood samples, study diets, measure height and weight, and take blood pressure. They will also ask about nutrition, physical activity, doctor visits, and use of medicines. Finally, researchers will evaluate demographic information such as education, employment and income, as that data can have a direct relationship to certain health behaviors.