PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Brown University biomedical engineers can now grow and assemble living microtissues into complex three-dimensional structures in a way that will advance the field of tissue engineering and may eventually reduce the need for certain kinds of animal research.

The team, led by Brown professor Jeffrey Morgan, successfully used clusters of cells grown in a 3-D Petri dish also invented by the group, in order to build microtissues of more complex shapes.

Such a finding, detailed in the March 1 issue of Biotechnology and Bioengineering and posted at the end of January on the journal’s Web site, has enormous implications for basic cell biology, drug discovery and tissue research, Morgan said.

Because the tissues Morgan’s team created in the lab are more like natural tissue, they can be constructed to have complex lace-like patterns similar to a vasculature, the arrangement of blood vessels in the body or in an organ. Morgan said that added complexity could eventually reduce the need to use animals in certain kinds of research. The National Science Foundation and the International Foundation for Ethical Research funded the study, with the latter group’s mission focused in part on reducing the use of animals in research.

“There is a need for … tissue models that more closely mimic natural tissue already inside the body in terms of function and architecture,” said Morgan, a Brown professor of medical science and engineering. “This shows we can control the size, shape and position of cells within these 3-D structures.”

But Morgan said the finding also makes an important contribution to the field of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

“We think this is one step toward using building blocks to build complex-shaped tissues that might one day be transplanted,” he said.

The new finding builds on earlier work by Morgan and a team of Brown students, which appeared in September 2007 in the journal Tissue Engineering. The earlier study highlighted the invention of a 3-D Petri dish about the size of a peanut-butter cup and made of agarose, a complex carbohydrate derived from seaweed with the consistency of Jell-O. Morgan and students in his lab developed the dish, creating a product where cells do not stick to the surface. Instead, the cells self-assemble naturally and form “microtissues.”

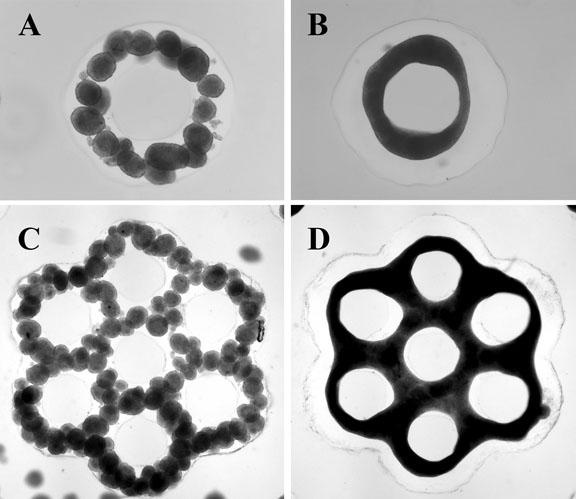

For the new research, Morgan, with students including Adam Rago and Dylan Dean, made 3-D microtissues in one 3-D Petri dish, harvested these living building blocks and then added them to more complex 3-D molds shaped either like a honeycomb, with holes, or a donut with a hole in the middle.

Those skin cells fused with liver cells in the more complex molds and formed even larger microstructures. Researchers found that the molds helped control the shape of the final microtissue.

They also found that they could control the rate of fusion of the cells by aging them for a longer or shorter time before they were harvested. The longer the wait, Morgan found, the slower the process.

Rago has since graduated from Brown, and Dean, an M.D.-Ph.D. student, has moved on from the Morgan lab to pursue his surgical rotations.