PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — A team of Brown University biomedical engineers has invented a 3-D Petri dish that can grow cells in three dimensions, a method that promises to quickly and cheaply produce more realistic cells for drug development and tissue transplantation.

The technique employs a new dish – cleverly crafted from a sugary substance long used in science laboratories – that allows cells to self-assemble naturally and form “microtissues.” A description of how the 3-D dish works appears in the journal Tissue Engineering.

“It’s a new technology with a lot of promise to improve biomedical research,” said Jeffrey Morgan, a Brown professor of medical science and engineering.

Morgan conceived and created the 3-D Petri dish with a team of Brown students led by Anthony Napolitano, a Ph.D. candidate in the biomedical engineering program. Napolitano spent two years perfecting the new dish and recently won a $15,000 award from the National Collegiate Inventors and Innovators Alliance to develop the patent-pending technology into a commercially viable product.

“This technology is an inexpensive and easy-to-use alternative to current 3-D cell culture methods,” Napolitano said. “It’s the next generation.”

The technology tackles a topic of increasing interest to scientists: creating hothouse cells that look and behave more like cells grown in the human body. Since 1877, scientists have relied on the Petri dish to grow, or culture, cells. The cells stick to the bottom of the dishes and spread out as they multiply. In the body, however, cells don’t grow that way. They are surrounded by other cells in three dimensions, forming tissues such as skin, muscle, and bone. This is what happens in Morgan’s 3-D dish.

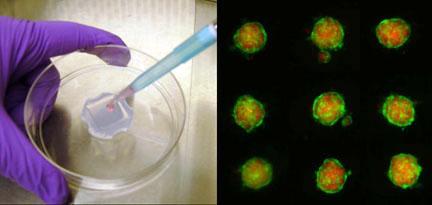

The clear, rubbery dish is the size of a silver dollar. It is made from a water-based gel made of agarose, a complex carbohydrate long used in molecular biology. This gel has a few benefits. It is porous, allowing nutrients and waste to circulate. And it is non-adhesive, so cells won’t stick to it. At the bottom of the dish sit 820 tiny recesses or wells. When cells are added to the dish –about 1 million at a time – roughly 1,000 sink to the bottom of each well and form a pile. These close quarters allow cells to self-assemble, or form natural cell-to-cell connections, a process not possible in traditional Petri dishes.

The result: microtissues consisting of hundreds of cells, even of different types. In Tissue Engineering, the Brown team describes how they combined human fibroblasts, which make connective tissue, and endothelial cells, which line the heart and blood vessels. The cells came together to form spheres and doughnut-shaped clusters. The process was quick – self-assembly took place in less than 24 hours.

“These microtissues have several potential uses,” Morgan said. “They can be used to test new cancer compounds and other drugs. And they can be transplanted into the body to regenerate tissue, such as pancreatic cells for diabetics. While there are other methods out there for making microtissues, our 3-D technology is fast, easy and inexpensive. It can make hundreds of thousands of microtissues in a single step.”

Differences in culture techniques matter in biomedicine, according to a growing body of research. Studies show sometimes dramatic differences in the shape, function and growth patterns of cells cultured in 2-D compared with cells cultured in 3-D. For example, a recent Brown study found that nerve cells grown in 3-D environments grew faster, had a more realistic shape and deployed hundreds of different genes compared to cells grown in 2-D environments.

That’s why several laboratories are pursuing 3-D cell culture methods. Brown Technology Partnerships has filed a patent application based on the technology developed in the Morgan lab and is actively pursuing licensing partners.

Napolitano was lead author of the Tissue Engineering article, and Morgan was senior author. Other members of the research team included Peter Chai, a student at The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University and Dylan Dean, an M.D./Ph.D. graduate student in the molecular pharmacology and physiology program.

The National Science Foundation funded the research.