I extend my heartfelt gratitude for the invitation to be present at this historic site on the occasion of the 60th reading of the letter of President George Washington "To the Hebrew Congregation in Newport." My gratitude derives from the fact that today's ceremony is the culmination of a period of study and reflection. The opportunity this summer to visit holy sites in Israel for the first time was a satisfying and stimulating dimension of this summer of reflection. Today's event is yet another station in a phenomenal personal journey through history's lessons. That journey began in my youth. Many of you know that the Jewish Diaspora is a prominent theme and reference point in African American Southern Baptist practice. Our songs, rituals and imagery are filled with the inspiring story of the flight from Egypt, the struggle for freedom from bondage, and the making of a community in exile. As a child, experiencing first-hand the strictures of segregation and discrimination in the South, I was enthralled and inspired by the example of wise and just Biblical elders who, through love, faith and a genuine concern for the plight of others, "made a way somehow." I feel very much that the tenets that inspired the founding of this institution reached out and made a way for me.

I am also humbled to be in the company of others who have had the privilege of speaking on this occasion. Their eminence acknowledges the importance of remembering, commemorating, and returning to the oft-linked stories of liberation and the cementing of community spirit. That the world should forget horrific events, the massive abridgement of freedom, or the toll of gross inhumanity in any sector or form, is always shocking to reasonable men and women. But, in spite of the omnipresence and perceived normalcy of these ills, citing them is an important factor in assuring our freedom as well as our humanity. Such events as this are an endorsement of the virtues and principles that long ago proved necessary in sealing and preserving that humanity. The fifteen families who founded this institution in the mid-sixteen hundreds instruct us today as they have the power to instruct every subsequent generation.

This event comes at an important moment in the history of Brown University, a moment when we at Brown are reflecting on and designing how we should acknowledge and commemorate our own history. As a university president, I take from the reading of this letter a splendid example of how our history can be more robustly brought forward to instruct students about the "common weal and woe" that we share across races, cultures, opinions and faiths. Roger Williams and Rabbi Touro, in recognizing that true freedom is impossible without the expansive care and concern for the rights of all humankind, set a powerful and enduring example for all of us today.

The fifteen Spanish and Portuguese families who journeyed to Newport in search of religious freedom formed with others of different religions a continuous chain of human beings seeking the God-granted birthright to affirm openly who they are by family line, historical ties, and religious practice. The duty to undertake that struggle has been accepted by many generations, making the search for religious freedom one of the most definingly typical of human endeavors. At the same time, this is a journey that is reconceived, redrawn and refought at every moment of history in the name of every people. Even as each group defines the motive, nature, and aims of this quest from their unique perspective, they must inevitably turn to an inviolable principle that undergirds their distinctive struggle: the right of human beings to be and acknowledge openly who they are in its fullest and truest sense. In returning always to that principle, this ancient, beautiful, and, ultimately, moving struggle is ceaselessly inspiring, forever contemporary, and always relevant.

At Brown University, we know something of the restitution of institutional history. In wrestling with how to tell a difficult story from colonial times in a truthful and yet uplifting way, we have learned that, even in the most difficult circumstances, the uncovering of older histories can recreate community, re-inspire fidelity to founding principles and embolden important new actions consistent with those ideals. Mature communities tend to forget why a sense of commonality exists in and across communities. Roger Williams' generous spirit, rooted in his belief that "weal and woe" is common to many souls, conceived of a vast and veritable community of spirit that unifies human beings across many faiths. Thus, all faiths should be free and safe to affirm and practice their beliefs. Given the extraordinary rise of inter-religious conflict in the world, this ideal is even more appropriate and compelling today.

That "all men may walk as their consciences persuade them, everyone in the name of his God" is a notion that should be imprinted upon the consciousness of every generation. In 1774 when this inspired ideal made its way into the Code of Laws, the entity that became Brown University was already 10 years old. In its youth, our University, like this institution, was struggling to raise funds to assure its future. Those responsible for that future could scarcely have anticipated that their small local College, founded out of a similar desire for freedom of religious practice, would become an exemplar in higher education, influencing the direction of public policies in the nation. Yet, in debating ideals for the College, they incorporated into its Charter the noble aims of preparing young men for "lives of usefulness and reputation." Today, we look back upon and refer to these aims with a constancy and an intentionality that would have amazed our founders.

Such principles are not to be discarded because they are awkward, inconvenient or historic. They are an all-important reference point for the ongoing conduct of affairs, the shaping of priorities and future goals, and the moral context for the institution's actions. We correctly long for consonance in our commerce with morality. A founding topology often helps us resolve or eliminate the dissonance that so easily arises when human beings noisily and erratically seek what is right and just. But, it is the living out of the these principles that poses the greatest challenge in faithfully hewing to these intentions, for founding principles can be an encumbrance to other human aspirations. The imperative to change or reinterpret those principles to address utilitarian concerns and satisfy raw self-interest is the nub of the struggle that engages nations and institutions in pursuit of their goals. Facing east, this edifice is a monument to the continuous renewal of ones moral and spiritual compass.

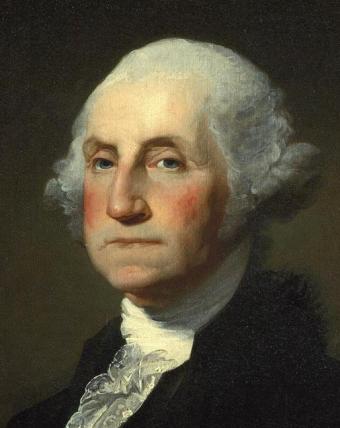

In 1790, the Warden of Congregation Jeshuat Israel wrote to George Washington in an effort to evoke the majesty of government that "gives to bigotry no quarter, to persecution, no assistance." George Washington's affirmation of this right was important, if incomplete. Just as important was the fact that observance of the teachings of this faith gave rise to generations of generous acts. Abraham Touro's bequest as well as his son Judah's bequest to Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish charities bespoke a deep commitment to the value of acknowledging that the freedoms we insist upon for ourselves are only as safe as the passion with which we seek the same freedom for others. Without this concomitant spirit, so evident in the lessons of the Torah, our freedoms are but self-serving aims. In the spirit of Judah Touro, one must commit to being "a friend to the whole human race."

We all know that these lofty and compelling ideals were largely omitted from discourse when it came to Africans and Native Americans who were held in a distinctly different light from the rest of the colonial population. George Washington's commitment to that principle on behalf of the nation eschewed the true universality that this dictum should command of adherents. In failing to apprehend the corrosive evil of slavery and the immoral inequities that it was to create for generations of descendants, Washington compromised his legacy as a moral leader. History is in the hands of those who come after for they must judge whether actions were consonant with such lofty ideals. It is, then, right and proper to reexamine these actions in different times and to apply the fullness of their historical consequences to the retelling of that history. We cannot justly be held responsible for what our forebears did but we are certainly accountable for what we fail to do. We are accountable for how we take up these ideals in our time.

This is, in essence, the mandate of the effort under way at Brown to revisit the colonial founding of our University, to understand the actions that were carried out in the name of and at the behest of the University, and to make every effort to report completely and truthfully on the actions of our founders in relation to the slave trade. It is our intention to accept the truthful account of our history, to commemorate every aspect of that history appropriately and, frankly, to place in sharper relief the paragons who point us to a positive paradigm of human behavior. There, we have much to tell: of Moses Brown and other members of the Brown family who recognized slavery's ill and took action to overturn it; of Brown students who gave orations questioning slavery; of Francis Wayland who taught Moral Science and posited for his students the problems inherent in arguments favoring the morality of slavery. Validation of these stories will not be possible if we suppress the more unseemly aspects of our history.

I am therefore immensely proud of the effort of our Committee on Slavery and Justice, the Brown family members who have helped us throughout this search for that history, and the many members of the Brown community who have assisted us in threading our way through this history in this 200th year commemorating the outlawing of slavery in Britain. The denial of religious freedom for the slaves brought to America has forever changed the landscape of religion in the African diaspora. Yet, in spite of stolen faiths, the survivors and descendants of those slaves embraced the notion of that "common weal" and courageously reseeded their faith in new religious practices incorporating treasured remnants of faiths long lost. This faith in God and the will to acknowledge a partnership with humanity became an important new asset in this community and in this nation. Similarly, the inscriptions in the Jewish Burying Ground of Newport speak of adaptations through time and continents in an effort to preserve the precious core of the Jewish faith.

Today, the stealing and sealing of faith remains a saga shaped by world events. My trip to Israel this summer came in the wake of a shocking proposal advanced by some in the Union of College and University Professors in Great Britain who proposed a debate about whether the Union should oppose cooperation with Israeli academics. This proposal is evil on several levels. The first is, of course, its inherent attempt to hold the Israeli Academy hostage to the Union's political policies, goals and interests. This attack upon the Academy is a dangerous action of a type seen many times before. Where it has succeeded, states have accelerated their tyranny over freedom of speech, societal commerce has been poisoned, and all freedoms have been compromised. Like other universities and colleges, we have affirmed our support for Israeli scholars and their academic freedom. We stand with our Israeli colleagues in fighting efforts to intimidate them into silence, conformity, or political compliance. The independence of the Academy undergirds our civic rights and stays misguided efforts at religious intolerance.

At another level, this is a form of intimidation that can and should be taken as an attack upon these individual scholars in their role as academics and in their identity with a Jewish institution. If the Union seeks to question the Israeli government's policies, the most direct route to such criticism is through British government diplomacy or, better yet, through direct commentary on Israeli government policies. We all know that the debate within Israel robustly embraces dissent. I was in Israel at the time of the summer elections and observed first-hand the degree of raucous debate about politics and Palestinian issues. That the Union chose to direct this question at the Israeli Academy is, in my view, a sign that some seek to turn opinion and arouse animus against individual Israeli students and scholars. What could be more pernicious or threatening to the freedoms we enjoy in spiritual and civic life?

Is not fear of this kind of prejudice the inspiration for the letter to George Washington seeking reassurance about his commitment to permit bigotry no quarter? Today, at the time that Britain is celebrating the 200th anniversary of the abolition of slavery, it would be sad to have to seek assurance from the leaders of Great Britain that it will censure efforts to intimidate and isolate Israeli intellectuals. The Letter of George Washington calls upon us to renew constantly our efforts to prevent bigotry and its offspring from gaining ascendency and to affirm robustly that we will again act vigorously in the name of one humanity.

Protecting the rights of the many is, happily, the implicit charge of leadership in our time. At the same time, I believe that it is incumbent on those of us who have learned first-hand about the abridgement of civic and religious rights to stand with any who is unjustly singled out for a curtailment of these rights. I am here because distinguished members of this community extended that commitment to me at a time when our country upheld the legality of withholding civil rights from African Americans. Throughout my personal journey, I have been able to count on the care and concern of Jewish men and women who were infused with the principles that they learned in their faith. I call to some of them now as I end my remarks because they have given shape to the meaning of what Judah Touro and others intended when they bequeathed their fortunes to Jews and Protestants alike.

I am the beneficiary of that generosity. I call to Aaron Lemonick, my beloved mentor, who bequeathed to me the importance of being indignant about injustice in the invisible reaches of my thoughts and actions. I call to Rabbi Eddie Feld and his wife Merle Feld who give me their friendship and show me that deep faith and upright religious identity carry an obligation to be generous in one's faith as well as in one's deeds. I call to Harold Shapiro who teaches me still by his example how to be a straight-backed leader. I owe a substantial debt to all of them and other heirs to the generous spirit of these founding families, who believed that they were tied to people like me in the "common weal and woe." That generosity in turn, inspired me to look beyond the prejudice that I suffered, and to embrace this notion of a broader community.

It is in the spirit of what they gave me that I come to reaffirm with you that the actions taken in 1770 to plant a stake here that faith is free not only infuses this ground but radiates outward to every faith and follower. Standing at the Wailing Wall in the hot June sun, I marveled at how greatly my journey from the searing sandy flats of East Texas had been buoyed by the tenets of this generous faith that reached out in so many ways to protect and guide me. Through a robust adherence to faith that embraces all, millions have moved through time, making good on the notion that we are one humanity.

Thank you for allowing me to savor these thoughts and share my gratitude with you.

Thank you for having me here today.