PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Middle school teacher Adam Newall calls it “the eternal question” of introductory algebra. As students tread water in a sea of variables, functions, and graphs, they’re bound to ask it: “When are we ever going to use any of this?”

But Newall, who teaches at Pembroke Community Middle School in Pembroke, Mass., is hearing that question a lot less often lately. He’s using a new curriculum in his seventh and eighth grade math classes that answers it right off the bat — and in a way that kids find hard to resist.

The curriculum, called Bootstrap, teaches students to program their own video games — a task that just happens to require understanding and applying fundamental concepts of algebra. Newall says the approach does wonders, engaging students in a subject from which they might otherwise shy away.

“The idea of making a video game is the allure,” he said. “But it opens [students] to the idea that they can learn math, and it’s not something that’s meant to torture people. They learn that math is something that is real and relevant and that they can use it.”

Bootstrap is a group effort of Emmanuel Schanzer, a former computer programmer turned math teacher and now a Ph.D. student in the Harvard Graduate School of Education; Kathi Fisler, professor of computer science at Worcester Polytechnic Institute; and Shriram Krishnamurthi, professor of computer science at Brown. It builds on two decades of work done at Northeastern, Brown, and other universities.

The curriculum started as a 10-week after-school program, which has been taught successfully around the country for six years. Now, based on the success of the after-school experience, Bootstrap is transitioning into an in-school program. The Bootstrap organization has set up training seminars for teachers around the country, and a few schools — like Newall’s Pembroke Community Middle School — are already using the curriculum. Two new partnerships promise to bring Bootstrap to many more schools.

Code.org, a national nonprofit that aims to expand computer science instruction in public schools, recently named Bootstrap as its official middle school math curriculum. CSNYC, a New York City-based group with similar goals, has adopted Bootstrap as well. This summer, as Code.org rolls out its national curriculum, the Bootstrap team will give additional training seminars to teachers all over the country interested in trying Bootstrap.

More than just fun and games

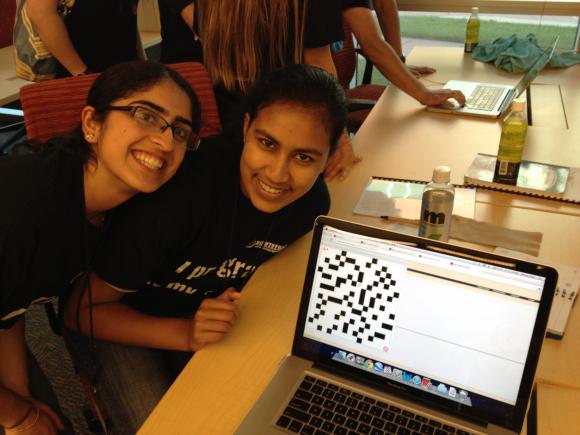

While the educators are mostly interested in the underlying math concepts, for the students, it’s the games they create that are the stars of the show.

“The whole curriculum is a sequence of steps that get you to the point where you have a working game at the end,” Krishnamurthi said. “Once we tell them they’re going to make their own game, the motivation is done. We don’t have to say any more.”

Conceptually the games are fairly simple (though surprisingly addictive). Students choose a main character, a goal for that character to reach, and a danger to avoid. Then the students learn a simple programming language to put it all in motion. And that’s where algebra comes in.

For example, in order for the program to know if a character has reached her goal or been stymied by an obstacle, the relative positions of objects must be plotted on a Cartesian grid.

“To do that, we’re going to need to know the Pythagorean theorem,” Newall said. “To understand the Pythagorean theorem we need to know square roots and squares. And [the students] will follow a lesson on how those things work in order to make it work in their game. They’re so eager to own that.”

When all is said and done, each student has a game to show off to friends and a working understanding of variables, functions, and other fundamental algebra concepts that align with Common Core math standards.

Right skills, right time

One of the reasons Krishnamurthi is so eager to get the curriculum into more middle school classes is that it catches kids at a crucial time.

“Research has found that kids change the way they talk about math right around this age,” he said. “They go from saying, ‘math is hard,’ to saying, ‘I can’t do math.’ And that’s the point where kids make the decision to drop out of algebra. When they do, they’ve actually made a career decision without even knowing it, because there’s nothing you can do in a STEM field without algebra. We’d like to get to them before they make that decision to drop out, so they at least have they can keep their options open.”

But algebra isn’t the only thing students learn through Bootstrap. They also become familiar with ins and outs of coding, a crucial skill in an increasingly digital world. When students present their games to their classmates, they’re also expected to stand up and explain the code that makes it work — an exercise software engineers call a code review.

“I do code reviews with my college students,” Krishnamurthi said. “They are one of the most challenging experiences a college student can have. It’s a hard-core professional skill. We teach it to middle schoolers as a natural part of our curricular design.”

The first time Newall taught the class, those code reviews were given at a launch party at semester’s end.

“The superintendent came; parents came. Just the amount of celebration from kids making a one-screen, side scrolling video game was more than I had ever anticipated,” Newall said.

And as for that eternal math class question, Newall says his Bootstrap students are now asking a new question.

“They go from, ‘What are we going to use this for?’ to ‘What are we going to use this for next?’”