PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Mangrove forests have been expanding northward along the Atlantic coast of Florida for the last few decades not because of a general warming trend, but likely because cold snaps there are becoming a thing of the past. That surprising finding, reported by a team of ecologists in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, provides a new and unique illustration of the speed and scale on which alterations in climate extremes have affected crucial ecosystems.

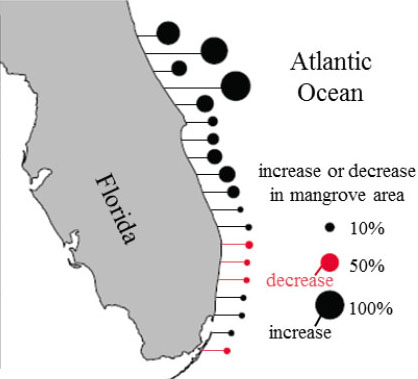

Going back 28 years, as the study based on a sophisticated analysis of satellite imagery does, a resident of Palm Coast could have encountered some mangrove forest, but the size of those forests would now be about 100 percent greater according to the researchers’ measurements of the coastal area mangroves now occupy.

“Before this work there had been some scattered anecdotal accounts and observations of mangroves appearing in areas where people had not seen them, but they were very local,” said study lead author Kyle Cavanaugh, a postdoctoral researcher at Brown University and at the Smithsonian Institution. “One unique aspect of this work is that we were able to use this incredible time series of large-scale satellite imagery to show that this expansion is a regional phenomenon. It’s a very large-scale change.”

.jpg)

James Kellner, assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and a senior co-author, added that the paper goes beyond merely documenting the northward push of mangrove forests by accounting for the most likely cause. Cavanaugh and his colleagues tested various hypotheses by correlating the satellite observations with reams of other data. What emerged from their tests of statistical significance was the area’s decline in the frequency of days where temperature dips below minus 4 C (25 F). That, not coincidentally, is a physiological temperature limit of mangrove survival.

“The most intuitive explanation is not the explanation that actually explains this pattern,” said Kellner, who is part of Brown’s Environmental Change Initiative. “The one people would most probably point to is an increase in mean temperature.”

But in the analysis, the team, which also includes researchers at the University of Maryland, had to rule out increases in mean annual or winter temperatures as well as changes in precipitation and changes in nearby urban and agricultural landcover. They also ruled out sea level rise.

Instead seemingly subtle differences from 1984 through 2011 of just 1.4 fewer days a year below 25 F in Daytona Beach or 1.2 days a year in Titusville appear to explain as much as a doubling of mangrove habitat in those areas.

Ecosystem upheaval?

In a state where mangroves enjoy environmental protections and where the plants are the namesake of streets, parks, businesses, and at least one golf course, it might appear at first blush that more mangrove habitat could be a good thing. Florida orange growers might be happy to kiss hard freezes goodbye. But Cavanagh and Kellner caution against any celebration of this apparent consequence of climate change.

“The expansion isn’t happening in a vacuum,” Cavanaugh said. “The mangroves are expanding into and invading salt marsh, which also provides an important habitat for a variety of species.”

The next question is to understand how these changes affect the lives and interactions of the species in each ecosystem.

“There’s an enormous amount of uncertainty as to what these changes mean for the food webs,” Cavanaugh said.

For now, what’s apparent is that changes well underway in Florida’s climate have seemingly led to significant changes along hundreds of miles of coastline.

In addition to Cavanaugh and Kellner, the paper’s other authors are Alexander Forde and Daniel Gruner of Maryland, and John Parker, Wilfrid Rodriguez, and Ilka Feller of the Smithsonian.

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (grant NNX11AO94G) and the National Science Foundation (grants 1065821 and 1065098) supported the research.