PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Senior biology concentrator Kathryn Yates transferred to Brown from Middlebury College in Vermont two years ago for the open curriculum and the uncommonly broad opportunity Brown offered to explore her interests. She was studying biology, but thinking about other disciplines as well.

“I’ve always been interested in trying to get over more to the engineering side,” Yates said.

There was indeed an ideal place for Yates at Brown. Her interests, coupled with a passion for sports (she’s on Brown’s squash team), fit perfectly into the orthopaedics research group led by Joseph Crisco, the Henry F. Lippitt Professor of Orthopaedics. Crisco, a former college athlete, studies the biomechanics and physics of sports, looking at questions ranging from head impacts in football, hockey, and lacrosse to the performance of baseball bats.

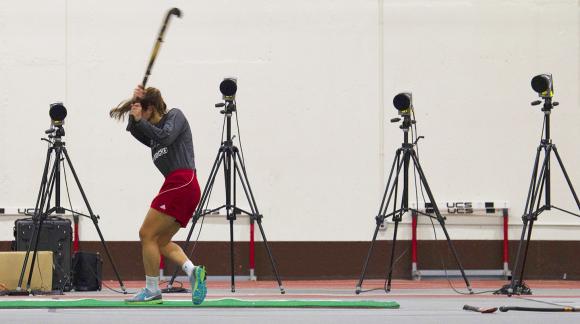

On a rainy November Sunday, Crisco, Yates, and graduate student Beth Wilcox were conducting a study of field hockey. Working with Brown’s team in a special indoor setup at the Olney-Margolies Athletic Center, they compiled measurements to discern whether different ball weights, materials and textures affect the speed of a shot.

The National Collegiate Athletics Association is funding the research. Crisco said his group’s findings may help the NCAA set standards for the kinds of balls that should or shouldn’t be used in the sport.

“It could potentially broaden the spectrum of balls allowed by the NCAA or it could tighten that up,” Crisco said.

Yates is also testing the biomechanics of a good swing. She has worked for months with her lab mates to arrange the experiments, using an array of four high-speed cameras to record whack after whack on 11 different balls. There are motion marking bits of tape on the balls, the sticks and the player’s hips.

“The main question is if the different balls have different reactions,” Yates said. “But the part that I’m studying is whether hip rotation has any impact on shot speed.”

Yates will then dive into data analysis.

“It just gives us a whole bunch of dots and we have to connect them,” she said.

The opportunity to work in Crisco’s lab gives Yates the independent study experience she needs for the biology degree she’ll earn in May. But it has also helped her realize her ambitions to explore the engineering side of biomechanics.

“I’m loving it,” she said. “It’s been great. They’ve been really great about welcoming me in to their lab. Every few days I have a moment where I’m like ‘do they know I’m not an engineer?’”

But at Brown, where independent study is a defining feature of the open curriculum, one doesn’t have to be either a biologist or an engineer. All one has to be is eager to take a whack at learning.