PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Nectar-feeding bats and busy janitors have at least two things in common: They want to wipe up as much liquid as they can as fast as they can, and they have specific equipment for the job. A study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences describes the previously undiscovered technology employed by the bat Glossophaga soricina: a tongue tip that uses blood flow to erect scores of little hair-like structures exactly at the right time to slurp up extra nectar from within a flower.

The bat’s “hemodynamic nectar mop,” as the paper dubs the tongue tip, features speed and reliability that industrial designers might envy, said lead author Cally Harper, a graduate student in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Brown University. As a matter of what nature can evolve, she said, the tongue tip is surprisingly clever.

“Typically, hydraulic structures in nature tend to be slow like the tube-feet in starfish,” Harper said. “But these bat tongues are extremely rapid because the vascular system that erects the hair-like papillae is embedded within a muscular hydrostat, which is a fancy term for muscular, constant-volume structures like tongues, elephant trunks and squid tentacles.”

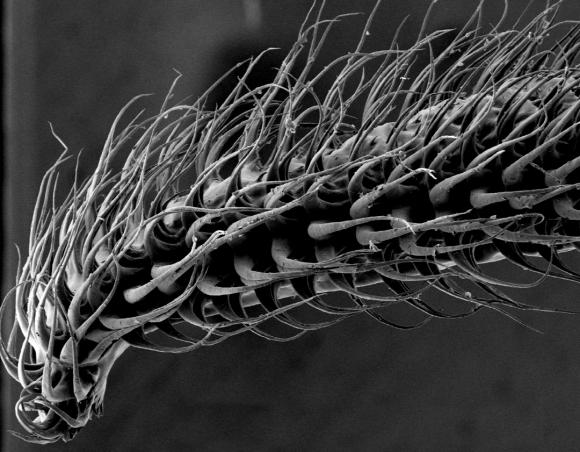

In other words, the bat’s cylindrical tongue has a mesh of muscle fibers that contract so that the tongue becomes thinner but longer (extending farther into the flower). The discovery reported in the paper is that the same muscle contraction simultaneously squeezes blood into the tiny hair-like papillae.

As blood is displaced to the tongue tip, the papillae flare out perpendicular to the axis of the tongue. In their erect state, they not only add exposed surface area, but also width, allowing the tongue to function as a highly effective nectar gathering device.

The entire extension and retraction of the tongue tip occurs within an eighth of a second. Hovering requires a lot of energy, so nectar-feeding bats must get a lot of calories quickly for it to be worthwhile.

Scientists knew about the papillae before this paper, but had always thought they were as passive as the strings on a floor mop. Recent insights by other scientists into the mechanics of hummingbird tongues prompted Harper to take a closer look at the shape of the tongue tip in bats and how it is involved in gathering nectar.

In detailed anatomical studies, Harper was able to observe clear vascular connections between the main arteries and veins of the tongue and the papillae. In experiments she could get them to erect by pumping in saline.

But the color videos of bats feeding on nectar, while challenging to create, Harper said, were especially convincing.

“That was one of my favorite parts of the study — the Aha moment,” she said. “We shot color high-speed video of the bats gathering nectar, which is challenging to obtain because color cameras require a lot of light and the one thing that bats don’t like is a lot of light.”

But along with professors and senior co-authors Beth Brainerd and Sharon Swartz, Harper figured out how to focus a lot of light right where the tongue tip would be without shining any of that light into the bats’ eyes.

What Harper could then see is that when the papillae extend, they turn from a light pink to a bright red as they fill with blood.

“That was really the icing on the cake as far as nailing this vascular hypothesis,” Harper said.

Harper said she does not know for sure whether other nectar-feeding bats also have blood-activated papillae on their similar-looking tongues. The honey possum might also employ the idea, the authors speculate in PNAS.

Other species such as hummingbirds and bees employ different rapid means of morphing their tongues for improved nectar feeding. Any or all of these highly evolved designs, the authors speculate, could give people technological inspiration.

“Together these three systems could serve as valuable models for the development of miniature surgical robots that are flexible, can change length and have dynamic surface configurations,” Harper, Brainerd and Swartz wrote.

Or maybe the discovery can just be applied to making one heck of a mop.

Funding for the study came from Sigma Xi: The Scientific Research Society, the American Microscopical Society, The Bushnell Graduate Research and Education Fund, the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (FA9550-07-1-0540) and the National Science Foundation (1052700 and 0723392).