PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — More than one in five seniors with Medicare Advantage plans received a prescription for a potentially harmful “high-risk medication” in 2009, according to an analysis by Brown University public health researchers. The questionable prescriptions were significantly more common in the Southeast United States, as well as among women and people living in relatively poor areas.

The demographic trends in the analysis, based on Medicare data from more than 6 million patients, suggest that differences in the rates of prescription of about 110 medications deemed risky for the elderly cannot be explained merely by the individual circumstances of patients, said lead author Danya Qato, a pharmacist and doctoral candidate in health services research at Brown.

“At the population level it is clear that there is a unique phenomenon occurring,” said Qato, lead author of the paper published in this month’s edition of the Journal of General Internal Medicine. “While one can reason that it might be appropriate for a particular patient to be on a particular medication, with such a preponderance of use of high-risk medications in some locations versus others, our results suggest that we cannot attribute this variation wholly to patient characteristics.”

In the analysis, Qato and co-author Dr. Amal Trivedi, assistant professor of health services, policy and practice at Brown and a hospitalist at the Providence VA Medical Center, found that 21.4 percent of the patients, or more than 1.3 million people, received at least one high-risk medication, for which there is often a safer substitute, and that 4.8 percent received at least two.

‘Geography is destiny’

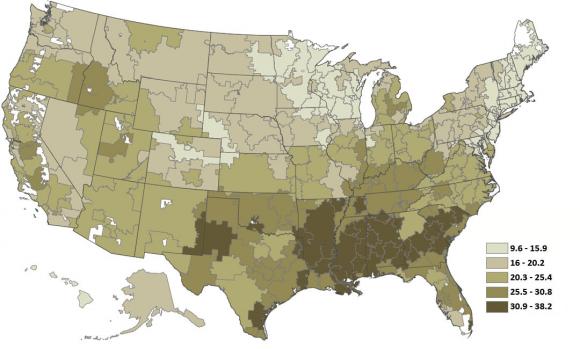

Residents of the South Atlantic, East South Central and West South Central regions of the country — an area stretching from parts of Texas to South Carolina — had a 10 to 12 percentage point higher risk of receiving potentially harmful prescriptions than people in New England, who had the lowest chance, the analysis found.

The trend persists at the finer resolution of “hospital-referral regions” or HRRs, the authors note. “The 20 lowest performing HRRs were all in the Southern region of the United States. In contrast,” they wrote in the journal, “only one of the 20 highest performing HRRs was in the South.”

Albany, Ga., had the highest rate of receipt of single high-risk prescriptions: 38.2 percent. Seniors in Alexandria, La., led the nation in receiving at least two high-risk prescriptions, with a rate of 13.5 percent. Mason City, Iowa (9.6%) and Worcester, Mass. (0.7%), had the best rate of single and multiple high-risk prescription use, respectively.

In another demographic analysis, women across the country had a 10 percentage point greater likelihood of receiving a high-risk prescription. Other differences were less stark. Generally the lower the socioeconomic status of a patient’s region, the more likely they were to receive a high-risk medication. Residents of the poorest areas had a 2.7 percentage point higher risk than the residents of the richest areas.

Complex reasons

Qato and Trivedi said the explanation for the gender difference may be straightforward. Some of the high-risk medications treat ailments specific to women or that are more common in women.

People living in poor areas, meanwhile, generally have less access to high-quality health care, Qato said, although the connection between poverty and high-risk prescriptions requires further study.

The higher risk of receiving potentially harmful prescriptions in poor areas does not explain the geographic differences, Qato said. She and Trivedi accounted for the economic statistics in their geographic analysis and for geography in their economic analysis.

Instead the reasons why people in the South are at substantially higher risk than people in the rest of the country could be a combination of many, likely interconnected, factors, Trivedi and Qato said. The factors could include higher patient demand for the drugs, a different prescribing culture, possibly higher prevalence of chronic medical problems in the region, or inadequate medical training with regard to appropriate prescribing among elderly patients.

Trivedi said officials and health care providers should take the study as a cue to improve prescribing.

“Clinicians and policymakers should work to reduce the use of these potentially inappropriate medications in older patients, because their risks outweigh their benefits and safer alternatives exist,” he said.

As a pharmacist, Qato said she hopes the research encourages seniors to take greater ownership of their health care and to be more vigilant about their prescription drug use.

“This is one of the many reminders for patients to regularly review the appropriateness and safety of their medications with their pharmacist and physician,” Qato said. “Patients are often their own best advocates.”

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant: 1T32HS019657) and the National Institute of Aging (grant: 5RC1AG036158) supported the study.