PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — A study published Feb. 6 in the Journal of the American Medical Association finds that while more seniors are dying with hospice care than a decade ago, they are increasingly doing so for very few days right after being in intensive care. The story told by the data, said the study’s lead author, is that for many seniors palliative care happens only as an afterthought.

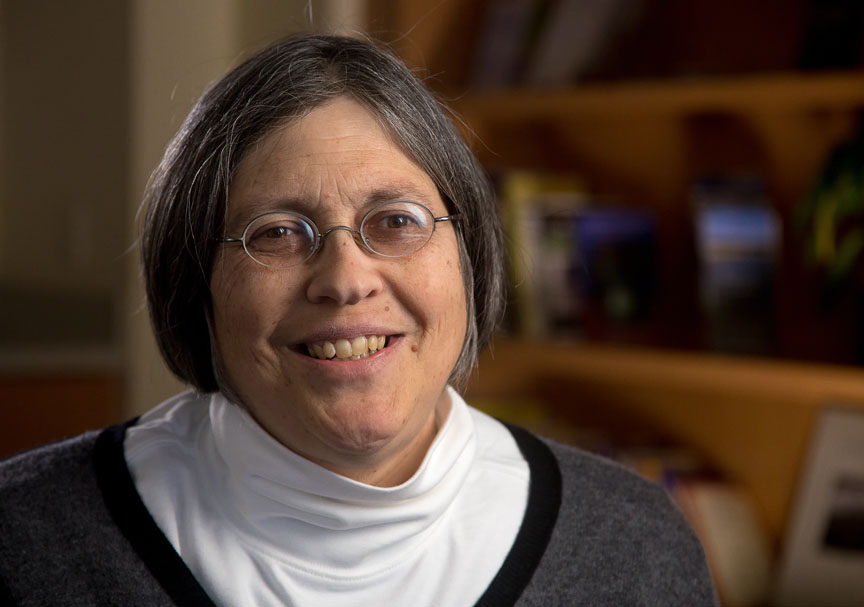

“For many patients, hospice is an ‘add-on’ to a very aggressive pattern of care during the last days of life,” said Dr. Joan Teno, professor of health services policy and practice in the Public Health Program at Brown University and a palliative care physician at Home & Hospice Care of Rhode Island. “I suspect this is not what patients want.”

The findings of Teno and her co-authors come from their analysis of the Medicare fee-for-service records of more than 840,000 people aged 66 or older who died in 2000, 2005, or 2009. They looked at where seniors died, what medical services were provided during their last 90 days of life, and how long they received them.

Over the course of the decade, hospice and hospital-based palliative care teams have made major inroads in the health care system, essentially becoming mainstream. But a deeper analysis of patients’ histories in the data, Teno said, shows that in many cases the fee-for-service system still fell short of ensuring the full measure of comfort and psychological support that hospice is meant to provide dying seniors.

Watch a brief video interview (2:17)

Data on dying

For example, while the proportion of dying seniors using hospice care increased to 42.2 percent in 2009 from 21.6 percent in 2000, the proportion who were in intensive care in the last month of life also increased to 29.2 percent in 2009 from 24.3 percent in 2000. More than a quarter of hospice use in 2009, 28.4 percent, was for three days or less, and 40 percent of those late referrals came after a hospitalization with an intensive care stay.

In 2008 the sister of study co-author Dr. David Goodman, director of the Center for Health Policy Research and a professor at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth College, had advanced cancer and died during a procedure undertaken the day before she was to enter hospice. Goodman said that aggressive care is the norm at many medical centers.

“Poor communication leading to unwanted care is epidemic in many health systems,” he said. “The patterns of care observed in this study reflect needlessly painful experiences suffered by many patients, including my sister, and other friends and family members of the research team.”

Among all patients, the percentage referred to hospice for just three days or less doubled over the decade to 9.8 percent from 4.6 percent.

“With this pattern of going from the ICU to hospice, these dying patients are getting symptom control late and can’t benefit as much from the psychosocial supports available were there a longer hospice stay,” Teno said.

Among all patients, the average amount of time with hospice in the last 30 days of life rose to 6.6 days in 2009 from 3.3 days in 2000, but intensive care days rose too: to 1.8 days in 2009 compared to 1.5 days in 2000.

Meanwhile, although seniors who died in 2009 were 11 percent more likely to die at home and 24 percent less likely to die in the hospital than those who died in 2000, the proportion who were transferred from one location to another in the last three days of life — a significant burden on patient and family — rose to 14.2 percent in 2009 from 10.3 percent in 2000. Also, the average number of transitions a patient made in the last 90 days of life increased to 3.1 in 2009 from 2.1 in 2000.

These trends reflect more ICU, more repeat hospitalizations, and more late transitions, said Vincent Mor, professor of health services policy and practice, the paper’s senior author.

Reasons and recommendations

The apparent reasons for the observed increases are a mix of regional differences in physician culture, the financial incentives of fee-for-service care, and the lack of timely communication with patients and their family about the goals of care, Teno said.

Teno and her colleagues found that people with more predictable causes of death - cancer — were much more likely to die at home and with hospice care than patients who suffered from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, a condition with a less certain end-of-life trajectory.

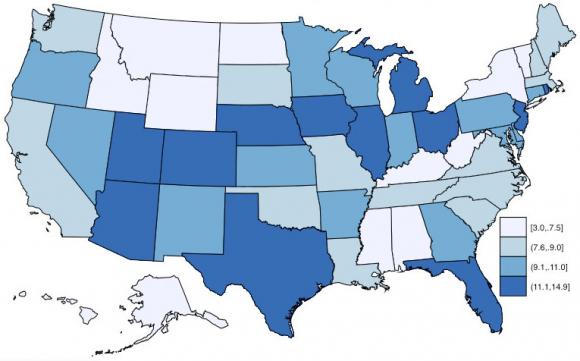

But in data not published in the paper, the researchers also observed wide state-by-state variations in late hospice referrals. In fact, her home state of Rhode Island had one of the highest rates of short stays in hospice. This variation is a product not of differences in patient health, she said, but differences in local medical culture around palliative care.

As importantly, Teno said, fee-for-service reimbursements create financial incentives for doctors and other providers to pursue aggressive measures rather than to sit down with family members and patients to develop an end-of-life care plan that incorporates their preferences.

“We need to transform our health care system, from one based on fee-for service medicine for the majority of Americans, to one where people are not paid for just one more ICU day,” Teno said. “Instead we need a system where doctors and hospitals are paid for delivering high-quality, patient-centered care that understands the dying patient’s needs and expectations and develops a care plan that honors them. We need publicly reported quality measures that hold institutions accountable to the standard of patient-centered care for the dying.”

By revealing the patterns of where, when, and for how long patients received palliative services around the time of their death, the study begins to provide such data.

In addition to Teno and Mor, other authors from are Pedro Gozalo, Susan Miller, and Thomas Scupp from Brown; Julie Bynam, Nancy Morden, and David Goodman from Dartmouth College; and Natalie Leland from the University of Southern California. Mor is also affiliated with the Providence Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

Funding for the research came from the National Institute on Aging (grant P01 AG027296) and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.