PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — First they took over chess. Then Jeopardy. Soon, computers could make the ideal partner in a game of Draw Something (or its forebear, Pictionary).

Researchers from Brown University and the Technical University of Berlin have developed a computer program that can recognize sketches as they’re drawn in real time. It’s the first computer application that enables “semantic understanding” of abstract sketches, the researchers say. The advance could clear the way for vastly improved sketch-based interface and search applications.

The research behind the program was presented last month at SIGGRAPH, the world’s premier computer graphics conference. The paper is now available online, together with a video, a library of sample sketches, and other materials.

Computers are already pretty good at matching sketches to objects as long as the sketches are accurate representations. For example, applications have been developed that can match police sketches to actual faces in mug shots. But iconic or abstract sketches — the kind that most people are able to easily produce — are another matter entirely.

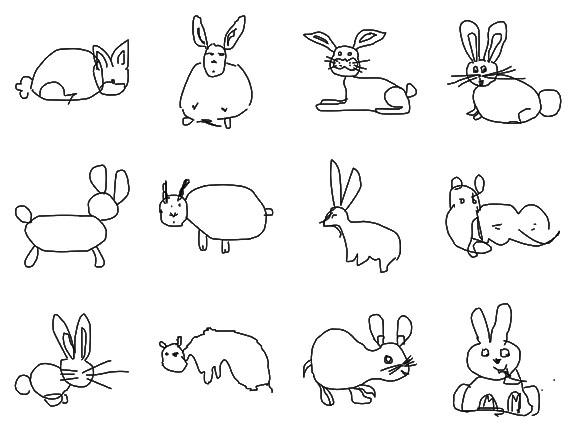

For example, if you were asked to sketch a rabbit, you might draw a cartoony-looking thing with big ears, buckteeth, and a cotton tail. Another person probably wouldn’t have much trouble recognizing your funny bunny as a rabbit — despite the fact that it doesn’t look all that much like a real rabbit.

“It might be that we only recognize it as a rabbit because we all grew up that way,” said James Hays, assistant professor of computer science at Brown, who developed the new program with Mathias Eitz and Marc Alexa from the Technical University in Berlin. “Whoever got the ball rolling on caricaturing rabbits like that, that’s just how we all draw them now.”

Getting a computer to understand what we’ve come to understand through years of cartoons and coloring books is a monumentally difficult task. The key to making this new program work, Hays says, is a large database of sketches that could be used to teach a computer how humans sketch objects. “This is really the first time anybody has examined a large database of actual sketches,” Hays said.

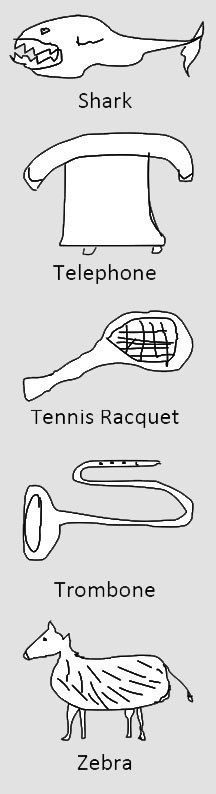

To put the database together, the researchers first came up with a list of everyday objects that people might be inclined to sketch. “We looked at an existing computer vision dataset called LabelMe, which has a lot of annotated photographs,” Hays said. “We looked at the label frequency and we got the most popular objects in photographs. Then we added other things of interest that we thought might occur in sketches, like rainbows for example.”

They ended up with a set of 250 object categories. Then the researchers used Mechanical Turk, a crowdsourcing marketplace run by Amazon, to hire people to sketch objects from each category — 20,000 sketches in all. Those data were then fed into existing recognition and machine learning algorithms to teach the program which sketches belong to which categories. From there, the team developed an interface where users input new sketches, and the computer tries to identify them in real time, as quickly as the user draws them.

As it is now, the program successfully identifies sketches with around 56-percent accuracy, as long as the object is included in one of the 250 categories. That’s not bad, considering that when the researchers asked actual humans to identify sketches in the database, they managed about 73-percent accuracy. “The gap between human and computational performance is not so big, not as big certainly as it is in other computer vision problems,” Hays said.

The program isn’t ready to rule Pictionary just yet, mainly because of its limited 250-category vocabulary. But expanding it to include more categories is a possibility, Hays says. One way to do that might be to turn the program into a game and collect the data that players input. The team has already made a free iPhone/iPad app that could be gamified.

“The game could ask you to sketch something and if another person is able to successfully recognize it, then we can say that must have been a decent enough sketch,” he said. “You could collect all sorts of training data that way.”

And that kind of crowdsourced data has been key to the project so far.

“It was the data gathering that had been holding this back, not the digital representation or the machine learning; those have been around for a decade,” Hays said. “There’s just no way to learn to recognize say, sketches of lions, based on just a clever algorithm. The algorithm really needs to see close to 100 instances of how people draw lions, and then it becomes possible to tell lions from potted plants.”

Ultimately a program like this one could end up being much more than just fun and games. It could be used to develop better sketch-based interface and search applications. Despite the ubiquity of touch screens, sketch-based search still isn’t widely used, but that’s probably because it simply hasn’t worked very well, Hays says.

A better sketch-based interface might improve computer accessibility. “Directly searching for some visual shape is probably easier in some domains,” Hays said. “It avoids all language issues; that’s certainly one thing.”