PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Species’ ability to overcome adversity goes beyond Darwin’s survival of the fittest. Climate change has made sure of that. In a new study based on simulations examining species and their projected range, researchers at Brown University argue that whether an animal can make it to a final, climate-friendly destination isn't a simple matter of being able to travel a long way. It’s the extent to which the creatures can withstand rapid fluctuations in climate along the way that will determine whether they complete the journey.

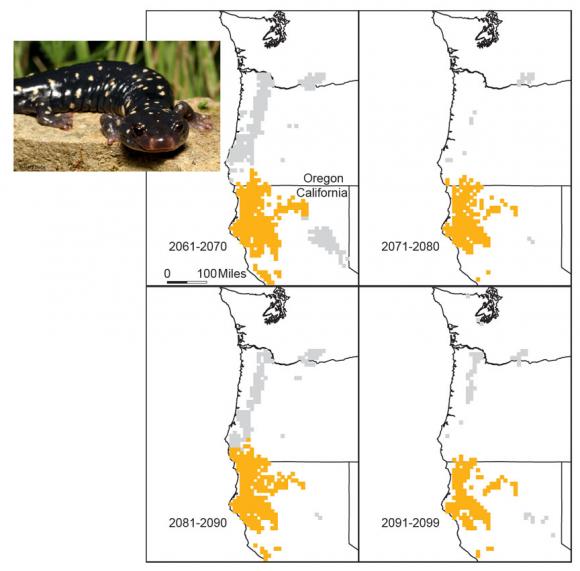

In a paper in Ecology Letters, Regan Early and Dov Sax examined the projected “climate paths” of 15 amphibians in the western United States to the year 2100. Using well-known climate forecasting models to extrapolate decades-long changes for specific locations, the researchers determined that more than half of the species would become extinct or endangered. The reason, they find, is that the climate undergoes swings in temperature that can trap species at different points in their travels. It’s the severity or duration of those climate swings, coupled with the given creature’s persistence, that determines their fate.

“Our work shows that it’s not just how fast you disperse, but also your ability to tolerate unfavorable climate for decadal periods that will limit the ability of many species to shift their ranges,” said Sax, assistant professor of biology in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. “As a consequence, many species that aren’t currently of conservation concern are likely to become endangered by the end of the century.”

The researchers chose to study frogs, salamanders, and toads because their living areas are known and their susceptibility to temperature changes has been well studied. Based on that information, they modeled the migratory paths for each creature, estimating their travels to be about 15 miles per decade. The climate models showed fluctuations in temperatures in different decades severe enough that four creatures would become extinct, while four other species would become endangered at the least. The other seven would “fare OK,” Early said, “but they all lose out a lot.”

The temperature swings can cause a species to be stopped in its tracks, which means that it has to do double time when the climate becomes more favorable. “Instead of getting warmer, it can get cooler,” said Early, the paper’s lead author, of the climate forecasts. “That means that species can take two steps forward, but may be forced to take one step backward, because the climate may become unsuitable for them. Unfortunately, if they take a step back, they have to make up all of that ground. That’s what causes the gaps in the climate path.”

The study is unique also in that it considers at species’ ability to weather adverse intervals. Early and Sax said unfavorable climate lasting a decade would put the species in a bind. If the interval lasted two decades or more, it was likely the species would become extinct. “We’ve identified one critical piece of information that no one’s really thought about, and that is what’s the ability of species to persist under non-optimal conditions,” Sax said. "If you move to those conditions, can it hang on for a while? The answer will vary for different species.”

Rapid changes to climate already being witnessed underscores the study’s value. A growing number of scientists believe climate change is intensifying so quickly that the planet is hurtling toward a sixth mass extinction in history — and the first widespread perishing of creatures since the dinosaurs’ reign ended some 65 million years ago. For the first time, species are grappling not just with projected temperatures not seen for the last 2 million years but also with a human-shaped landscape that has compromised and fragmented animals’ natural habitats.

Confronted with these realities, Early and Sax say wildlife managers may need to entertain the idea of relocating species, an approach that is being hotly debated in conservation circles. “This study suggests that there are a lot of species that won’t be able to take care of themselves,” Sax said. “Ultimately, this work suggests that habitat corridors will be ineffective for many species and that we may instead need to consider using managed relocation more frequently than has been previously considered.”

Brown University, the U.S. Forest Service and the Portuguese Foundation of Science and Technology funded the research.