PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Increasingly, the Earth’s climate appears to be more connected than anyone would have imagined. El Nino, the weather pattern that originates in a patch of the equatorial Pacific, can spawn heat waves and droughts as far away as Africa.

Now, a research team led by Brown University has established that the climate in the tropics over at least the last 2.7 million years changed in lockstep with the cyclical spread and retreat of ice sheets thousands of miles away in the Northern Hemisphere. The findings appear to cement the link between the recent Ice Ages and temperature changes in tropical oceans. Based on that new link, the scientists conclude that carbon dioxide has played the lead role in dictating global climate patterns, beginning with the Ice Ages and continuing today.

“We think we have the simplest explanation for the link between the Ice Ages and the tropics over that time and the apparent role of carbon dioxide in the intensification of Ice Ages and corresponding changes in the tropics,” said Timothy Herbert, professor of geological sciences at Brown and the lead author of the paper in Science.

“It certainly supports the idea of global sensitivity of climate to carbon dioxide as the first order of control on global temperature patterns,” Herbert added, “but we don’t know why. The answer lies in the ocean, we’re pretty sure.”

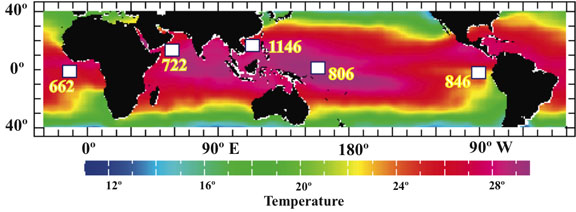

The research team, including scientists from Luther College in Iowa, Lafayette College in Pennsylvania, and the University of Hong Kong, analyzed cores taken from the seabed at four locations in the tropical oceans: the Arabian Sea, the South China Sea, the eastern Pacific and the equatorial Atlantic Ocean.

They decided to zero in on tropical ocean surface temperatures because these vast bodies, which make up roughly half of the world’s oceans, in large measure orchestrate the amount of water in the atmosphere and thus rainfall patterns worldwide, as well as the concentration of water vapor, the most prevalent greenhouse gas.

Looking at the chemical remains of tiny marine organisms that lived in the sunlit zone of the ocean, the scientists were able to extract the surface temperature for the oceans for the last 3.5 million years, well before the beginning of the Ice Ages. Beginning about 2.7 million years ago, the geologists found that tropical ocean surface temperatures dropped by 1 to 3 degrees Celsius (1.8 to 5.4 degrees Fahrenheit) during each Ice Age, when ice sheets spread in the Northern Hemisphere and significantly cooled oceans in the northern latitudes. Even more compelling, the tropics also changed when Ice Age cycles switched from roughly 41,000-year to 100,000-year intervals.

“The tropics are reproducing this pattern both in the cooling that accompanies the glaciation in the Northern Hemisphere and the timing of those changes,” Herbert said. “The biggest surprise to us was how similar the patterns looked all across the tropics since about 2.7 million years ago. We didn’t expect such similarity.”

Climate scientists have a record of carbon dioxide levels for the last 800,000 years — spanning the last seven Ice Ages — from ice cores taken in Antarctica. They have deduced that carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere fell by about 30 percent during each cycle, and that most of that carbon dioxide was absorbed by high-latitude oceans such as the North Atlantic and the Southern Ocean. According to the new findings, this pattern began 2.7 million years ago, and the amount of atmospheric carbon dioxide absorbed by the oceans has intensified with each successive Ice Age. Geologists know the Ice Ages have gotten progressively colder — leading to larger ice sheets — because they have found debris on the seabed of the North Atlantic and North Pacific left by icebergs that broke from the land-bound sheets.

“It seems likely that changes in carbon dioxide were the most important reason why tropical temperatures changed, along with the water vapor feedback,” Herbert said.

Herbert acknowledges that the team’s findings leave important questions. One is why carbon dioxide began to play a major role when the Ice Ages began 2.7 million years ago. Also left unanswered is why carbon dioxide appears to have magnified the intensity of successive Ice Ages from the beginning of the cycles to the present. The researchers do not understand why the timing of the Ice Age cycles shifted from roughly 41,000-year to 100,000-year intervals.

Contributing authors are Laura Cleaveland Peterson at Luther College, Kira Lawrence at Lafayette College and Zhonghui Liu at the University of Hong Kong. The U.S. National Science Foundation and the Evolving Earth Foundation funded the research. The cores came from the Ocean Drilling Program, sponsored by the NSF, and the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program.