PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — The moon may harbor water ice in frigid pockets at its poles. Scientists now hope to find out for sure by slamming a rocket into a crater and examining the debris that’s kicked up.

The NASA mission, called LCROSS for Lunar CRater Observing and Sensing Satellite, takes place this Friday. An upper-stage rocket is scheduled to crash into the Cabeus crater near the moon's south pole (see image below) at approximately 7:30 a.m. EDT; a second spacecraft with the instruments will follow to analyze the ejected debris and will crash into the same area minutes later.

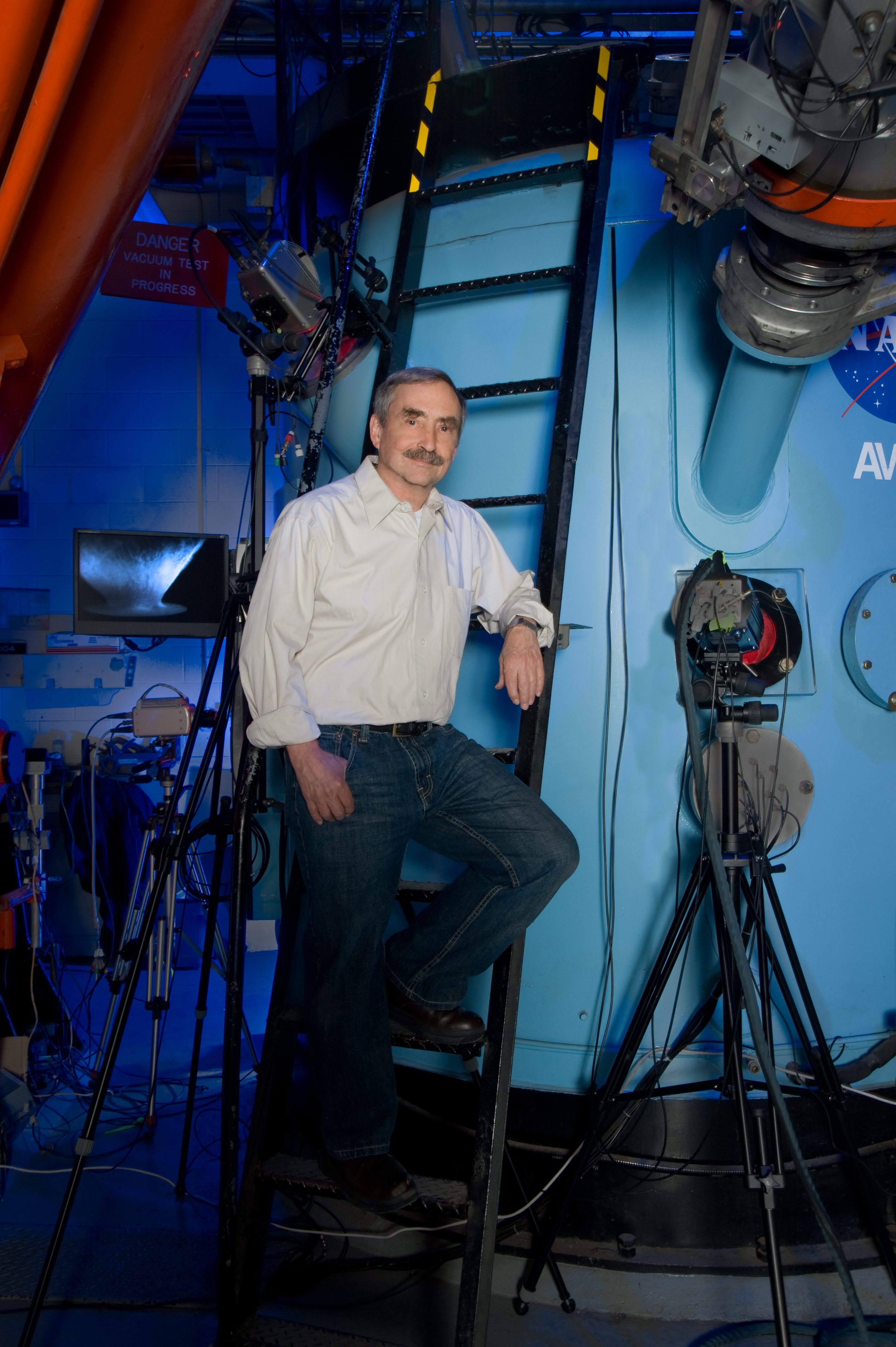

Peter Schultz, professor of geological sciences at Brown, is a co-investigator of LCROSS who helped to design the mission, which involves instruments that will swoop in and search for signs of water in the ejected debris. He will be at mission control at the NASA Ames Research Center in California for the event.

“We’re hunting for how water ice was stored and trapped in these permanently shadowed areas over billions of years,” Schultz said, “and we want to find out how much there is.”

LCROSS was launched with the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) aboard an Atlas V rocket in June and then parted ways. While LRO currently is cruising in a polar orbit about 31 miles above the lunar surface, LCROSS kept going, still attached to the upper-stage of the rocket that launched them into space. Space watchers on the East Coast with telescopes should be able to witness the separation about nine and a half hours before the impact.

Cabeus crater, site of the LCROSS impact, is located on the moon’s south pole. The region is of great interest to explorers because permanently shadowed regions are bitterly cold and may hold buried deposits of water ice delivered by cometary impacts, interactions with the solar wind or degassing from the moon’s interior. The deposits may have accumulated in these “cold-trap” regions over billions of years. If enough of these resources exist to make mining practical, future long-term human missions to the moon could save the considerable expense of hauling water from Earth, according to NASA.

“This could be the place that we could go to mine water for a permanent lunar base,” Schultz said. “It tells us something about how water was delivered to the moon and other planets in a sort of cosmic rain,” meaning impacts from comets over eons.

What makes LCROSS unique, said Brendan Hermalyn, a graduate student working with Schultz who also will be watching the impact at NASA Ames, is that it’s planned.

“We’re going to be watching this, this bird’s eye view of what’s occurring,” he said. “This is a dream, because normally you see it (an impact) when it’s on the surface, after the fact.”

Schultz and his students have been preparing for the last four years by doing detailed experiments and modeling to understand how high above the surface debris will be thrown, to interpret the impact flash, and to develop strategies to interpret the collision afterwards. The experiments have been done at the NASA Ames Vertical Gun Range, at the NASA Ames Research Center.

In 2005, the Deep Impact mission collided with a comet in order to see what was below the surface. Schultz, a co-investigator on that NASA mission, said that “this won’t be nearly as spectacular but the results will be equally important.”