PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — A Brown University archaeologist and team of engineers have been awarded $2.6 million from the National Science Foundation to use computer vision and pattern recognition in an archaeological excavation. The team is setting out to change the way archaeologists conduct fieldwork by developing innovative techniques for excavation, reconstruction, and interpretation during the next four years.

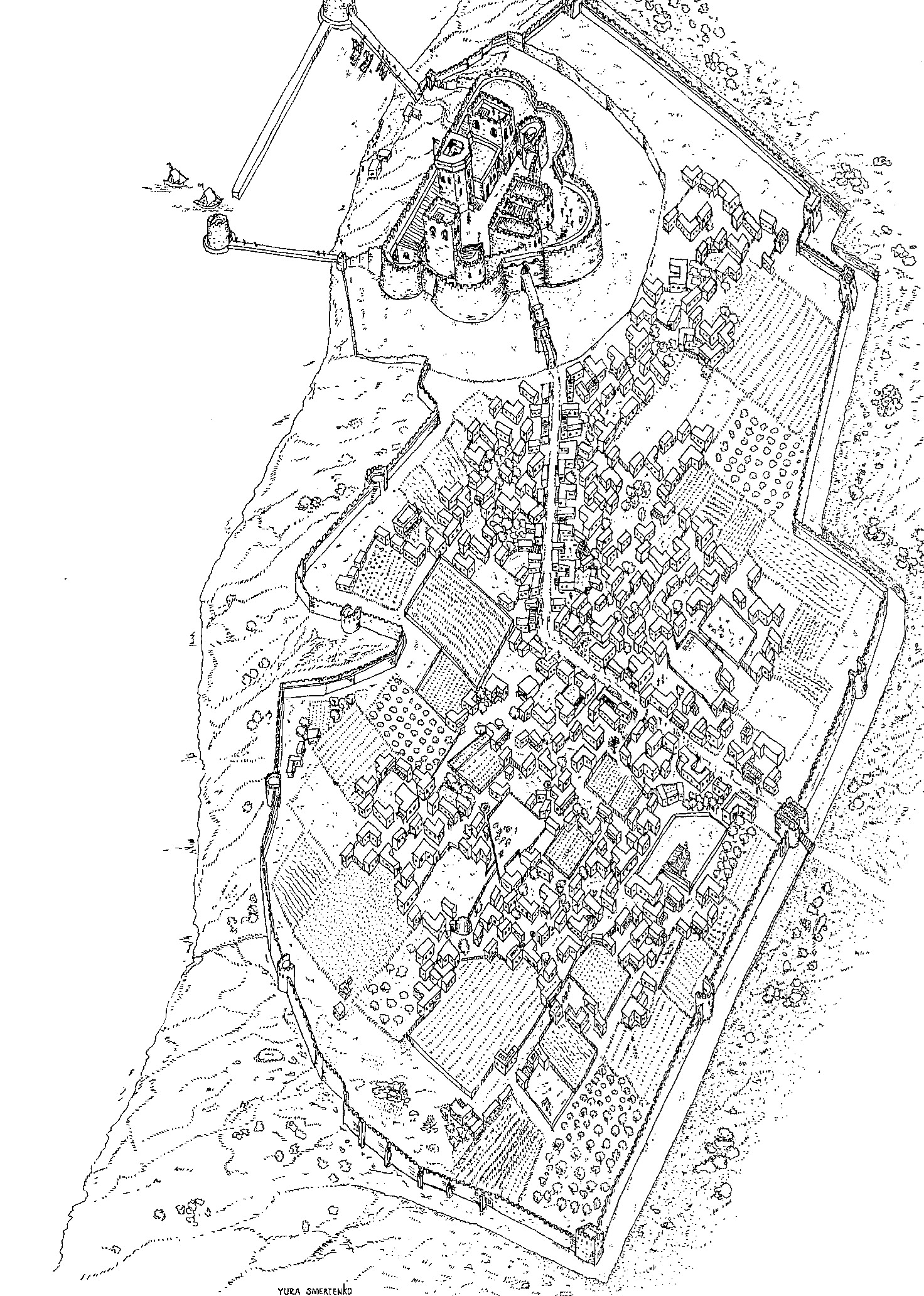

The work will focus on the site of Apollonia-Arsuf, located on the Mediterranean coast in Israel. The site has been under archaeological excavation and conservation since the 1950s and was formally recognized in 2004 as one of the 100 most endangered world monuments by the World Monuments Fund.

The team’s main goal is to develop a visual archaeological database (VAD), which will transform the current slow and tedious documentation process of an excavation. Video cameras and digital scanning stations will be installed around the site to maintain a continuous visual recording of excavation activity. Excavators will also be able to immediately process artifacts by inputting text, video, still images, dense-data 3-D laser scans, and spatial position coordinate information into the database. The VAD will allow for immediate and efficient access, search, and image and 3-D scene reconstruction of the collected data.

Archaeologist Katharina Galor, one of the principal investigators, says her field’s current protocol — relying on written field notes — is an outdated system. “We use written words to describe our findings when we should be using images and video to make the documentation process more efficient, accurate, and accessible to others,” she said. “The more precisely we can physically reproduce what is left, and the more accurately we can piece together broken and dispersed pieces, the greater our chances of reconstructing and understanding the past truthfully.”

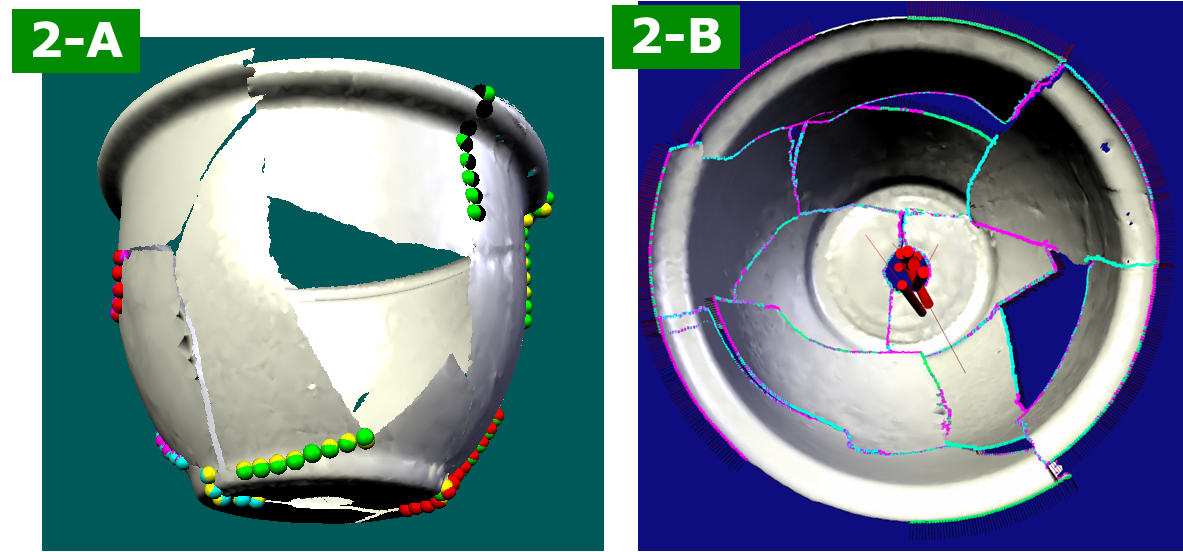

The other significant goals of this project involve using computer vision and pattern recognition to reconstruct the Crusader Castle and archaeological artifacts from Hellenistic through medieval period remains. The castle, which collapsed in the 13th century and is more than 80 percent ruined, is located on the shore of the modern town of Herzliya. Enormous architectural fragments have fallen to the beach below, into the moat, and under ocean water, making it difficult to obtain precise measurements and other information from the pieces. Using 3-D laser scanners, multiple still and/or video images, and geometry-based methods, the scientists will be able to analyze the architectural fragments, then view and manipulate the elements, and virtually rebuild the castle. The geometry-based methods will also be used to reconstruct pottery, glass vessels, statues, or other decorative blocks from the site. The team plans to develop an interactive archaeology visualization environment which will enable users to use a “walkthrough mode” to explore virtual excavation trenches and the excavation process.

The team states, “These tools will allow unprecedented access to and analysis of past human activity, with geometry providing the capability to recognize, visualize, and evaluate forms of material culture accurately, rapidly and (above all), non-destructively.” Reaching beyond archaeology, the developments in algorithms and software will be applicable to homeland security, medical imaging, remote collaboration, education, entertainment, and in the areas of geometric learning, 2-D and 3-D shape theory, and database design.

The research team includes David Cooper, professor of engineering; Katharina Galor, adjunct assistant professor in the program in Judaic studies; Benjamin Kimia, professor of engineering; and Gabriel Taubin, associate professor of engineering, along with colleagues from the Institute of Archaeology at Tel Aviv University, University of North Carolina, and the Institute for Visualization of History. The group will also collaborate with the digital humanities group of the Cogut Center for the Humanities at Brown.

On the partnership between archaeology and engineering, Cooper said, “We come from completely different worlds and speak different languages, but we have the same goal: to extract information and gather validated information that is easy to use.”

For more information about the excavation site, visit www.brown.edu/apollonia.