PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Two great obstacles to hydrogen-powered vehicles lie with fuel cells. Fuel cells, which like batteries produce electrical power through chemical reactions, have been plagued by their relatively low efficiency and high production costs. Scientists have tested a wide assortment of metals and materials to overcome the twin challenge.

Now a team led by Brown University chemistry Professor Shouheng Sun has mastered a Rubik’s Cube-like dilemma for dealing with platinum, a precious metal coveted for its ability to boost a chemical reaction in fuel cells. They show that shaping platinum into a cube greatly enhances its efficiency in a phase of the fuel cell’s operation known as oxygen reduction reaction. Sun’s results have been published online in the journal Angewandte Chemie. The paper was selected as a Very Important Paper, reserved for less than five percent of manuscripts submitted to the peer-reviewed journal.

Platinum helps reduce the energy barrier – the amount of energy needed to start a reaction – in the oxidation phase of a fuel cell. It is also seen as beneficial on the other end of the fuel cell, known as the cathode. There, platinum has been shown to assist in oxygen reduction, a process in which electrons peeled from hydrogen atoms join with oxygen atoms to create electrical energy. The reaction also is important because it only produces water. This byproduct – rather than the global warming gas carbon dioxide – is a big reason why hydrogen fuel cells are a tantalizing area of research from carmakers in Detroit to policymakers in Washington.

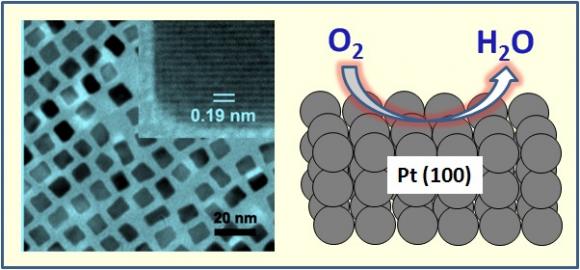

But scientists have had trouble maximizing platinum’s potential in the oxygen reduction reaction. The barriers chiefly revolve around shape and surface area – geometry and geography, so to speak. What Sun has learned is that molding platinum into a cube on the nanoscale enhances its catalysis – that is, it boosts the rate of a chemical reaction.

“For the first time, we can control the morphology of the particle to make it more like a cube,” Sun said. “People have had very limited control over this process before. Now we have shown it can be done uniformly and consistently.”

During his experiments, Sun, along with Brown graduate engineering student Chao Wang and engineers from the Japanese firm Hitachi Maxwell Ltd., created polyhedron and cube shapes of different sizes by adding platinum acetylacetonate (Pt(acac)2) and a trace amount of iron pentacarbonyl (Fe(CO)5) at specific temperature ranges. The team found that cubes were more efficient catalysts, owing largely to their surface structure and their resistance to being absorbed by the sulfate in the fuel cell solution.

“For this reaction, the shape is more important than the size,” Sun said.

The next step, Sun added, is to build a polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell and test the platinum nanocubes as catalysts in it. The team expects the experiments will yield fuel cells with a higher electrical output than previous versions.

“It’s like science fiction, but we’re a step closer now to the reality of developing a very efficient platinum catalyst for hydrogen cars that produce only water as exhaust,” Sun said.

Hitachi Maxell chemical engineers Hideo Daimon, Taigo Ondera and Tetsunori Koda, a visiting engineer at Brown, contributed to the research.

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation and by the Office of the Vice President of Research at Brown University through its Research Seed Fund.