Civil War enthusiasts have been following the online “Disunion” series in the New York Times with avid interest. How did that series come to be and how did you become a contributor?

Last summer, some friends of mine who work for the Times invited me to discuss the feasibility of launching an online series of articles about the coming of the Civil War. We had a few ideas — that it would be good to concentrate on a single day, 150 years ago, and report on it as if it was happening all over again. That it would be interesting to use the flexibility of the Internet to get at some new ways of writing history — with links, interactivity, and a chance for readers to write in. And that we wanted to support fresh, new writing on the Civil War, which is not exactly a new history topic. The results have been amazing, I think better than any of us dared to hope for.

Can you put your finger on why the events leading up to the Civil War, the war itself, and Lincoln as its central character create the such a compelling story?

It’s still the defining event in American history. It’s by far the bloodiest conflict we ever lived through, and it pulled the United States definitively into the modern era. It’s one of the most extraordinary civil wars ever experienced by any country for its length and the intensity of the fighting. And at the center of it all, a man so complex, from so simple a background, with such a powerful capacity for language — he’s utterly beguiling. And Brown is one of the great places to study him. He never gets boring.

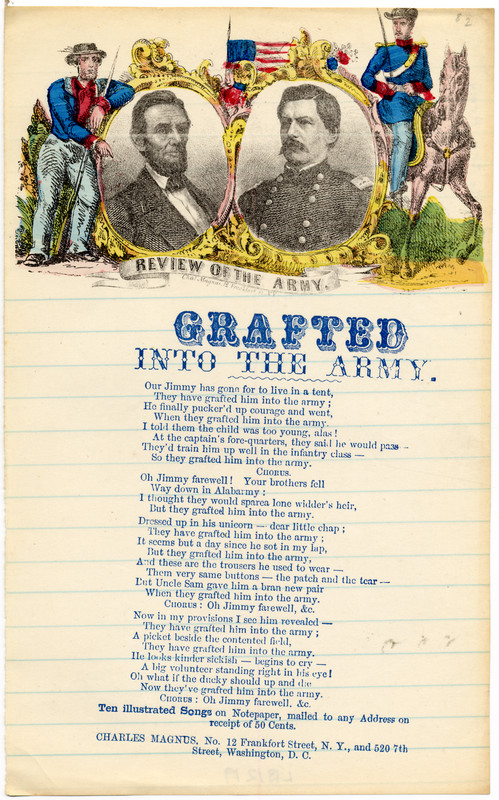

Credit: The John Hay Library/Brown University

Brown’s Hay Library is a repository of Lincoln and Civil War history. Is that a part of your inspiration and research?

Absolutely. The Hay has extraordinary things in Lincoln’s hand and images of him and life masks all on display in a special room. And of course it has items relating to John Hay, Lincoln’s secretary, from the Brown class of 1858. But just as important, it has a world-class reference collection relating to Lincoln. It is mighty difficult to find a book about Lincoln that is not in the Hay.

Historical research, in the form of digging through original documents and sources is often daunting and time consuming. Can you talk about how the availability of digitized source material has changed the process for historians?

It has made the research easier — vastly so, because certain visionary libraries like the Library of Congress have put everything online. But it has also made it more overwhelming, because so much is available that it increases the responsibility to sift it and to make sure it’s accurate. There’s a lot of possibility for inaccuracy when dealing with such a glut. And we do not want to be dishonest writing about Lincoln. Still, the positives outweigh the negatives by a wide margin. Like every other form of information, history is speeding up.

Blogs like “Disunion” appear to be a new way of making history accessible to those who might not sit down and read a tome on the Civil War or a Lincoln biography — and the series already has a healthy following on Facebook. Is that part of your goal?

Absolutely. The goal was to reach readers who want to be well informed and relearn this essential history, but not to become specialists. No particular reader was defined; we just felt that if we put great stories up every day, people would read them. And the result has been fantastic. A lot of readers, from all demographics, are checking in every day."

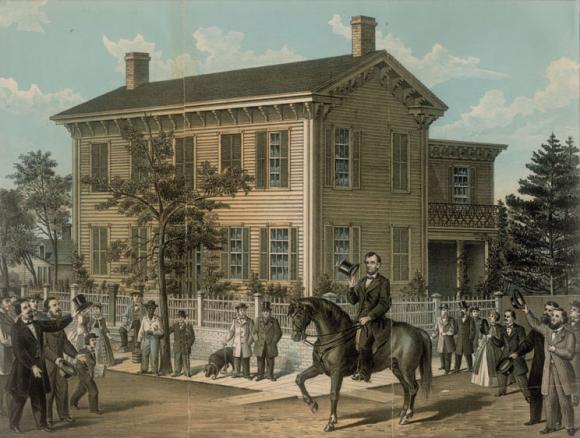

Right now, you are authoring the blog’s close examination of Lincoln’s 1861 journey from Springfield, Ill., to Washington, D.C., after his election. Why should we care about this historic trip?

As I’m discovering in perhaps too much detail, the trip was a real turning point for Lincoln and the country. It was grueling — 12 days long, with hundreds of speeches — and crowd turnout was unbelievable. He was transforming himself from a regional politician to the great president we know — tinkering with his inaugural every day — and this human contact reassured the public and strengthened his position. For millions of Americans, it was the only time they ever saw him. At the same time, there were terrifying moments when democracy seemed to be failing — crowds out of control, violence, etc. He was nearly killed on the last day of the trip. I’m surprised the trip hasn’t been studied in more detail before; it feels like the birth of the modern presidency in some ways.

You’ve studied presidential speeches — how do you rate Lincoln’s oratory on this trip?

Most of his speeches were simple greetings from the back of the train, but at least two were exceptional: his brilliant farewell to Springfield, and a powerful speech about human rights and the real meaning of America, delivered at Independence Hall in Philadelphia on Washington’s birthday. This was at a time, of course, when the meaning of America was up for grabs.